Black Rot

- 1. Black Rot – Guignardia bidwelii The black rot fungus, Guignardia bidwelii, is a pathogen native to North America and can cause significant crop damage in Minnesota, under the right environmental conditions. Most Minnesota hardy varieties, Frontenac, Frontenac Gris and Marquette, are highly resistant while all common cultivars of V. vinifera are highly susceptible. Symptoms While black rot can infect all parts of the vine, the most significant losses are caused by berry infection. In warm humid climates, susceptible varieties can experience complete loss if the pathogen is left uncontrolled. Vegetative: Young leaves are susceptible to infection as they unfold, but become resistant once they mature. If infected, small, tan, circular spots appear in spring and early summer. They appear about two weeks after the initial infection. Within a few days small black fruiting bodies, pycnidia, will develop around the necrotic area. Lesions will appear on the petioles in spring and early summer. These lesions may expand and girdle the entire petiole killing the leaf. Infected young shoots will develop elongated black cankers throughout the growing season. If there are numerous cankers blighting of the tips can occur. Fruit: Berry infection is the most serious phase of black rot, possibly leading to significant economic losses. Berries are susceptible to infection immediately prior to bloom through four weeks after bloom. The first sign, easily missed, is the appearance of a small, whitish dot that is quickly surrounded by a reddish, brown ring. This ring can grow from 0.1cm to 2cm in one day. Within a few days the berry will start to dry out, loosing their spherical shape and becoming flat on the top (Figure 1). These berries will appear light or chocolate brown and quickly turn dark brown and develop black spores on the surface. Eventually, these infected berries will shrivel and become mummies, that serve as a secondary inoculum or overwintering structure for the pathogen. Disease Cycle Guidnardia bidwellii,the cause of black rot, overwinters in mummies on the vineyard floor or still hanging on the vine. In the spring, with a rain of 0.3mm or more, ascospores and conidia are released and dispersed by wind and water. This process can continue for up to eight hours after one rainfall. Research has shown that ascospores from mummies on the ground are discharged when shoot growth is 1-inch until three weeks after bloom. Mummies left on the vine will discharge ascospores and conidia throughout the growing season. Ascospores cause primary leaf and blossom infections. These infections occur, in the presence of free water, within six hours at 80o F. A longer wet period is required at cooler temperatures and no infection occurs when temperatures are over 90o F. Once leaves are

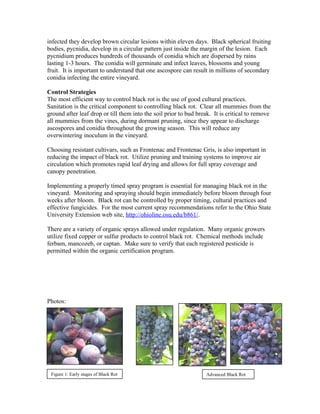

- 2. infected they develop brown circular lesions within eleven days. Black spherical fruiting bodies, pycnidia, develop in a circular pattern just inside the margin of the lesion. Each pycnidium produces hundreds of thousands of conidia which are dispersed by rains lasting 1-3 hours. The conidia will germinate and infect leaves, blossoms and young fruit. It is important to understand that one ascospore can result in millions of secondary conidia infecting the entire vineyard. Control Strategies The most efficient way to control black rot is the use of good cultural practices. Sanitation is the critical component to controlling black rot. Clear all mummies from the ground after leaf drop or till them into the soil prior to bud break. It is critical to remove all mummies from the vines, during dormant pruning, since they appear to discharge ascospores and conidia throughout the growing season. This will reduce any overwintering inoculum in the vineyard. Choosing resistant cultivars, such as Frontenac and Frontenac Gris, is also important in reducing the impact of black rot. Utilize pruning and training systems to improve air circulation which promotes rapid leaf drying and allows for full spray coverage and canopy penetration. Implementing a properly timed spray program is essential for managing black rot in the vineyard. Monitoring and spraying should begin immediately before bloom through four weeks after bloom. Black rot can be controlled by proper timing, cultural practices and effective fungicides. For the most current spray recommendations refer to the Ohio State University Extension web site, http://ohioline.osu.edu/b861/. There are a variety of organic sprays allowed under regulation. Many organic growers utilize fixed copper or sulfur products to control black rot. Chemical methods include ferbam, mancozeb, or captan. Make sure to verify that each registered pesticide is permitted within the organic certification program. Photos: Figure 1: Early stages of Black Rot Advanced Black Rot

- 3. Temperature Hours of Leaf Wetnesso C o F 7.0 45 No Infection 10.0 50 24 13.0 55 12 15.5 60 9 18.5 65 8 21.0 70 7 24.0 75 7 26.5 80 6 29.0 85 9 32.0 90 12 *R.A. Spotts, Ohio State University References: Wilcox, W. 2003, Grape Disease Identification sheet, Black Rot, Cornell University Cooperative Extension, http://www.nysipm.cornell.edu/factsheets/grapes/diseases/grape_br.pdf. Ellis, M. Doohan, D. Bordelon, B. Welty, C. Williams, R. Funt, R. Brown, M. 2004. Midwest Small Fruit Pest Management Handbook. The Ohio State University Extension. 123-125. http://ohioline.osu.edu/b861/. Broembsen, S. Pratt, P. accessed 2007, Black Rot of Grapes, Oklahoma Cooperrative Extension Service, http://pods.dasnr.okstate.edu/docushare/dsweb/Get/Document- 1011/F-7643web.pdf. Pearson, R. Goheen, A. 1998. Compendium of Grape Diseases, pg. 15-16. Hartman, J. Hershman, D. 1988, Black Rot of Grapes, College of Agriculture, University of Kentucky, http://www.ca.uky.edu/agc/pubs/ppa/ppa27/ppa27.htm. Rombough, L. 2002, The Grape Grower, A Guide to Organic Viticulture, Chelsea Green Publishing, pg. 90-91.