Anthrax.ppt

- 1. Anthrax Malignant Pustule, Malignant Edema, Woolsorters’ Disease, Ragpickers’ Disease, Maladi Charbon, Splenic Fever

- 2. Overview ? Organism ? History ? Epidemiology ? Transmission ? Disease in Animals ? Disease in Humans ? Prevention and Control Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 3. THE ORGANISM

- 4. The Organism ? Bacillus anthracis ? Large, gram-positive, non-motile rod ? Two forms – Vegetative, spore ? Over 1,200 strains ? Nearly worldwide distribution Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 5. The Spore ? Sporulation requires: – Poor nutrient conditions – Presence of oxygen ? Spores – Very resistant – Survive for decades – Taken up by host and germinate ? Lethal dose 2,500 to 55,000 spores Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 6. HISTORY

- 7. Sverdlovsk, Russia, 1979 ? 94 people sick – 64 died ? Soviets blamed contaminated meat ? Denied link to biological weapons ? 1992 – President Yeltsin admits outbreak related to military facility – Western scientists find victim clusters downwind from facility ? Caused by faulty exhaust filter Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 8. South Africa, 1978-1980 ? Anthrax used by Rhodesian and South African apartheid forces – Thousands of cattle died – 10,738 human cases – 182 known deaths – Black Tribal lands only Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 9. Tokyo, 1993 ? Aum Shinrikyo – Japanese religious cult – “Supreme truth” ? Attempt at biological terrorism – Released anthrax from office building – Vaccine strain used – No human injuries Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

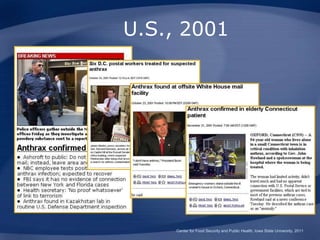

- 10. U.S., 2001 Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 11. U.S., 2001 ? 22 cases – 11 cutaneous – 11 inhalational; 5 deaths ? Cutaneous case – 7 month-old boy – Visited ABC newsroom – Open sore on arm – Anthrax positive Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 12. U.S., 2001 ? CDC survey of health officials – 7,000 reports regarding anthrax ? 1,050 led to lab testing – 1996-2000 ? Less than 180 anthrax inquiries ? Antimicrobial prophylaxis – Ciprofloxacin ? 5,343 prescriptions Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 13. TRANSMISSION

- 14. Human Transmission ? Cutaneous – Contact with infected tissues, wool, hide, soil – Biting flies ? Inhalational – Tanning hides, processing wool or bone ? Gastrointestinal – Undercooked meat Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 15. Human Transmission ? Tanneries ? Textile mills ? Wool sorters ? Bone processors ? Slaughterhouses ? Laboratory workers Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

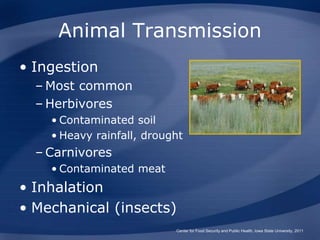

- 16. Animal Transmission ? Bacteria present in hemorrhagic exudate from mouth, nose, anus ? Oxygen exposure – Spores form – Soil contamination ? Sporulation does not occur in a closed carcass ? Spores viable for decades Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 17. Animal Transmission ? Ingestion – Most common – Herbivores ? Contaminated soil ? Heavy rainfall, drought – Carnivores ? Contaminated meat ? Inhalation ? Mechanical (insects) Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 18. EPIDEMIOLOGY

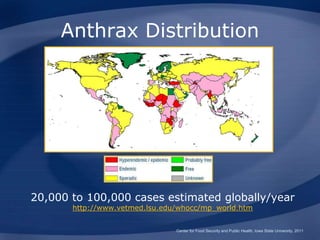

- 19. Anthrax Distribution 20,000 to 100,000 cases estimated globally/year http://www.vetmed.lsu.edu/whocc/mp_world.htm Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 20. Anthrax in the U.S. ? Cutaneous anthrax – Early 1900s: 200 cases annually – Late 1900s: 6 cases annually ? Inhalational anthrax – 20th century: 18 cases, 16 fatalities Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 21. Anthrax in the U.S. ? Alkaline soil ? “Anthrax weather” – Wet spring – Followed by hot, dry period ? Grass or vegetation damaged by flood-drought sequence ? Cattle primarily affected Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

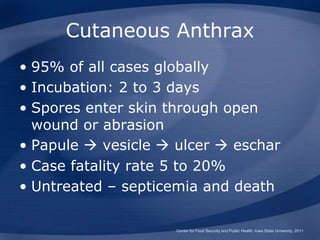

- 23. Cutaneous Anthrax ? 95% of all cases globally ? Incubation: 2 to 3 days ? Spores enter skin through open wound or abrasion ? Papule ? vesicle ? ulcer ? eschar ? Case fatality rate 5 to 20% ? Untreated – septicemia and death Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

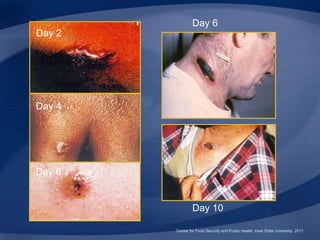

- 24. Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011 Day 2 Day 4 Day 6 Day 6 Day 10

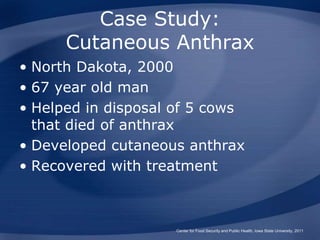

- 25. Case Study: Cutaneous Anthrax ? North Dakota, 2000 ? 67 year old man ? Helped in disposal of 5 cows that died of anthrax ? Developed cutaneous anthrax ? Recovered with treatment Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

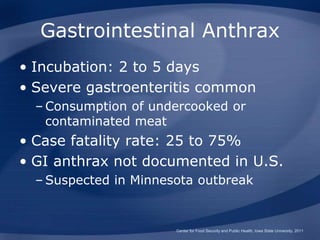

- 26. Gastrointestinal Anthrax ? Incubation: 2 to 5 days ? Severe gastroenteritis common – Consumption of undercooked or contaminated meat ? Case fatality rate: 25 to 75% ? GI anthrax not documented in U.S. – Suspected in Minnesota outbreak Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 27. Case Study: Gastrointestinal Anthrax ? Minnesota, 2000 ? Downer cow approved for slaughter by local veterinarian ? 5 family members ate meat – 2 developed GI signs ? 4 more cattle died ? B. anthracis isolated from farm but not from humans Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

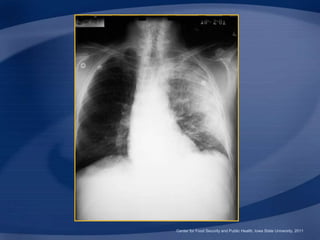

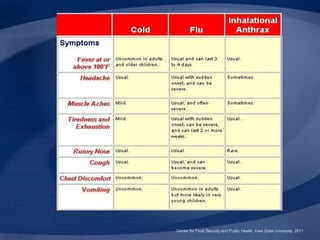

- 28. Inhalational Anthrax ? Incubation: 1 to 7 days ? Initial phase – Nonspecific (mild fever, malaise) ? Second phase – Severe respiratory distress – Dyspnea, stridor, cyanosis, mediastinal widening, death in 24 to 36 hours ? Case fatality: 75 to 90% (untreated) Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 29. Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

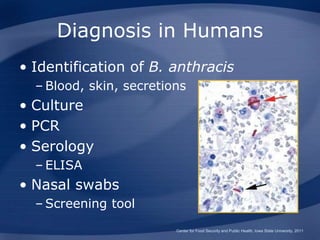

- 30. Diagnosis in Humans ? Identification of B. anthracis – Blood, skin, secretions ? Culture ? PCR ? Serology – ELISA ? Nasal swabs – Screening tool Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 31. Treatment ? Penicillin – Most natural strains susceptible ? Additional antibiotic options – Ciprofloxacin ? Treatment of choice in 2001 ? No strains known to be resistant – Doxycycline ? Course of treatment: 60 days Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 32. Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 33. Prevention and Control ? Humans protected by preventing disease in animals ?Veterinary supervision ?Trade restrictions ? Improved industry standards ? Safety practices in laboratories ? Post-exposure antibiotic prophylaxis Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

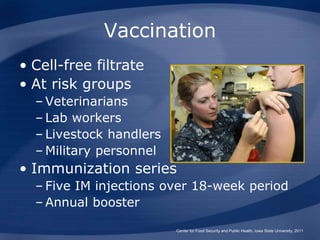

- 34. Vaccination ? Cell-free filtrate ? At risk groups – Veterinarians – Lab workers – Livestock handlers – Military personnel ? Immunization series – Five IM injections over 18-week period – Annual booster Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

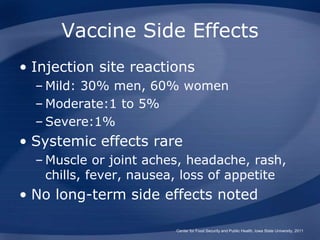

- 35. Vaccine Side Effects ? Injection site reactions – Mild: 30% men, 60% women – Moderate:1 to 5% – Severe:1% ? Systemic effects rare – Muscle or joint aches, headache, rash, chills, fever, nausea, loss of appetite ? No long-term side effects noted Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 37. Clinical Signs ? Many species affected – Ruminants at greatest risk ? Three forms – Peracute ? Ruminants (cattle, sheep, goats, antelope) – Acute ? Ruminants and equine – Subacute-chronic ? Swine, dogs, cats Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 38. Ruminants ? Peracute – Sudden death ? Acute – Tremors, dyspnea – Bloody discharge from body orifices ? Chronic (rare) – Pharyngeal and lingual edema – Death from asphyxiation Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 39. Differential Diagnosis (Ruminants) ? Blackleg ? Botulism ? Poisoning – Plants, heavy metal, snake bite ? Lightning strike ? Peracute babesiosis Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 40. Equine ? Acute – Fever, anorexia, colic, bloody diarrhea – Swelling in neck ? Dyspnea ? Death from asphyxiation – Death in 1 to 3 days ? Insect bite – Hot, painful swelling at site Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011 Photo from WHO

- 41. Pigs ? Acute disease uncommon ? Subacute to chronic – Localized swelling of throat ? Dyspnea ? Asphyxiation – Anorexia – Vomiting, diarrhea Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 42. Carnivores ? Relatively resistant – Ingestion of contaminated raw meat ? Subacute to chronic – Fever, anorexia, weakness – Necrosis and edema of upper GI tract – Lymphadenopathy and edema of head and neck – Death ? Due to asphyxiation, toxemia, septicemia Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 43. Diagnosis and Treatment ? Necropsy not advised! ? Do not open carcass! ? Samples of peripheral blood needed – Cover collection site with disinfectant soaked bandage to prevent leakage ? Treatment – Penicillin, tetracyclines ? Reportable disease Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

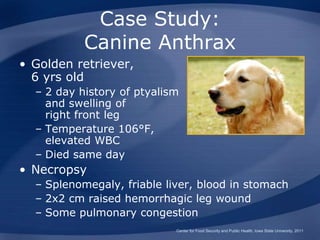

- 44. Case Study: Canine Anthrax ? Golden retriever, 6 yrs old – 2 day history of ptyalism and swelling of right front leg – Temperature 106°F, elevated WBC – Died same day ? Necropsy – Splenomegaly, friable liver, blood in stomach – 2x2 cm raised hemorrhagic leg wound – Some pulmonary congestion Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 45. Case Study: Canine Anthrax ? Source of exposure in question – Residential area – 1 mile from livestock – No livestock deaths in area – Dove hunt on freshly plowed field 6 days prior to onset ? Signs consistent with ingestion but cutaneous exposure not ruled out Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2008

- 46. Vaccination ? Livestock in endemic areas ? Sterne strain – Live encapsulated spore vaccine ? No U.S. vaccine for pets – Used in other countries – Adjuvant may cause reactions ? Working dogs may be at risk Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 47. Animals and Anthrax ? Anthrax should always be high on differential list when: – High mortality rates observed in herbivores – Sudden deaths with unclotted blood from orifices occur – Localized edema observed ? Especially neck of pigs or dogs Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 49. Prevention and Control ? Report to authorities ? Quarantine the area ? Do not open carcass ? Minimize contact ? Wear protective clothing – Latex gloves, face mask Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 50. Prevention and Control ? Local regulations determine carcass disposal options – Incineration – Deep burial ? Decontaminate soil ? Remove organic material and disinfect structures Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 51. Prevention and Control ? Isolate sick animals ? Discourage scavengers ? Use insect control or repellants ? Prophylactic antibiotics ? Vaccination – In endemic areas – Endangered animals Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 52. Disinfection ? Spores resistant to heat, sunlight, drying and many disinfectants ? Disinfectants – Formaldehyde (5%) – Glutaraldehyde (2%) – Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) (10%) – Bleach ? Gas or heat sterilization ? Gamma radiation Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 53. Disinfection ? Preliminary disinfection – 10% formaldehyde – 4% glutaraldehyde (pH 8.0-8.5) ? Cleaning – Hot water, scrubbing, protective clothing ? Final disinfection: one of the following – 10% formaldehyde – 4% glutaraldehyde (pH 8.0-8.5) – 3% hydrogen peroxide, – 1% peracetic acid Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 54. Biological Terrorism: Estimated Effects ? 50 kg of spores – Urban area of 5 million – Estimated impact ? 250,000 cases of anthrax ? 100,000 deaths ? 100 kg of spores – Upwind of Wash D.C. – Estimated impact ? 130,000 to 3 million deaths Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 55. Additional Resources ? World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) – www.oie.int ? U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) – www.aphis.usda.gov ? Center for Food Security and Public Health – www.cfsph.iastate.edu ? USAHA Foreign Animal Diseases (“The Gray Book”) – www.aphis.usda.gov/emergency_response/do wnloads/nahems/fad.pdf Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

- 56. Acknowledgments Development of this presentation was made possible through grants provided to the Center for Food Security and Public Health at Iowa State University, College of Veterinary Medicine from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Iowa Homeland Security and Emergency Management Division, and the Multi-State Partnership for Security in Agriculture. Authors: Radford Davis, DVM, MPH, DACVPM; Jamie Snow, DVM; Katie Steneroden, DVM; Anna Rovid Spickler, DVM, PhD; Reviewers: Dipa Brahmbhatt, VMD; Katie Spaulding, BS; Glenda Dvorak, DVM, MPH, DACVPM; Kerry Leedom Larson, DVM, MPH, PhD Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, 2011

![ibp_final_ppts_3[1].pptxggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg...](https://cdn.slidesharecdn.com/ss_thumbnails/ibpfinalppts31-250301115347-400d9677-thumbnail.jpg?width=560&fit=bounds)

![DEEPTI presentation[1].pptx on research thesis](https://cdn.slidesharecdn.com/ss_thumbnails/deeptipresentation1-250308175835-5ed4ee51-thumbnail.jpg?width=560&fit=bounds)