045_6_fluids_advanced.ppt

- 2. Fluid and electrolyte balance is an extremely complicated thing.

- 3. Importance ÔÅÆ Need to make a decision regarding fluids in pretty much every hospitalized patient. ÔÅÆ Can be life-saving in certain conditions ÔÅÆ loss of body water, whether acute or chronic, can cause a range of problems from mild lightheadedness to convulsions, coma, and in some cases, death. ÔÅÆ Though fluid therapy can be a lifesaver, it's never innocuous, and can be very harmful.

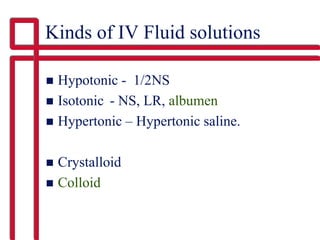

- 4. Kinds of IV Fluid solutions  Hypotonic - 1/2NS  Isotonic - NS, LR, albumen  Hypertonic – Hypertonic saline.  Crystalloid  Colloid

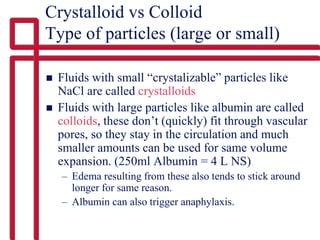

- 5. Crystalloid vs Colloid Type of particles (large or small)  Fluids with small “crystalizable” particles like NaCl are called crystalloids  Fluids with large particles like albumin are called colloids, these don’t (quickly) fit through vascular pores, so they stay in the circulation and much smaller amounts can be used for same volume expansion. (250ml Albumin = 4 L NS) – Edema resulting from these also tends to stick around longer for same reason. – Albumin can also trigger anaphylaxis.

- 6. There are two components to fluid therapy: ÔÅÆ Maintenance therapy replaces normal ongoing losses, and ÔÅÆ Replacement therapy corrects any existing water and electrolyte deficits.

- 7. Maintenance therapy  Maintenance therapy is usually undertaken when the individual is not expected to eat or drink normally for a longer time (eg, perioperatively or on a ventilator).  Big picture: Most people are “NPO” for 12 hours each day.  Patients who won’t eat for one to two weeks should be considered for parenteral or enteral nutrition.

- 8. Maintenance Requirements can be broken into water and electrolyte requirements:

- 9. Water —  Two liters of water per day are generally sufficient for adults;  Most of this minimum intake is usually derived from the water content of food and the water of oxidation, therefore  it has been estimated that only 500ml of water needs be imbibed given normal diet and no increased losses.  These sources of water are markedly reduced in patients who are not eating and so must be replaced by maintenance fluids.

- 10. ÔÅÆ water requirements increase with: fever, sweating, burns, tachypnea, surgical drains, polyuria, or ongoing significant gastrointestinal losses. ÔÅÆ For example, water requirements increase by 100 to 150 mL/day for each C degree of body temperature elevation.

- 11. Several formulas can be used to calculate maintenance fluid rates.

- 12. ÔÅÆ A comparison of formulas produces a wide variety of fluid recommendations: ÔÅÆ 2000 cc to 3378 cc for an obese woman who is 65 inches tall and weighs 248 pounds (112.6 kg) ÔÅÆ This is a reminder that fluid needs, no matter what formula is used, are at best an estimation.

- 13. 4/2/1 rule a.k.a Weight+40 ÔÅÆ I prefer the 4/2/1 rule (with a 120 mL/h limit) because it is the same as for pediatrics.

- 14. ÔÅÆ 4/2/1 rule 4 ml/kg/hr for first 10 kg (=40ml/hr) then 2 ml/kg/hr for next 10 kg (=20ml/hr) then 1 ml/kg/hr for any kgs over that This always gives 60ml/hr for first 20 kg then you add 1 ml/kg/hr for each kg over 20 kg This boils down to: Weight in kg + 40 = Maintenance IV rate/hour. For any person weighing more than 20kg

- 15. Maintenance IV rate: 4/2/1 rule -> Weight in kg + 40

- 16. What to put in the fluids ÔÅÆ

- 17. Start: D5 1/2NS+20 meq K @ Wt+40/hr ÔÅÆ a reasonable approach is to start 1/2 normal saline to which 20 meq of potassium chloride is added per liter. (1/2NS+20 K @ Wt+40/hr) ÔÅÆ Glucose in the form of dextrose (D5) can be added to provide some calories while the patient is NPO. ÔÅÆ The normal kidney can maintain sodium and potassium balance over a wide range of intakes. ÔÅÆ So,start: D5 1/2NS+20 meq K at a rate equal to their weight + 40ml/hr, but no greater than 120ml/hr. ÔÅÆ then adjust as needed, see next page.

- 18. Start D5 1/2NS+20 meq K, then adjust: ÔÅÆ If sodium falls, increase the concentration (eg, to NS) ÔÅÆ If sodium rises, decrease the concentration (eg, 1/4NS) ÔÅÆ If the plasma potassium starts to fall, add more potassium. ÔÅÆ If things are good, leave things alone.

- 19. Usually kidneys regulate well, but: Altered homeostasis in the hospital ÔÅÆ In the hospital, stress, pain, surgery can alter the normal mechanisms. ÔÅÆ Increased aldosterone, Increased ADH ÔÅÆ They generally make patients retain more water and salt, increase tendency for edema, and become hypokalemic.

- 24. Now onto Part 2 of the presentation:

- 25. Hypovolemia ÔÅÆ Hypovolemia or FVD is result of water & electrolyte loss ÔÅÆ Compensatory mechanisms include: Increased sympathetic nervous system stimulation with an increase in heart rate & cardiac contraction; thirst; plus release of ADH & aldosterone ÔÅÆ Severe case may result in hypovolemic shock or prolonged case may cause renal failure

- 26. Causes of FVD=hypovolemia: ÔÅÆ Gastrointestinal losses: N/V/D ÔÅÆ Renal losses: diuretics ÔÅÆ Skin or respiratory losses: burns ÔÅÆ Third-spacing: intestinal obstruction, pancreatitis

- 28. ÔÅÆ A variety of disorders lead to fluid losses that deplete the extracellular fluid . ÔÅÆ This can lead to a potentially fatal decrease in tissue perfusion. ÔÅÆ Fortunately, early diagnosis and treatment can restore normovolemia in almost all cases.

- 29. ÔÅÆ There is no easy formula for assessing the degree of hypovolemia. ÔÅÆ Hypovolemic Shock, the most severe form of hypolemia, is characterized by tachycardia, cold, clammy extremities, cyanosis, a low urine output (usually less than 15 mL/h), and agitation and confusion due to reduced cerebral blood flow. ÔÅÆ This needs rapid treatment with isotonic fluid boluses (1- 2L NS), and assessment and treatment of the underlying cause. ÔÅÆ But hypovolemia that is less severe and therefore well compensated is more difficult to accurately assess.

- 30. History for assessing hypovolemia ÔÅÆ The history can help to determine the presence and etiology of volume depletion. ÔÅÆ Weight loss! ÔÅÆ Early complaints include lassitude, easy fatiguability, thirst, muscle cramps, and postural dizziness. ÔÅÆ More severe fluid loss can lead to abdominal pain, chest pain, or lethargy and confusion due to ischemia of the mesenteric, coronary, or cerebral vascular beds, respectively. ÔÅÆ Nausea and malaise are the earliest findings of hyponatremia, and may be seen when the plasma sodium concentration falls below 125 to 130 meq/L. This may be followed by headache, lethargy, and obtundation ÔÅÆ Muscle weakness due to hypokalemia or hyperkalemia ÔÅÆ Polyuria and polydipsia due to hyperglycemia or severe hypokalemia ÔÅÆ Lethargy, confusion, seizures, and coma due to hyponatremia, hypernatremia, or hyperglycemia

- 31. Basic signs of hypovolemia ÔÅÆ Urine output, less than 30ml/hr ÔÅÆ Decreased BP, Increase pulse

- 32. Physical exam for assessing volume ÔÅÆ physical exam in general is not sensitive or specific ÔÅÆ acute weight loss; however, obtaining an accurate weight over time may be difficult ÔÅÆ decreased skin turgor - if you pinch it it stays put ÔÅÆ dry skin, particularly axilla ÔÅÆ dry mucus membranes ÔÅÆ low arterial blood pressure (or relative to patient's usual BP) ÔÅÆ orthostatic hypotension can occur with significant hypovolemia; but it is also common in euvolemic elderly subjects. ÔÅÆ decreased intensity of both the Korotkoff sounds (when the blood pressure is being measured with a sphygmomanometer) and the radial pulse ("thready") due to peripheral vasoconstriction. ÔÅÆ decreased Jugular Venous Pressure ÔÅÆ The normal venous pressure is 1 to 8 cmH2O, thus, a low value alone may be normal and does not establish the diagnosis of hypovolemia.

- 33. SIGNS & SYMPTOMS OF Fluid Volume Excess ÔÅÆ SOB & orthopnea ÔÅÆ Edema & weight gain ÔÅÆ Distended neck veins & tachycardia ÔÅÆ Increased blood pressure ÔÅÆ Crackles & wheezes ÔÅÆ pleural effusion

- 34. For the EBM aficionados out there. ÔÅÆ A JAMA 1999 systematic review of physical diagnosis of hypovolemia in adults ÔÅÆ CONCLUSIONS: A large postural pulse change (> or =30 beats/min) or severe postural dizziness is required to clinically diagnose hypovolemia due to blood loss, although these findings are often absent after moderate amounts of blood loss. In patients with vomiting, diarrhea, or decreased oral intake, few findings have proven utility, and clinicians should measure serum electrolytes, serum blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine levels when diagnostic certainty is required.

- 35. Which brings us to: Labnormalities seen with hypovolemia ÔÅÆ a variety of changes in urine and blood often accompany extracellular volume depletion. ÔÅÆ In addition to confirming the presence of volume depletion, these changes may provide important clues to the etiology.

- 36. BUN/Cr  BUN/Cr ratio normally around 10  Increase above 20 suggestive of “prerenal state”  (rise in BUN without rise in Cr called “prerenal azotemia.”)  This happens because with a low pressure head proximal to kidney, because urea (BUN) is resorbed somewhat, and creatinine is secreted somewhat as well

- 37. Hgb/Hct ÔÅÆ Acute loss of EC fluid volume causes hemoconcentration (if not due to blood loss) ÔÅÆ Acute gain of fluid will cause hemodilution of about 1g of hemoglobin (this happens very often.)

- 38. Plasma Na ÔÅÆ Decrease in Intravascular volume leads to greater avidity for Na (through aldosterone) AND water (through ADH), ÔÅÆ So overall, Plasma Na concentration tends to decrease from 140 when hypovolemia present.

- 39. Urine Na  Urine Na – goes down in prerenal states as body tries to hold onto water.  Getting a FENa helps correct for urine concentration.  Screwed up by lasix.  Calculator on PDA or medcalc.com

- 40. IV Modes of administration ÔÅÆ Peripheral IV ÔÅÆ PICC ÔÅÆ Central Line ÔÅÆ Intraosseous

- 41. IV Problem: Extravasation / “Infiltrated”  The most sensitive indicator of extravasated fluid or "infiltration" is to transilluminate the skin with a small penlight and look for the enhanced halo of light diffusion in the fluid filled area.  Checking flow of infusion does not tell you where the fluid is going

- 42.  That’s it folks.