Exhibition in Twentieth-Century American Medicine

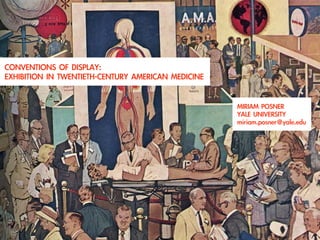

- 1. Conventions of Display: Exhibition in Twentieth-Century American Medicine Miriam Posner ŌĆó Yale University ŌĆó miriam.posner@yale.edu

- 2. Washington Post, June 7, 1937

- 3. Freeman (second from left) demonstrating at an exhibit

- 4. Freeman (second from left) demonstrating at an exhibit

- 5. Stevan Dohanos, At the Convention, 1960 (detail)

- 6. Photograph from Hull and Jones, Scienti’¼üc Exhibits (1961)

- 7. 1899: the exhibit begins Journal of the American Medical Association, June 17, 1899

- 8. 1899 ŌĆō 1945: the exhibit expands Demonstrating an exhibit, 1935

- 9. Illustration from Hull and Jones, Scienti’¼üc Exhibits (1961)

- 10. Illustration from Hull and Jones, Scienti’¼üc Exhibits (1961)

- 11. Demonstrating an exhibit, 1935

- 12. Floor plan for 1925 AMA Scienti’¼üc Exhibit

- 13. Floor plan for 1925 AMA Scienti’¼üc Exhibit

- 14. 1945 ŌĆō 1965: the exhibitŌĆÖs baroque period Demonstrating an exhibit, 1955 AMAŌĆÖs Scienti’¼üc Exhibit, ca. 1960

- 15. Demonstrating an exhibit, 1955

- 16. An audiovisual exhibit, 1962

- 17. A live demonstration, 1962

- 19. 1965 ŌĆō 1980: the exhibit in decline

- 20. A young scientist and his poster, 2006

- 21. 2006 exhibit award winners at the New York State Society of Anesthesiologists convention

- 22. A PowerPoint template for medical presentations

- 23. 1. A lively, interactive pedagogical and probative culture An interactive exhibit, 1962

- 24. 2. Medicine and showmanship The technical exhibit, 1935

- 25. Floor plan, 1925 AMA Scienti’¼üc Exhibit

- 26. Illustration from Hull and Jones, Scienti’¼üc Exhibits (1961)

- 27. 3. Palpability and virtuality A fresh tissue pathology exhibit, 1962

- 28. 4. Opening the body to display Filming an operation, 1953

Editor's Notes

- My boyfriend happens to be a science person and I always thought it was sort of cute when he went to conferences, because he’d get a poster ready for the poster session. I thought it was so funny and sort of poignant that real scientists would stand around in a convention hall next to their posters. I didn’t really think much about it, but it did cause a bell to ring a little while later. I was doing some research on Walter Freeman, the neurologist who pioneered lobotomy, and I was interested to read about one of Freeman’s earliest successes.

- It seems that, in 1937, Freeman decided to demonstrate the salutary effects of lobotomy by exhibiting two caged monkeys at an American Medical Association meeting. One monkey had a lobotomy and one did not. Unfortunately for the lobotomized monkey, it died before the exhibit opened -- but not before Freeman had previewed the monkeys for the press. The neurologist also received a bronze medal for his exhibit from the AMA.

- One can speculate on whether it might have been a gold medal had both monkeys survived. Reading about the monkey exhibit made me stop and think: what on earth was Freeman doing showing monkeys at a medical convention? How did he end up with a medal for it? Did no one think that was weird? I resolved to figure out what was going on.

- As I looked more closely at the culture of medical conventions like the AMA, I realized that exhibits like the one Freeman mounted were not anomalies but important features of professional medicine throughout most of the twentieth century. Almost every major state and national medical meeting included a scientific exhibit, in which physicians demonstrated discoveries for each other. It’s only been in the last thirty years that the tradition has faded into obscurity. And, in fact, it still lives on: in certain specialties, where exhibiting is still the norm, and in odd holdovers like the poster session, which, I’ll argue comes right out of the exhibiting tradition that Freeman so proudly participated in. My presentation today will give a history of exhibiting practices in professional medicine, starting at the beginning of the twentieth century and continuing to the early 1980s. I’ve chosen to focus on the American Medical Association conventions because they were, for so long, the largest American meetings and the site of such enthusiastic exhibiting. But the AMA was not alone in holding a scientific exhibit. Take a look at the program for almost any state or national medical convention in the middle of the twentieth century and you’ll see an exhibit component. The second part of my presentation gives my reading of what this all means. Why does it matter that physicians exhibited their discoveries? How should it change our understanding of how medicine is communicated and practiced? And why has the exhibit hall faded out of fashion?

- The second part of my presentation gives my reading of what this all means. Why does it matter that physicians exhibited their discoveries? How should it change our understanding of how medicine is communicated and practiced? And why has the exhibit hall faded out of fashion?

- The Scientific Exhibit began at the AMA in 1899, when an Indiana pathologist brought a collection of pathological specimens to the annual convention in Atlantic City. The pathology exhibit was a big hit -- so much so, in fact, that the exhibit hall had to be purged of curious mothers pushing baby carriages. The pathology exhibit took hold, and a few years later, in 1902, the scientific exhibit became an official feature of AMA annual conventions. Writing that same year, Frank Wynn, the Indiana pathologist who launched the trend, cited “the need for practical features which will entertain, instruct, and make plain the latest advances in medical science.” “Papers and reports are valuable in their way,” Wynn continued, “but seeing is believing. ... The Scientific Exhibit is in harmony with the spirit of the age which demands brevity; calls for facts rather than theories and deeds rather than words”

- Over the next few decades, the procedures for exhibiting became standardized, and in 1908 the AMA began awarding medals for the best exhibits. A physician or medical organization applied for booth space. If his or her application was successful, he or she received an allotment of space, which the physician was expected to fill with an entertaining and informative display.

- If the application was successful, the physician or organization received an allotment of booth space, which they were expected to fill with an entertaining and informative display.

- The AMA was especially adamant that a physician or other representative should be present at the booth to answer questions and offer demonstrations.

- By 1918, exhibiting was so popular that the AMA turned down half of its applications. The exhibit hall at annual conventions held as many as 250 different booths.

- Many of these exhibits contained an audiovisual component, and film became a source of controversy within the AMA exhibit hall. Convention organizers added motion-picture theaters to the exhibit hall in 1915, and the films, which were often surgical demonstrations, became a popular feature of the convention. Organizers, however, feared that the films were too popular, and in 1927 the exhibit committee voted to close the motion-picture theaters. Enterprising physician-filmmakers, however, could not be suppressed, and the films began to appear within the exhibit booths themselves. This was itself a problem, since spectators jammed the aisles. By 1941, the AMA had given up on banning film, and it re-opened the medical film theaters that year.

- Attendance at medical conventions dropped off during World War II, but by the end of the war physicians were returning to the AMA, and exhibiting with even greater enthusiasm. The 1957 convention, for example, featured 400 special exhibits.

- And as the exhibits increased in number, they also increased in the elaborateness of their presentation. At the 1947 exhibit, for example, an interested physician could visit the Special Exhibit on Cardiovascular Diseases, where he would see charts, drawings, diagrams, color slides, photographs, X-rays, live patients who would submit to examination, and demonstrators who could answer questions. If the physician felt inspire to learn more, he could attend a screening of a film on cardiovascular surgery in one of the convention’s three motion-picture theaters.

- As in previous years, physicians were encouraged to make their displays interactive and engaging, by providing audiovisual components

- and by engaging live subjects to undergo examination and demonstration.

- In 1948, a new medium joined film and exhibits in the convention hall: live, closed-circuit television. The broadcasts, which showed surgical demonstrations were seen as a substitute for the surgical ampitheater. Television became a fixture at medical meetings, as physicians lined up before a phalanx of individual sets, as they did here, or in front of one big screen.

- Around 1965, exhibiting began to decline in popularity. There are a few reasons for this, I think. First, as the ‘60s and ‘70s progressed, the AMA was no longer the major force it had been in the medical profession. The field began to divide into multiple specialties, and as doctors migrated to smaller, more specialized societies, there wasn’t the audience or the participation for a big exhibit hall. Second, the function of the AMA convention itself changed. Convention organizers began to bill AMA meetings as a place for physicians to garner continuing education credits, not as a place to show off new discoveries. In 1980, the AMA voted to discontinue the scientific exhibit altogether.

- But it wasn’t really the end of the exhibiting tradition. The 1980 resolution that put an end to the exhibit hall explicitly named the poster session as a substitute -- a tradition that continues in any number of medical societies.

- More than that, exhibiting still takes place in its older form within a number of societies and subfields. It’s still commonplace within radiology, for example, as well as orthopedic surgery and anesthesiology.

- And, although I can’t prove a connection, I think there’s more than a little bit of the exhibiting spirit in the ubiquity of PowerPoint presentations in professional medical culture today.

- So: who cares? What inferences can we draw from the popularity of medical exhibition during the twentieth century? Well, I have a few ideas about that. First, I think it should make us reexamine our ideas about how medical ideas are formed and communicated. When we think of how new medical techniques and theories are broadcast, we tend to think of journal articles, and sometimes lectures. But delving into the professional culture of the twentieth century suggests that we should also look to the engaged, interactive, multimedia environment of the exhibit hall.

- A second, related point comes from the fairground atmosphere of the medical exhibit hall: demonstrations, lights, sound, models. Physicians were instructed to scrub their exhibits of anything that might hint of advertising. And yet the scientific exhibit dwelled in close proximity to a second kind of exhibit: the technical exhibit, at which advertisers hawked their wares. Indeed, these technical exhibits persist at most major medical conventions today.

- Despite efforts of the physicians who scrubbed their booths of any advertising, I think the similarity of the scientific exhibit to the technical exhibit suggests that the professional culture of medicine has as much to do with the marketplace and the exhibit hall.

- In fact, I suspect that one reason that exhibitors were so conscientious about scrubbing any trace of showmanship from their exhibits was that they recognized these similarities to the marketplace and were made uncomfortable by them.

- Third, the general line on medicine and images is that medicine increasingly oriented itself toward the virtual, rather than the tangible, as the twentieth century progressed: witness CAT scans, X-rays, and virtual dissections. And yet, what should we make of the fact that the pathology exhibit, which arrayed organs for doctors to touch and feel, made its entrance into the medical profession during the same year as the X-ray? Does the exhibit hall, a forum where doctors could see and feel evidence with their own eyes and hands, suggest some points of tension in this neat trajectory? I was reminded of this seeming contradiction when I read this passage from Loraine Daston and Peter Galison, where the authors describe the transitions between modes of objectivity: “This is not some neat Hegelian arithmetic of thesis plus antithesis equals synthesis, but a far messier situation in which all the elements continue in play and interaction with each other.” Perhaps physicians conceded the dominance of virtual ways of seeing even as they used their own eyes and bodies to calibrate the new regime.

- Finally, it seems to me that this exhibiting tradition can help us to sense a current that runs throughout the epistemology of twentieth century medicine, and this has to do with what it means to display. To display something is to open it up, to make it visible for examination. The OED uses the provocative word “unfolding.” It seems to me that the exhibiting tradition hints at a medical imperative to unearth and array the contents of the body. Only by making data available to the eyes can a physician make the body knowable.

- Helen Miles Davis, the author of a 1955 instructional pamphlet on exhibiting, put it beautifully: “In science, you must know to show, and you must show to know.”