Competent Validation for Subsidiarity

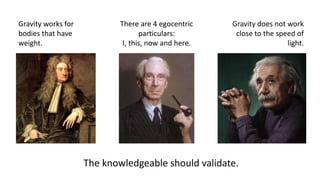

- 1. The knowledgeable should validate. Gravity works for bodies that have weight. There are 4 egocentric particulars: I, this, now and here. Gravity does not work close to the speed of light.

- 2. conceptualisation model implementation The New Frontier of Experience Innovation validating the applicability of relevant knowledge validating the relevance of consistent knowledge validating the consistency of accessible knowledge this herenow

Editor's Notes

- Competent Validation for Subsidiarity: We Validate where We Know Today I am going to talk to you about one of the toughest problems scholars face ŌĆō yet, interestingly, this is something that practitioners engage in all the time: it is the problem of validation. Let me start with an example. When Isaac Newton figured out gravity in the 17th century, he first realised something that we call a rule; that is, that bodies attract each other. For this he only needed an apple to hit him on his head. In time, he identified what we can call a ŌĆśscope of validityŌĆÖ; this means that he figured out that gravity works for bodies that have weight. A rule together with an identified scope of validity makes a law. To be really precise, we should emphasise that Newton identified ŌĆśa scope of validityŌĆÖ, so one well-defined area in which the rule works. From knowing one scope of validity, we do not know whether there are any other scopes in which the rule is valid. However, at this time, we cannot talk about a theory of gravity. For this we had to wait some 250 years for Einstein. He figured out also under what conditions NewtonŌĆÖs rule does not work: if the speeds are great, close to the speed of light, NewtonŌĆÖs rule is invalid. At speeds significantly lower than the speed of light, gravity works as Newton specified. Only since this point we can talk about NewtonŌĆÖs theory of gravity. This means that Einstein added something very significant to NewtonŌĆÖs understanding of gravity. However, today I donŌĆÖt want to talk about science; I want to talk about practitioners. And practitioners are not interested in creating a theory; in other words, they are OK with a Newton-level knowledge of gravity, they donŌĆÖt need the Einsteinian addition. Or, as I will emphasise later on, it is about practitioners who are also thinkers. Perhaps it is not so difficult to understand the notion of validity through this example and as practitioners constantly engage in validating, you may be wandering why I claim that it is (one of) the toughest problems scholars engage in ŌĆō there must be something I have left out isnŌĆÖt it? Of course I have. I have not told you about the reference point yet. The reference point is provided by Bertrand Russell; it is what he calls egocentric particulars; there are 4 of these: I, this, now and here. Russell emphasises two characteristics of the egocentric particulars: they are centrally important and semantically mysterious. This essentially means that we cannot get rid of them, we cannot think in any other way than through the egocentric particulars and yet, they seem to be extremely difficult to adequately define ŌĆō but today we only need an intuitive understanding. This part is easy: everyone understands I, this, now and here. Let me take a brief detour, so that I can get the first egocentric particular sorted out. Many of you will be familiar with Thomas KuhnŌĆÖs ŌĆśStructure of Scientific RevolutionsŌĆÖ. What perhaps fewer are familiar with, is that a few years after the third edition of the book, Kuhn wrote a postscript to the ŌĆśStructuresŌĆÖ. It is in this postscript where he mentions that when Columbus suggested that the Earth is like a ball, it was received with a great deal of disbelief. People found it impossible as that would mean that people in China would hang upside-down. Today many of us understand that the root cause of this disbelief is the misunderstanding of the nature of up-and-down, which essentially means misunderstanding the nature of gravity. What I am trying to get at is that we, meaning the average person with a schooled mind, have a much better understanding of gravity than the contemporaries of Columbus, and therefore we can validate what Columbus suggested. What we can learn from Newton, Einstein and Columbus is that the knowledgeable should validate. This means two things. The first is that we arrived at the concept of subsidiarity in a different way: the principle of subsidiarity in this formulation means that the knowledgeable should validate. The second learning point so far is that we can identify the first egocentric particular, the ŌĆśIŌĆÖ, as the knowledgeable validator.

- Now I want to tell you about how we managed to achieve an understanding of validity through the remaining three of RussellŌĆÖs egocentric particulars. The first aspect of validity relates to the ŌĆśthisŌĆÖ particular, and we call it consistency. The second relates to ŌĆśnowŌĆÖ, and we call it relevance. The third relates to ŌĆśhereŌĆÖ and we call it applicability. The starting point of the validation is a particular knowledge we have access to (we cannot possibly validate something we cannot access), and we choose it for validation ŌĆō it is ŌĆśthisŌĆÖ knowledge. Nothing else participates in the validation of consistency, only ŌĆśthisŌĆÖ knowledge, and ŌĆśIŌĆÖ the knowledgeable validator. What the knowledgeable validator does when validating the consistency of ŌĆśthisŌĆÖ knowledge is that (s)he tries to make sense of it. This means, for instance, that the knowledgeable validator is interested in whether there are internal contradictions in ŌĆśthisŌĆÖ knowledge. For simplicity we can say that ŌĆśthisŌĆÖ knowledge should be contradiction-free, but this is not entirely correct, some knowledgeable validators may be able and willing to accept some degree of contradictions. This is what happened to me with Pol├ĪnyiŌĆÖs Personal Knowledge ŌĆō but this is a story for a different occasion. What is important, is that the outcome of validating the consistency is a conceptualisation. Only knowledge accepted as consistent can enter the validation of relevance, which means looking into whether the consistent knowledge corresponds to the phenomenon that the knowledgeable validator is interested in ŌĆśnowŌĆÖ. Those who are well-versed in a scientific discipline, will easily identify relevance with construct validity, and they will not be wrong. In terms of the outcome, we could say that validating the relevance takes us from a conceptualisation to a model. Knowledge that is found relevant, can enter the validation of applicability ŌĆśhereŌĆÖ. ŌĆśHereŌĆÖ refers to the context in which the knowledgeable validator intends to use the relevant knowledge. Context ŌĆśhereŌĆÖ is particularly a point where practitioners often deal with a greater degree of complexity than what academics typically try to achieve, there is an organisational culture, local culture, any number of stakeholders, etc. What happens in terms of the outcomes during the validation of applicability, is that we get from a model to an implementation. It is important to understand that consistency, relevance, and applicability are all necessary for a successful implementation. What happens if knowledge is applied outside the scope of validity? Firstly, we have no idea whether it works or what it does. Secondly, we lose orientation. We end up as Charles tells us about getting directions with reference to DukeŌĆÖs pub: take the last right before the DukeŌĆÖs ŌĆō the reference point is outside, so you can only figure it out once you have missed it. Now let me offer you an example to bring the problem of validity closer to you. New accessible knowledge for this example is described by CK Prahalad and Venkat Ramaswamy; it is called co-creation. Zolt├Īn Baracskai and I have identified this new knowledge and we were able to access it, we were turning it upside and down, inside and out for months, and we found it consistent. It made sense to us. Thus it became a conceptualisation. Therefore we invited a few knowledgeable colleagues to examine the relevance of this consistent knowledge. In a two-day workshop this group of knowledgeable validators ŌĆśapprovedŌĆÖ the relevance, and so it became a model. Finally, we started the validation of applicability through recruiting prospective doctoral students for the programme ŌĆō but I have to admit that the validation of the applicability will be an ongoing process as the students are progressing, new ones are recruited, some graduate, etc. I have chosen this example because I see it as consistent, it is relevant for this audience, and it is applicable in your lives, as you are practitioners as well as thinkers. Of course, it is not how we arrived at this understanding. If you promise not to tell anyone, I will admit that this understanding is not the result of a scholarly inquiry or of our quest into the realm of research philosophy. To be sure, we were doing that for many years as well. However, the three potatoes crystallised from a many-year engagement with various organisations. Once we started to explore the notion of validity with reference to practitioners, we have realised that we have been repeatedly going through this process of validation over and over again, every single time when we brought some new knowledge into the life of an organisation. Each one of our students will also have to go through these three aspects of validation not only in order to achieve an implemented knowledge, but primarily in order to become better practitioners than they were before getting back to the school one more time. So now, instead of Q&A, I would like to invite everyone to reflect on the validity of what I have offered in my presentation. Deal? No? Okay, you can take this as a homework, and now you can ask questions.