Glowing Edges Designs

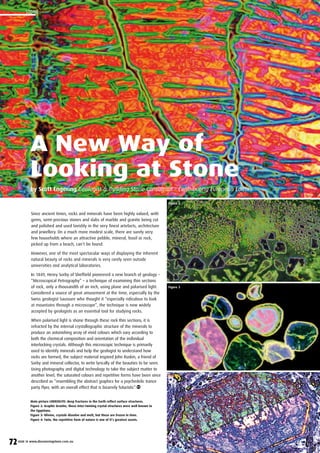

- 1. Since ancient times, rocks and minerals have been highly valued, with gems, semi-precious stones and slabs of marble and granite being cut and polished and used lavishly in the very finest artefacts, architecture and jewellery. On a much more modest scale, there are surely very few households where an attractive pebble, mineral, fossil or rock, picked up from a beach, can’t be found. However, one of the most spectacular ways of displaying the inherent natural beauty of rocks and minerals is very rarely seen outside universities and analytical laboratories. In 1849, Henry Sorby of Sheffield pioneered a new branch of geology – “Microscopical Petrography” – a technique of examining thin sections of rock, only a thousandth of an inch, using plane and polarised light. Considered a source of great amusement at the time, especially by the Swiss geologist Saussure who thought it “especially ridiculous to look at mountains through a microscope”, the technique is now widely accepted by geologists as an essential tool for studying rocks. When polarised light is shone through these rock thin sections, it is refracted by the internal crystallographic structure of the minerals to produce an astonishing array of vivid colours which vary according to both the chemical composition and orientation of the individual interlocking crystals. Although this microscopic technique is primarily used to identify minerals and help the geologist to understand how rocks are formed, the subject material inspired John Ruskin, a friend of Sorby and mineral collector, to write lyrically of the beauties to be seen. Using photography and digital technology to take the subject matter to another level, the saturated colours and repetitive forms have been since described as “resembling the abstract graphics for a psychedelic trance party flyer, with an overall effect that is bizarrely futuristic”. stonestone A New Way of Looking at Stone by Scott Engering Geologist & Building Stone Consultant - Contributing European Editor Main picture LHERZOLITE: deep fractures in the Earth reflect surface structures. Figure 2: Graphic Granite, these inter-twining crystal structures were well known to the Egyptians. Figure 3: Olivine, crystals dissolve and melt, but these are frozen in time. Figure 4: Twin, the repetitive form of nature is one of it’s greatest assets. Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 72issue 10 www.discoveringstone.com.au