COMPLETE NOTES ON DECECChapter-02_1.pptx

Download as PPTX, PDF0 likes7 views

COMPLETE NOTES ON DECECChapter-02_1.pptx

1 of 21

Download to read offline

Recommended

Measurement erros

Measurement erroschakrimvn

╠²

This document discusses types of errors in measurement. There are three main types of errors: gross errors due to mistakes, systematic errors that cause consistent deviations, and random errors from unpredictable factors. Accuracy refers to the deviation from the true value, while precision refers to the consistency of repeated measurements. Calibration compares instruments to standards to determine accuracy and uncertainty. Error analysis evaluates experimental data to identify errors and validate results.Quality assurance errors

Quality assurance errorsAliRaza1767

╠²

This document discusses types of errors that can occur in measurement. It describes absolute and relative errors, and how errors can be expressed. There are various sources of error, including the instrument, workpiece, person, and environment. Errors are classified as systematic/controllable or random. Systematic errors include calibration errors, environmental errors, stylus pressure errors, and avoidable errors. Random errors cause fluctuations that are positive or negative.Errorsandmistakesinchaining 170810071200

Errorsandmistakesinchaining 170810071200Mir Zafarullah

╠²

The document discusses various types of errors and mistakes that can occur when measuring distances using a chain or tape. It describes two types of errors - cumulative errors, which accumulate and affect accuracy, and compensating errors, which cancel out. Examples of each are provided. Mistakes are defined as errors from carelessness rather than instruments, and don't follow rules. The document also outlines corrections that must be applied to measurements for factors like slope, temperature, tension, and sag.Static terms in measurement

Static terms in measurementChetan Mahatme

╠²

The document discusses key concepts related to measurement including range, span, accuracy, error, calibration, hysteresis, drift, and sensitivity. Range refers to the minimum and maximum values an instrument can measure. Span is the difference between the upper and lower range values. Accuracy depends on factors like the instrument's intrinsic properties and environmental conditions. Calibration involves comparing an instrument's readings to standards to determine corrections needed to conform to accepted values. Hysteresis and drift refer to unwanted changes in readings unrelated to the input being measured. Sensitivity is the ratio of output response to input.Assignment on errors

Assignment on errorsIndian Institute of Technology Delhi

╠²

This document discusses various types of errors that can occur when making measurements with instruments. It defines error as the difference between the expected and measured values. There are two main types of errors - static errors, which occur due to limitations in the instrument, and dynamic errors, which occur when the instrument cannot keep up with rapid changes. Static errors include gross errors from human mistakes, systematic errors due to instrument defects, and random errors from small unpredictable factors. The document provides examples of different sources of systematic errors like instrumentation errors, environmental influences, and observational errors. It also discusses methods for estimating random errors and other error types like limiting, parallax, and quantization errors.Errors in measurement

Errors in measurementPrabhaMaheswariM

╠²

Errors in measurement can be categorized as static, systematic, or random. Static errors represent the difference between the true and measured values. Systematic errors are due to issues with instruments, environments, or observations. Random errors occur due to sudden changes and can only be reduced by taking multiple readings. There are various types of systematic errors such as instrumental errors from shortcomings, misuse, or loading effects, and environmental errors from temperature, pressure, or other external conditions. Statistical analysis methods like finding the average, deviations, standard deviation, and variance can help determine the most probable value from a set of measurements.Measurement and error

Measurement and errorcyberns_

╠²

This document provides an overview of the DEE1012 measurement course. It outlines the course learning outcomes, which are to apply measurement principles and solve problems using measuring operations and theorems. The document then details several topics that will be covered in the course, including the measurement process, elements of a measurement system, types of errors, measurement terminology, characteristics of measurement, and standards used in measurement. Examples are provided to illustrate key concepts. References are listed at the end.Errors in Measuring Instruments.ppt

Errors in Measuring Instruments.ppttadi1padma

╠²

There are three main types of errors in measurement instruments:

1. Gross errors are due to human mistakes like misreading or incorrectly recording data. They can be large errors and are avoided by taking multiple readings carefully.

2. Systematic errors are predictable and include instrumental errors from defects, environmental errors from external conditions, and observational errors from parallax or incorrect conversions.

3. Random errors are unpredictable and caused by unknown external factors affecting the measurement. They are also called residual errors.Measurements and-sources-of-errors1

Measurements and-sources-of-errors1Vikash Kumar

╠²

There are two categories of measurement errors: systematic errors, which are consistent and repeatable, and random errors, which produce inconsistent scatter in measurements. Systematic errors can be caused by calibration issues, loading effects, defective equipment, or human biases. Random errors result from unpredictable fluctuations and limit measurement precision. Sources of error also include zero offset, nonlinearity, sensitivity problems, finite resolution, environmental factors, and issues with reading techniques, instrument loading, supports, dirt, vibrations, metallurgy, contacts, deflection, looseness, gauge wear, location, contact quality, and stylus impression. Careful consideration of error sources is important for obtaining accurate measurements.EM unit 1 part 5.pdf

EM unit 1 part 5.pdftadi1padma

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur when measuring instruments are used. There are three main types of errors: gross errors, which are usually due to human mistakes; systematic errors, which include instrumental errors from device limitations, environmental errors from external conditions, and observational errors from parallax or incorrect readings; and random errors, which are due to unknown factors affecting the measurement. Specific examples of errors in permanent magnet moving-coil meters and moving-iron instruments are also described, such as temperature effects changing resistance or hysteresis causing inaccurate readings. Methods to minimize various errors, such as using materials with stable properties or shielding instruments, are also mentioned.Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptx

Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptxChinna Chadayan

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur in measurement. There are five main types of errors:

1) Gross errors are faults made by the person using the instrument, such as incorrect readings or recordings.

2) Systematic errors are due to problems with the instrument itself, environmental factors, or observational errors made by the observer.

3) Random errors remain after gross and systematic errors have been reduced and are due to unknown causes. Taking multiple readings and analyzing them statistically can help minimize random errors.

4) Absolute error is the difference between the expected and measured values.

5) Relative error expresses the error as a percentage of the real measurement.Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptx

Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptxChinna Chadayan

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur in measurement. There are five main types of errors:

1) Gross errors are faults made by the person using the instrument, such as incorrect readings or recordings.

2) Systematic errors are due to problems with the instrument itself, environmental factors, or observational errors made by the observer.

3) Random errors remain after gross and systematic errors have been reduced and are due to unknown causes. Taking multiple readings and analyzing them statistically can help minimize random errors.

4) Absolute error is the difference between the expected and measured values.

5) Relative error expresses the error as a percentage of the real measurement.Module 1 mmm 17 e46b

Module 1 mmm 17 e46bD N ROOPA

╠²

This document provides an overview of mechanical measurements and metrology. It discusses key concepts like accuracy, precision, types of errors in measurement, calibration, standards, and classification of measuring instruments. The objectives of metrology are outlined as ensuring measuring instruments are adequate and maintained through calibration. Factors affecting measurement accuracy are explored including the standard, workpiece, instrument, operator, and environment. Common methods of measurement and classification of instruments are also summarized.ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS MEASUREMENT

ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS MEASUREMENT Dinesh Sharma

╠²

This document discusses measurement techniques and instruments. It covers the basic components, classifications, functions, and errors of measurement instruments. The key points are:

- Measurement instruments have components for deflection, control, and damping of the pointer. Deflection indicates the measured quantity, control opposes deflection, and damping reduces oscillations.

- Instruments can be classified as analog or digital, absolute or secondary. Accuracy depends on design, materials, and errors like systematic, random, and environmental errors.

- Measurements involve comparing an unknown quantity to a standard and expressing the result numerically. Direct comparison is used when possible, otherwise indirect methods are used. Proper standards and methods are required for meaningful results.Measurements and-sources-of-errors1

Measurements and-sources-of-errors1Vikash Kumar

╠²

This document discusses measurement and sources of error. It defines measurement as determining size, quantity, or degree of something. Primary measurements include length, angle, and curvature. Measurements have standard units like meters and kilograms. Methods of measurement are direct comparison to standards or indirect comparison. Measuring instruments include tools for angles, lengths, surfaces, and deviations. Errors are differences between true and measured values. There are systematic errors that are consistent and random errors that are inconsistent and cause scatter. Sources of error include calibration, loading, environment, reading, and vibrations.class 18.08.2020.pptx

class 18.08.2020.pptxGOBINATH KANDASAMY

╠²

The document discusses different types of errors that can occur when making measurements. It describes three main categories of errors: gross errors due to human mistakes, systematic errors due to issues with instruments, and random errors from unknown external factors. It provides examples of errors from instrument construction and calibration, environmental conditions, observer techniques, and more. The document emphasizes the importance of understanding error sources in order to reduce errors and improve measurement accuracy.Experimental Stress Analysis 2 Mark Q_A.docx

Experimental Stress Analysis 2 Mark Q_A.docxharishm164877

╠²

This document discusses various topics related to experimental stress analysis including measurement, instrumentation, photoelasticity, and non-destructive testing. It defines key terms, describes methods and principles, and discusses advantages and limitations. Specifically, it discusses the basic principles of measurement, requirements for accurate measurement, types of errors, static and dynamic characteristics of instruments, principles of photoelasticity, properties of photoelastic materials, and advantages of non-destructive testing techniques like radiography and brittle coating methods.Lecture 2 errors and uncertainty

Lecture 2 errors and uncertaintySarhat Adam

╠²

Errors and Uncertainty are parts of surveying. These slides start first by defining scale and measurements, then show how to determine the uncertainty in measurements. For making these slides I used some books as well; Surveying_Engineering Surveying 6th edition, Surveying Problem Solving, & Surevying_Elemntary Surveying an introduction to Geomatics_Paul R. Wolf. 1.2

1.2Paula Mills

╠²

This document discusses measurement and uncertainties in the SI system of units. It describes the fundamental SI units of length, mass, time, electric current, temperature, and amount of substance. Derived quantities are those involving two or more fundamental units, with derived units having specific names and symbols. Standards for the metre, kilogram and second are defined. Conversion between units is explained. Errors can be random or systematic. Random errors decrease with multiple measurements but systematic errors do not. Accuracy refers to closeness to the accepted value while precision refers to the agreement between measurements. The limit of reading and degree of uncertainty are defined. Methods to reduce random uncertainties include taking multiple readings and calculating the mean and absolute error. Absolute, fractional and percentage uncertainties are146056297 cc-modul

146056297 cc-modulhomeworkping3

╠²

homework help,online homework help,online tutors,online tutoring,research paper help,do my homework,

https://www.homeworkping.com/1.2

1.2Paula Mills

╠²

This document discusses measurement and uncertainties in physics. It introduces standard SI units which are used for measurement in most countries. Fundamental quantities like length, time and mass cannot be measured in simpler terms and form the basis of other derived units. Accuracy refers to how close a measurement is to the accepted value, while precision refers to the agreement between multiple measurements. Random and systematic errors can affect measurements and need to be accounted for using techniques like taking multiple readings and estimating uncertainties. Graphs are useful for analyzing experimental data and determining relationships between variables.Unit-1 Measurement and Error.pdf

Unit-1 Measurement and Error.pdfdivyapriya balasubramani

╠²

1. Computational adjustment is a process that makes measured survey values more accurate before using them to determine point positions. It involves distributing random errors in measurements to conform to certain geometric conditions.

2. Key concepts in measurement and error include direct and indirect measurements, systematic and random errors, and statistical analysis of errors using measures like the mean, median, standard deviation, and histogram. Redundant observations allow detection of random errors.

3. Probability concepts like population, sample, measures of central tendency, variation, and relative standing are important for understanding measurement reliability and adjusting observations statistically. Degrees of freedom refer to redundant observations.1-170114040648.pdf

1-170114040648.pdfDuddu Rajesh

╠²

Classification of sensors includes:

- Active vs passive (input excitation required)

- Null vs deflection type (balancing vs deflection)

- Analog vs digital output (continuous vs discrete)

Static characteristics include:

- Span and range (measurement limits)

- Accuracy and precision (closeness to true value and repeatability)

- Resolution and sensitivity (smallest detectable change)

Sources of error include:

- Instrument errors from construction, calibration, loading

- Environmental errors from temperature, pressure, humidity

- Observational errors from reading, recording, calculationUnit1 Measurement and Tech

Unit1 Measurement and TechHira Rizvi

╠²

This document provides a checklist of learning outcomes for general physics. It covers physical quantities and units, including the SI base units. It also covers measurement techniques and the distinction between systematic and random errors. Students should be able to measure various physical quantities using tools like rulers, vernier calipers, micrometers, and understand the concepts of uncertainty, accuracy, and precision in measurements. They should also be able to distinguish between scalar and vector quantities and perform vector operations.Electrical Measurement & Instruments

Electrical Measurement & InstrumentsChandan Singh

╠²

Electrical and electronic measuring equipment. Ammeter. Capacitance meter. Distortionmeter. Electricity meter. Frequency counter. Galvanometer. LCR meter. Microwave power meter.15. Smart Cities Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia.pdf

15. Smart Cities Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia.pdfNgocThang9

╠²

Smart Cities Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New UtopiaWireless-Charger presentation for seminar .pdf

Wireless-Charger presentation for seminar .pdfAbhinandanMishra30

╠²

Wireless technology used in chargerMore Related Content

Similar to COMPLETE NOTES ON DECECChapter-02_1.pptx (20)

Errors in Measuring Instruments.ppt

Errors in Measuring Instruments.ppttadi1padma

╠²

There are three main types of errors in measurement instruments:

1. Gross errors are due to human mistakes like misreading or incorrectly recording data. They can be large errors and are avoided by taking multiple readings carefully.

2. Systematic errors are predictable and include instrumental errors from defects, environmental errors from external conditions, and observational errors from parallax or incorrect conversions.

3. Random errors are unpredictable and caused by unknown external factors affecting the measurement. They are also called residual errors.Measurements and-sources-of-errors1

Measurements and-sources-of-errors1Vikash Kumar

╠²

There are two categories of measurement errors: systematic errors, which are consistent and repeatable, and random errors, which produce inconsistent scatter in measurements. Systematic errors can be caused by calibration issues, loading effects, defective equipment, or human biases. Random errors result from unpredictable fluctuations and limit measurement precision. Sources of error also include zero offset, nonlinearity, sensitivity problems, finite resolution, environmental factors, and issues with reading techniques, instrument loading, supports, dirt, vibrations, metallurgy, contacts, deflection, looseness, gauge wear, location, contact quality, and stylus impression. Careful consideration of error sources is important for obtaining accurate measurements.EM unit 1 part 5.pdf

EM unit 1 part 5.pdftadi1padma

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur when measuring instruments are used. There are three main types of errors: gross errors, which are usually due to human mistakes; systematic errors, which include instrumental errors from device limitations, environmental errors from external conditions, and observational errors from parallax or incorrect readings; and random errors, which are due to unknown factors affecting the measurement. Specific examples of errors in permanent magnet moving-coil meters and moving-iron instruments are also described, such as temperature effects changing resistance or hysteresis causing inaccurate readings. Methods to minimize various errors, such as using materials with stable properties or shielding instruments, are also mentioned.Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptx

Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptxChinna Chadayan

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur in measurement. There are five main types of errors:

1) Gross errors are faults made by the person using the instrument, such as incorrect readings or recordings.

2) Systematic errors are due to problems with the instrument itself, environmental factors, or observational errors made by the observer.

3) Random errors remain after gross and systematic errors have been reduced and are due to unknown causes. Taking multiple readings and analyzing them statistically can help minimize random errors.

4) Absolute error is the difference between the expected and measured values.

5) Relative error expresses the error as a percentage of the real measurement.Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptx

Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptxChinna Chadayan

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur in measurement. There are five main types of errors:

1) Gross errors are faults made by the person using the instrument, such as incorrect readings or recordings.

2) Systematic errors are due to problems with the instrument itself, environmental factors, or observational errors made by the observer.

3) Random errors remain after gross and systematic errors have been reduced and are due to unknown causes. Taking multiple readings and analyzing them statistically can help minimize random errors.

4) Absolute error is the difference between the expected and measured values.

5) Relative error expresses the error as a percentage of the real measurement.Module 1 mmm 17 e46b

Module 1 mmm 17 e46bD N ROOPA

╠²

This document provides an overview of mechanical measurements and metrology. It discusses key concepts like accuracy, precision, types of errors in measurement, calibration, standards, and classification of measuring instruments. The objectives of metrology are outlined as ensuring measuring instruments are adequate and maintained through calibration. Factors affecting measurement accuracy are explored including the standard, workpiece, instrument, operator, and environment. Common methods of measurement and classification of instruments are also summarized.ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS MEASUREMENT

ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS MEASUREMENT Dinesh Sharma

╠²

This document discusses measurement techniques and instruments. It covers the basic components, classifications, functions, and errors of measurement instruments. The key points are:

- Measurement instruments have components for deflection, control, and damping of the pointer. Deflection indicates the measured quantity, control opposes deflection, and damping reduces oscillations.

- Instruments can be classified as analog or digital, absolute or secondary. Accuracy depends on design, materials, and errors like systematic, random, and environmental errors.

- Measurements involve comparing an unknown quantity to a standard and expressing the result numerically. Direct comparison is used when possible, otherwise indirect methods are used. Proper standards and methods are required for meaningful results.Measurements and-sources-of-errors1

Measurements and-sources-of-errors1Vikash Kumar

╠²

This document discusses measurement and sources of error. It defines measurement as determining size, quantity, or degree of something. Primary measurements include length, angle, and curvature. Measurements have standard units like meters and kilograms. Methods of measurement are direct comparison to standards or indirect comparison. Measuring instruments include tools for angles, lengths, surfaces, and deviations. Errors are differences between true and measured values. There are systematic errors that are consistent and random errors that are inconsistent and cause scatter. Sources of error include calibration, loading, environment, reading, and vibrations.class 18.08.2020.pptx

class 18.08.2020.pptxGOBINATH KANDASAMY

╠²

The document discusses different types of errors that can occur when making measurements. It describes three main categories of errors: gross errors due to human mistakes, systematic errors due to issues with instruments, and random errors from unknown external factors. It provides examples of errors from instrument construction and calibration, environmental conditions, observer techniques, and more. The document emphasizes the importance of understanding error sources in order to reduce errors and improve measurement accuracy.Experimental Stress Analysis 2 Mark Q_A.docx

Experimental Stress Analysis 2 Mark Q_A.docxharishm164877

╠²

This document discusses various topics related to experimental stress analysis including measurement, instrumentation, photoelasticity, and non-destructive testing. It defines key terms, describes methods and principles, and discusses advantages and limitations. Specifically, it discusses the basic principles of measurement, requirements for accurate measurement, types of errors, static and dynamic characteristics of instruments, principles of photoelasticity, properties of photoelastic materials, and advantages of non-destructive testing techniques like radiography and brittle coating methods.Lecture 2 errors and uncertainty

Lecture 2 errors and uncertaintySarhat Adam

╠²

Errors and Uncertainty are parts of surveying. These slides start first by defining scale and measurements, then show how to determine the uncertainty in measurements. For making these slides I used some books as well; Surveying_Engineering Surveying 6th edition, Surveying Problem Solving, & Surevying_Elemntary Surveying an introduction to Geomatics_Paul R. Wolf. 1.2

1.2Paula Mills

╠²

This document discusses measurement and uncertainties in the SI system of units. It describes the fundamental SI units of length, mass, time, electric current, temperature, and amount of substance. Derived quantities are those involving two or more fundamental units, with derived units having specific names and symbols. Standards for the metre, kilogram and second are defined. Conversion between units is explained. Errors can be random or systematic. Random errors decrease with multiple measurements but systematic errors do not. Accuracy refers to closeness to the accepted value while precision refers to the agreement between measurements. The limit of reading and degree of uncertainty are defined. Methods to reduce random uncertainties include taking multiple readings and calculating the mean and absolute error. Absolute, fractional and percentage uncertainties are146056297 cc-modul

146056297 cc-modulhomeworkping3

╠²

homework help,online homework help,online tutors,online tutoring,research paper help,do my homework,

https://www.homeworkping.com/1.2

1.2Paula Mills

╠²

This document discusses measurement and uncertainties in physics. It introduces standard SI units which are used for measurement in most countries. Fundamental quantities like length, time and mass cannot be measured in simpler terms and form the basis of other derived units. Accuracy refers to how close a measurement is to the accepted value, while precision refers to the agreement between multiple measurements. Random and systematic errors can affect measurements and need to be accounted for using techniques like taking multiple readings and estimating uncertainties. Graphs are useful for analyzing experimental data and determining relationships between variables.Unit-1 Measurement and Error.pdf

Unit-1 Measurement and Error.pdfdivyapriya balasubramani

╠²

1. Computational adjustment is a process that makes measured survey values more accurate before using them to determine point positions. It involves distributing random errors in measurements to conform to certain geometric conditions.

2. Key concepts in measurement and error include direct and indirect measurements, systematic and random errors, and statistical analysis of errors using measures like the mean, median, standard deviation, and histogram. Redundant observations allow detection of random errors.

3. Probability concepts like population, sample, measures of central tendency, variation, and relative standing are important for understanding measurement reliability and adjusting observations statistically. Degrees of freedom refer to redundant observations.1-170114040648.pdf

1-170114040648.pdfDuddu Rajesh

╠²

Classification of sensors includes:

- Active vs passive (input excitation required)

- Null vs deflection type (balancing vs deflection)

- Analog vs digital output (continuous vs discrete)

Static characteristics include:

- Span and range (measurement limits)

- Accuracy and precision (closeness to true value and repeatability)

- Resolution and sensitivity (smallest detectable change)

Sources of error include:

- Instrument errors from construction, calibration, loading

- Environmental errors from temperature, pressure, humidity

- Observational errors from reading, recording, calculationUnit1 Measurement and Tech

Unit1 Measurement and TechHira Rizvi

╠²

This document provides a checklist of learning outcomes for general physics. It covers physical quantities and units, including the SI base units. It also covers measurement techniques and the distinction between systematic and random errors. Students should be able to measure various physical quantities using tools like rulers, vernier calipers, micrometers, and understand the concepts of uncertainty, accuracy, and precision in measurements. They should also be able to distinguish between scalar and vector quantities and perform vector operations.Electrical Measurement & Instruments

Electrical Measurement & InstrumentsChandan Singh

╠²

Electrical and electronic measuring equipment. Ammeter. Capacitance meter. Distortionmeter. Electricity meter. Frequency counter. Galvanometer. LCR meter. Microwave power meter.Recently uploaded (20)

15. Smart Cities Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia.pdf

15. Smart Cities Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia.pdfNgocThang9

╠²

Smart Cities Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New UtopiaWireless-Charger presentation for seminar .pdf

Wireless-Charger presentation for seminar .pdfAbhinandanMishra30

╠²

Wireless technology used in chargerIntegration of Additive Manufacturing (AM) with IoT : A Smart Manufacturing A...

Integration of Additive Manufacturing (AM) with IoT : A Smart Manufacturing A...ASHISHDESAI85

╠²

Combining 3D printing with Internet of Things (IoT) enables the creation of smart, connected, and customizable objects that can monitor, control, and optimize their performance, potentially revolutionizing various industries. oT-enabled 3D printers can use sensors to monitor the quality of prints during the printing process. If any defects or deviations from the desired specifications are detected, the printer can adjust its parameters in real time to ensure that the final product meets the required standards.How to Build a Maze Solving Robot Using Arduino

How to Build a Maze Solving Robot Using ArduinoCircuitDigest

╠²

Learn how to make an Arduino-powered robot that can navigate mazes on its own using IR sensors and "Hand on the wall" algorithm.

This step-by-step guide will show you how to build your own maze-solving robot using Arduino UNO, three IR sensors, and basic components that you can easily find in your local electronics shop.Mathematics behind machine learning INT255 INT255__Unit 3__PPT-1.pptx

Mathematics behind machine learning INT255 INT255__Unit 3__PPT-1.pptxppkmurthy2006

╠²

Mathematics behind machine learning INT255 Lessons learned when managing MySQL in the Cloud

Lessons learned when managing MySQL in the CloudIgor Donchovski

╠²

Managing MySQL in the cloud introduces a new set of challenges compared to traditional on-premises setups, from ensuring optimal performance to handling unexpected outages. In this article, we delve into covering topics such as performance tuning, cost-effective scalability, and maintaining high availability. We also explore the importance of monitoring, automation, and best practices for disaster recovery to minimize downtime.Lecture -3 Cold water supply system.pptx

Lecture -3 Cold water supply system.pptxrabiaatif2

╠²

The presentation on Cold Water Supply explored the fundamental principles of water distribution in buildings. It covered sources of cold water, including municipal supply, wells, and rainwater harvesting. Key components such as storage tanks, pipes, valves, and pumps were discussed for efficient water delivery. Various distribution systems, including direct and indirect supply methods, were analyzed for residential and commercial applications. The presentation emphasized water quality, pressure regulation, and contamination prevention. Common issues like pipe corrosion, leaks, and pressure drops were addressed along with maintenance strategies. Diagrams and case studies illustrated system layouts and best practices for optimal performance.Syntax Directed Definitions Synthesized Attributes and Inherited Attributes

Syntax Directed Definitions Synthesized Attributes and Inherited AttributesGunjalSanjay

╠²

Syntax Directed Definitions

Env and Water Supply Engg._Dr. Hasan.pdf

Env and Water Supply Engg._Dr. Hasan.pdfMahmudHasan747870

╠²

Core course, namely Environment and Water Supply Engineering. Full lecture notes are in book format for the BSc in Civil Engineering program. decarbonization steel industry rev1.pptx

decarbonization steel industry rev1.pptxgonzalezolabarriaped

╠²

Webinar Decarbonization steel industryUS Patented ReGenX Generator, ReGen-X Quatum Motor EV Regenerative Accelerati...

US Patented ReGenX Generator, ReGen-X Quatum Motor EV Regenerative Accelerati...Thane Heins NOBEL PRIZE WINNING ENERGY RESEARCHER

╠²

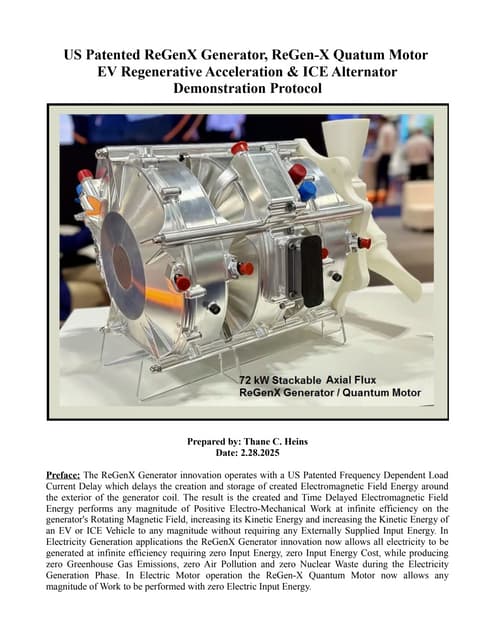

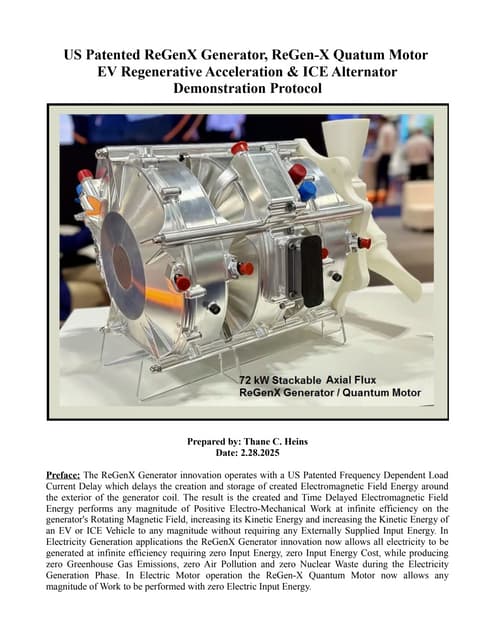

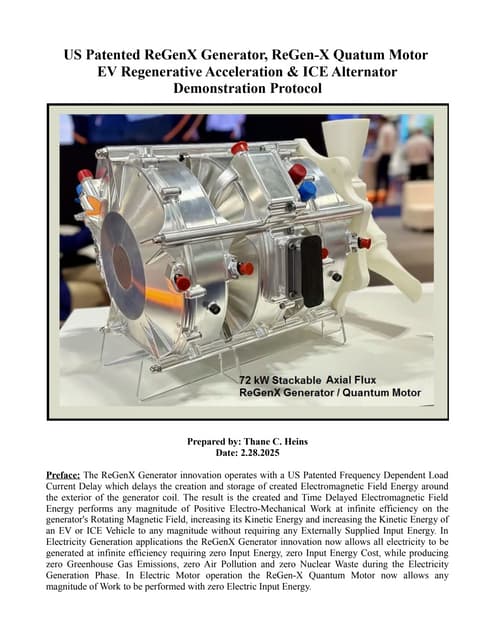

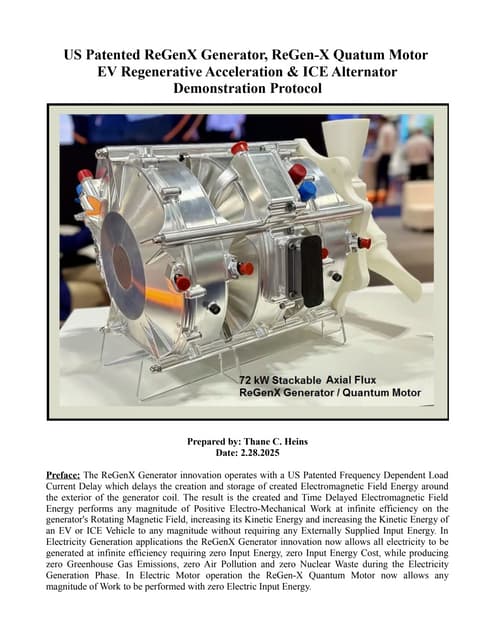

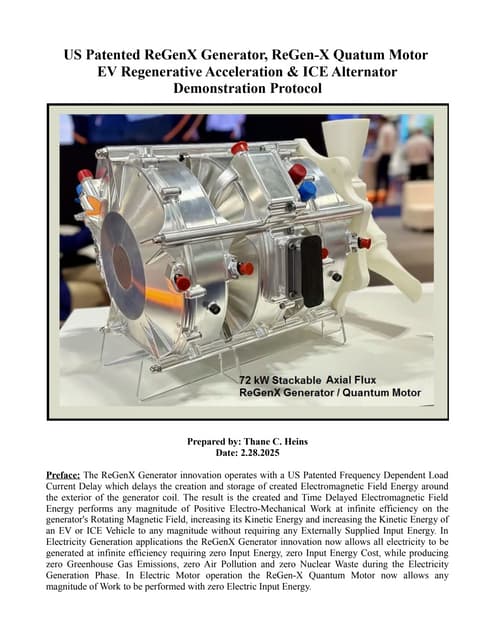

Preface: The ReGenX Generator innovation operates with a US Patented Frequency Dependent Load Current Delay which delays the creation and storage of created Electromagnetic Field Energy around the exterior of the generator coil. The result is the created and Time Delayed Electromagnetic Field Energy performs any magnitude of Positive Electro-Mechanical Work at infinite efficiency on the generator's Rotating Magnetic Field, increasing its Kinetic Energy and increasing the Kinetic Energy of an EV or ICE Vehicle to any magnitude without requiring any Externally Supplied Input Energy. In Electricity Generation applications the ReGenX Generator innovation now allows all electricity to be generated at infinite efficiency requiring zero Input Energy, zero Input Energy Cost, while producing zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions, zero Air Pollution and zero Nuclear Waste during the Electricity Generation Phase. In Electric Motor operation the ReGen-X Quantum Motor now allows any magnitude of Work to be performed with zero Electric Input Energy.

Demonstration Protocol: The demonstration protocol involves three prototypes;

1. Protytpe #1, demonstrates the ReGenX Generator's Load Current Time Delay when compared to the instantaneous Load Current Sine Wave for a Conventional Generator Coil.

2. In the Conventional Faraday Generator operation the created Electromagnetic Field Energy performs Negative Work at infinite efficiency and it reduces the Kinetic Energy of the system.

3. The Magnitude of the Negative Work / System Kinetic Energy Reduction (in Joules) is equal to the Magnitude of the created Electromagnetic Field Energy (also in Joules).

4. When the Conventional Faraday Generator is placed On-Load, Negative Work is performed and the speed of the system decreases according to Lenz's Law of Induction.

5. In order to maintain the System Speed and the Electric Power magnitude to the Loads, additional Input Power must be supplied to the Prime Mover and additional Mechanical Input Power must be supplied to the Generator's Drive Shaft.

6. For example, if 100 Watts of Electric Power is delivered to the Load by the Faraday Generator, an additional >100 Watts of Mechanical Input Power must be supplied to the Generator's Drive Shaft by the Prime Mover.

7. If 1 MW of Electric Power is delivered to the Load by the Faraday Generator, an additional >1 MW Watts of Mechanical Input Power must be supplied to the Generator's Drive Shaft by the Prime Mover.

8. Generally speaking the ratio is 2 Watts of Mechanical Input Power to every 1 Watt of Electric Output Power generated.

9. The increase in Drive Shaft Mechanical Input Power is provided by the Prime Mover and the Input Energy Source which powers the Prime Mover.

10. In the Heins ReGenX Generator operation the created and Time Delayed Electromagnetic Field Energy performs Positive Work at infinite efficiency and it increases the Kinetic Energy of the system.Sachpazis: Foundation Analysis and Design: Single Piles

Sachpazis: Foundation Analysis and Design: Single PilesDr.Costas Sachpazis

╠²

Žü. ╬ÜŽÄŽāŽä╬▒Žé ╬Ż╬▒ŽćŽĆ╬¼╬Č╬ĘŽé: Foundation Analysis and Design: Single Piles

Welcome to this comprehensive presentation on "Foundation Analysis and Design," focusing on Single PilesŌĆöStatic Capacity, Lateral Loads, and Pile/Pole Buckling. This presentation will explore the fundamental concepts, equations, and practical considerations for designing and analyzing pile foundations.

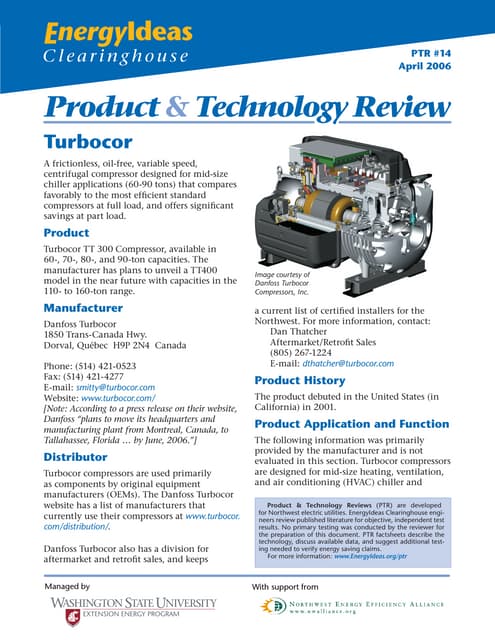

We'll examine different pile types, their characteristics, load transfer mechanisms, and the complex interactions between piles and surrounding soil. Throughout this presentation, we'll highlight key equations and methodologies for calculating pile capacities under various conditions.Turbocor Product and Technology Review.pdf

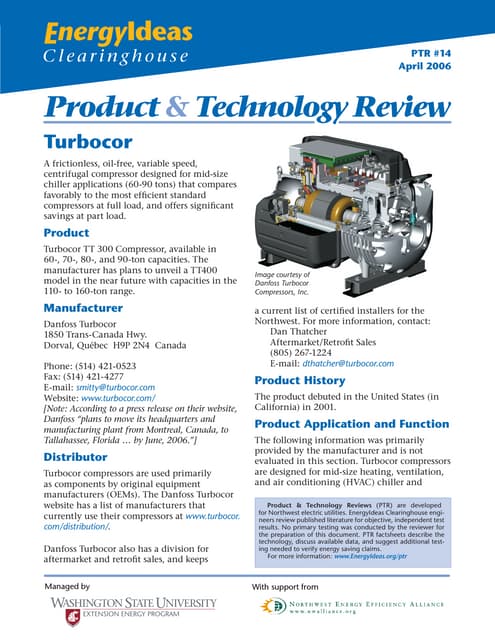

Turbocor Product and Technology Review.pdfTotok Sulistiyanto

╠²

High Efficiency Chiller System in HVACUS Patented ReGenX Generator, ReGen-X Quatum Motor EV Regenerative Accelerati...

US Patented ReGenX Generator, ReGen-X Quatum Motor EV Regenerative Accelerati...Thane Heins NOBEL PRIZE WINNING ENERGY RESEARCHER

╠²

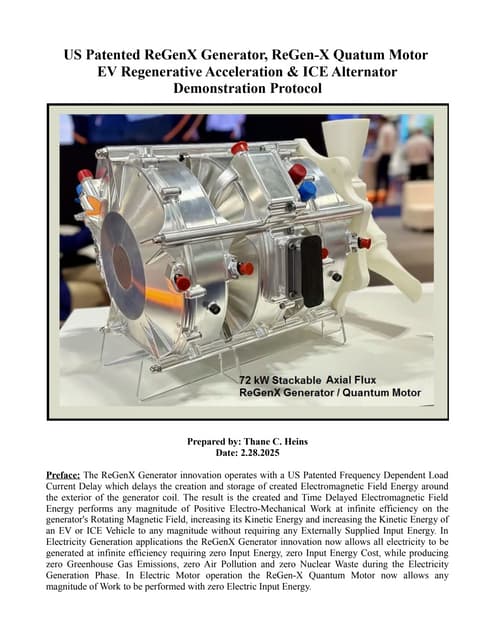

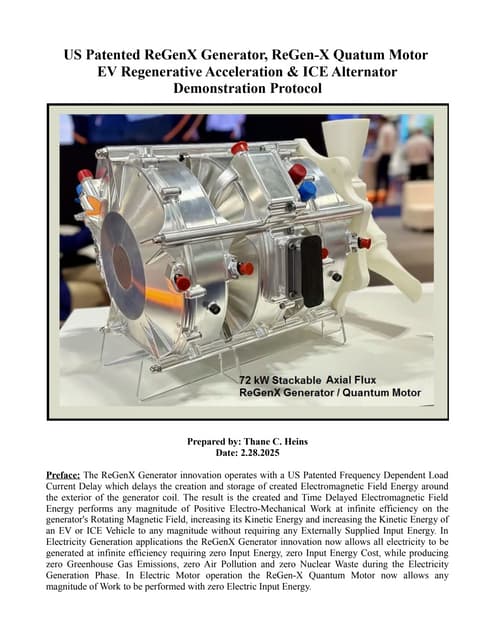

Preface: The ReGenX Generator innovation operates with a US Patented Frequency Dependent Load

Current Delay which delays the creation and storage of created Electromagnetic Field Energy around

the exterior of the generator coil. The result is the created and Time Delayed Electromagnetic Field

Energy performs any magnitude of Positive Electro-Mechanical Work at infinite efficiency on the

generator's Rotating Magnetic Field, increasing its Kinetic Energy and increasing the Kinetic Energy of

an EV or ICE Vehicle to any magnitude without requiring any Externally Supplied Input Energy. In

Electricity Generation applications the ReGenX Generator innovation now allows all electricity to be

generated at infinite efficiency requiring zero Input Energy, zero Input Energy Cost, while producing

zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions, zero Air Pollution and zero Nuclear Waste during the Electricity

Generation Phase. In Electric Motor operation the ReGen-X Quantum Motor now allows any

magnitude of Work to be performed with zero Electric Input Energy.

Demonstration Protocol: The demonstration protocol involves three prototypes;

1. Protytpe #1, demonstrates the ReGenX Generator's Load Current Time Delay when compared

to the instantaneous Load Current Sine Wave for a Conventional Generator Coil.

2. In the Conventional Faraday Generator operation the created Electromagnetic Field Energy

performs Negative Work at infinite efficiency and it reduces the Kinetic Energy of the system.

3. The Magnitude of the Negative Work / System Kinetic Energy Reduction (in Joules) is equal to

the Magnitude of the created Electromagnetic Field Energy (also in Joules).

4. When the Conventional Faraday Generator is placed On-Load, Negative Work is performed and

the speed of the system decreases according to Lenz's Law of Induction.

5. In order to maintain the System Speed and the Electric Power magnitude to the Loads,

additional Input Power must be supplied to the Prime Mover and additional Mechanical Input

Power must be supplied to the Generator's Drive Shaft.

6. For example, if 100 Watts of Electric Power is delivered to the Load by the Faraday Generator,

an additional >100 Watts of Mechanical Input Power must be supplied to the Generator's Drive

Shaft by the Prime Mover.

7. If 1 MW of Electric Power is delivered to the Load by the Faraday Generator, an additional >1

MW Watts of Mechanical Input Power must be supplied to the Generator's Drive Shaft by the

Prime Mover.

8. Generally speaking the ratio is 2 Watts of Mechanical Input Power to every 1 Watt of Electric

Output Power generated.

9. The increase in Drive Shaft Mechanical Input Power is provided by the Prime Mover and the

Input Energy Source which powers the Prime Mover.

10. In the Heins ReGenX Generator operation the created and Time Delayed Electromagnetic Field

Energy performs Positive Work at infinite efficiency and it increases the Kinetic Energy of the

system.

AI, Tariffs and Supply Chains in Knowledge Graphs

AI, Tariffs and Supply Chains in Knowledge GraphsMax De Marzi

╠²

How tarrifs, supply chains and knowledge graphs combine.US Patented ReGenX Generator, ReGen-X Quatum Motor EV Regenerative Accelerati...

US Patented ReGenX Generator, ReGen-X Quatum Motor EV Regenerative Accelerati...Thane Heins NOBEL PRIZE WINNING ENERGY RESEARCHER

╠²

US Patented ReGenX Generator, ReGen-X Quatum Motor EV Regenerative Accelerati...

US Patented ReGenX Generator, ReGen-X Quatum Motor EV Regenerative Accelerati...Thane Heins NOBEL PRIZE WINNING ENERGY RESEARCHER

╠²

COMPLETE NOTES ON DECECChapter-02_1.pptx

- 1. Chapter-02 Measurements & Errors 2.1 Units, System of Units, Significant figures and rounding off numbers 2.2 Errors, Sources & Types 2.3 Precision, Accuracy & permissible error

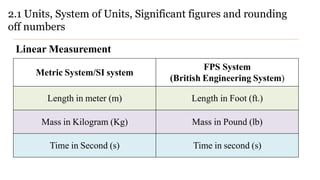

- 2. 2.1 Units, System of Units, Significant figures and rounding off numbers Linear Measurement Metric System/SI system FPS System (British Engineering System) Length in meter (m) Length in Foot (ft.) Mass in Kilogram (Kg) Mass in Pound (lb) Time in Second (s) Time in second (s)

- 3. Angular Measurement: 1. Sexagesimal System (English system) ’ü▒ degrees, minutes, seconds 2. Centesimal System (French System) ’ü▒ grade, minutes, seconds ’é¦ 1 right angle = 100 grades ’é¦ 1 grades = 100 minutes ’é¦ 1 minutes = 100 seconds 3. Circular System (radians) Aradian is an angle subtended at the center of a circle by an arc whose length is equal to the radius. radians=degreeŌłŚ(PI/180) 90┬░ = ŽĆ/2 rad, 180┬░ = ŽĆ rad, 360┬░ = 2ŽĆ rad 2.1 Units, System of Units, Significant figures and rounding off numbers

- 4. 2.1 Units, System of Units, Significant figures and rounding off numbers Ropani Aana 16 Bigha Paisa 4 64 Kattha 20 Daam 4 16 256 Dhur 20 400 1.99 m2 7.95 m2 31.80 m2 508.74 m2 16.93 m2 338.63 m2 6772.63 m2 21.39 ft2 85.56 ft2 342.25 ft2 5476 ft2 182.25 ft2 3645 ft2 72900 ft2

- 5. 2.2 Errors, Sources & Types Error in an observation is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and the true value of that quantity. Error = Measured Value ŌĆō True Value Types of Errors A. Mistakes/Blunders B. Systematic errors C. Random errors/Accidental error

- 6. 2.2 Errors, Sources & Types A. Mistakes/Blunders ’é¦ Mistakes or blunders are unpredictable human mistakes caused due to carelessness, misunderstanding, confusion or poor judgment. ’é¦ Mistakes can be avoided by alertness, common sense and good judgment. Common types of Mistakes/Blunders are: oTransposition of numbers oNeglecting to level an instrument oMisplacing decimal point oSighting on incorrect control point

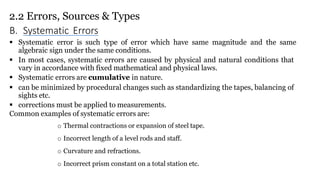

- 7. 2.2 Errors, Sources & Types B. Systematic Errors ’é¦ Systematic error is such type of error which have same magnitude and the same algebraic sign under the same conditions. ’é¦ In most cases, systematic errors are caused by physical and natural conditions that vary in accordance with fixed mathematical and physical laws. ’é¦ Systematic errors are cumulative in nature. ’é¦ can be minimized by procedural changes such as standardizing the tapes, balancing of sights etc. ’é¦ corrections must be applied to measurements. Common examples of systematic errors are: o Thermal contractions or expansion of steel tape. o Incorrect length of a level rods and staff. o Curvature and refractions. o Incorrect prism constant on a total station etc.

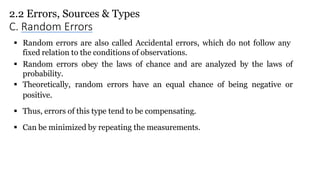

- 8. 2.2 Errors, Sources & Types C. Random Errors ’é¦ Random errors are also called Accidental errors, which do not follow any fixed relation to the conditions of observations. ’é¦ Random errors obey the laws of chance and are analyzed by the laws of probability. ’é¦ Theoretically, random errors have an equal chance of being negative or positive. ’é¦ Thus, errors of this type tend to be compensating. ’é¦ Can be minimized by repeating the measurements.

- 9. 2.2 Errors, Sources & Types Sources of Errors a) Personal Errors ’é¦ Personal errors are caused by physical limitations and observing habits of an observer. They can be either systematic or random. b) Instrumental Errors ’é¦ Instrumental errors are caused by the imperfections in the design, construction, and adjustment of instruments and other accessories. ’é¦ Most instrumental errors are eliminated by using proper procedures such as observing angles direct and reverse, balancing foresights and back sights and repeating measurements. ’é¦ Minimized by periodically checking and adjusting (or calibrating) instruments and other equipment. Example: ’é¦ Wrong calibration in the tape or staff. ’é¦ Wrong calibration of EDM ’é¦ Bubble out problem in level, theodolite

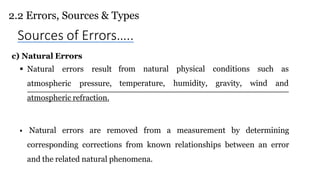

- 10. 2.2 Errors, Sources & Types Sources of ErrorsŌĆ”.. from natural temperature, physical humidity, conditions gravity, wind such as and c) Natural Errors ’é¦ Natural errors result atmospheric pressure, atmospheric refraction. ’é¦ Natural errors are removed from a measurement by determining corresponding corrections from known relationships between an error and the related natural phenomena.

- 11. 2.2 Errors, Sources & Types COMMON MISTAKES IN CHAINING/TAPPING: ’ü▒ Displacement of the arrows. ’ü▒ Failure to observe the zero point of the tape. ’ü▒ Reading from the wrong end of the chain/tape. ’ü▒ Reading numbers wrongly/ Reading wrong meter marks. ’ü▒ Wrong recording in the field book. ’ü▒ Calling numbers wrongly.

- 12. 2.3 Precision, Accuracy & permissible error Accuracy: ’é¦ Accuracy is defined as ŌĆśThe degree of closeness with the ŌĆśstandard valueŌĆÖ and essentially refers to how close a measurement is to its agreed value. ’é¦ Degree of perfection obtained in the measurement. Precision: ’é¦ Precision refers to closeness of two or more measurements to each other. ’é¦ Precision indicates the level of detail, refinement, or granularity in the measurement.

- 13. 2.3 Precision, Accuracy & Permissible error

- 14. 2.3 Precision, Accuracy & permissible error Discrepancy: is the difference between two measured values of the same quantity. ’é¦ Discrepancy may be small, yet the errors can be large if both the observed values contain almost equal error. Error: in an observation is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and the true value of that quantity. Error = Measured Value ŌĆō True Value

- 15. 2.3 Precision, Accuracy & permissible error Q. In angular measurement of a triangle ABC, the internal angles are found ’āÉA= 60’é░ 30’éó, ’āÉB= 45’é░ 20’éó, ’āÉC= 75’é░ 30’éó. Calculate the error in measurement and accuracy of the work.

- 16. 2.3 Precision, Accuracy & permissible error Q. In angular measurement of a triangle ABC, the internal angles are found ’āÉA= 60’é░ 30’éó, ’āÉB= 45’é░ 20’éó, ’āÉC= 75’é░ 30’éó. Calculate the error in measurement and accuracy of the work.

- 17. 2.3 Precision, Accuracy & permissible error

- 18. 2.3 Precision, Accuracy & permissible error

- 19. 2.3 Precision, Accuracy & permissible error Permissible error: ŌĆó Refers to the acceptable level of error or tolerance allowed in the measurement of survey data. ŌĆó The specific permissible error varies depending on the type of survey, the purpose of the survey, and the accuracy requirements of the project. ŌĆó Different surveying applications may have different permissible error standards.

- 20. Assignments Make a proper note of this Chapter in your note copy

- 21. THANK YOU