From Digital Images to Digital Research

- 1. From Digital Images to Digital Research Dr James Baker Curator, Digital Research @j_w_baker

- 2. www.bl.uk 2 Some adminĪŁ You are free to: ©C Copy, share, adapt, or re-mix ©C Photograph, film, or broadcast ©C Blog, live-blog, or post video of; this presentation provided that: ©C You attribute the work to its author and respect the rights and licences associated with its components ©C You distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one Text attribution Greg Wilson, Two Solitudes, SPLASH 2013 (29 October 2013) http://www.slideshare.net/gvwilson/splash-2013 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License unless stated otherwise.

- 3. www.bl.uk 3 More than resource discoveryĪŁ Ī░The emergence of the new digital humanities isnĪ»t an isolated academic phenomenon. The institutional and disciplinary changes are part of a larger cultural shift, inside and outside the academy, a rapid cycle of emergence and convergence in technology and cultureĪ▒ Steven E Jones, Emergence of the Digital Humanities (2014)

- 4. www.bl.uk 4

- 5. www.bl.uk 5

- 6. www.bl.uk 6 Ī░Literary scholars and historians have in the past been limited in their analyses of print culture by the constraints of physical archives and human capacity. A lone scholar cannot read, much less make sense of, millions of newspaper pages. With the aid of computational linguistics tools and digitized corpora, however, we are working toward a large-scale, systemic understanding of how texts were valued and transmitted during this periodĪ▒ David A. Smith, Ryan Cordell, and Elizabeth Maddock Dillon, Ī«Infectious Texts: Modeling Text Reuse in Nineteenth-Century NewspapersĪ» (2013) http://www.ccs.neu.edu/home/dasmith/infect-bighum-2013.pdf

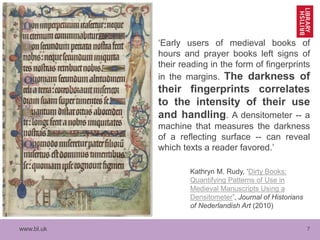

- 7. www.bl.uk 7 Ī«Early users of medieval books of hours and prayer books left signs of their reading in the form of fingerprints in the margins. The darkness of their fingerprints correlates to the intensity of their use and handling. A densitometer -- a machine that measures the darkness of a reflecting surface -- can reveal which texts a reader favored.Ī» Kathryn M. Rudy, Ī«Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a DensitometerĪ», Journal of Historians of Nederlandish Art (2010)

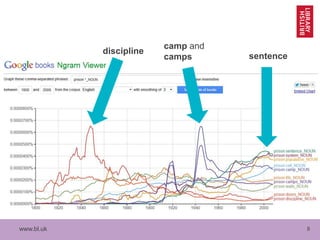

- 8. www.bl.uk 8 discipline camp and camps sentence

- 9. www.bl.uk 9 (c) Associated Newspapers Ltd. / Solo Syndication, British Cartoon Archive, University of Kent, Mac [Stan McMurtry], Daily Mail, 13 July 1973. Request Problem Processing Analysis Results

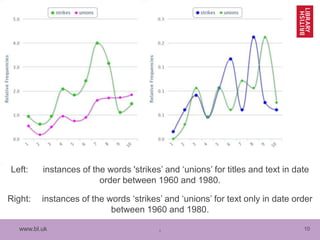

- 10. www.bl.uk 10 Left: instances of the words 'strikesĪ» and Ī«unionsĪ» for titles and any associated text in date order between 1960 and 1980. Right: instances of the words Ī«strikesĪ» and Ī«unionsĪ» for titles only in date order between 1960 and 1980. .

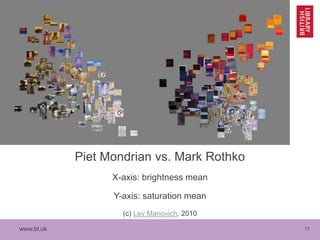

- 11. www.bl.uk 11 Piet Mondrian vs. Mark Rothko X-axis: brightness mean Y-axis: saturation mean (c) Lev Manovich, 2010

- 12. www.bl.uk 12

- 13. www.bl.uk 13

- 14. www.bl.uk 14

- 15. www.bl.uk 15

- 16. www.bl.uk 16 Ī«Overall, the identity of the data creator is less important than expected [...] Content found on online sites is tested against a set of finely- tuned ideas about the normal range of documents rather than the authority of the digitiserĪ» Mia Ridge, 'Early PhD findings: Exploring historians' resistance to crowdsourced resources' (19 March 2014)

- 17. www.bl.uk 17 Michael Hancher: blog, exercise

- 18. www.bl.uk 18 Ī«[T]he very phrase Ī«digital historyĪ» suggests separateness from, or the existence of, Ī«non-digitalĪ» historical practice. This seems highly problematic though. Both the idea that Ī«digital historyĪ» constitutes a specific sub-discipline, existing next to other historical sub-disciplines such as cultural, social, political or gender history, as well as the idea that it should essentially be seen as an auxiliary science of history, feed into the myth that historical practice in general can be uncoupled from technological, and thus methodological, developments and that going digital is a choice, which, I cannot emphasise strongly enough, it is not.Ī» Gerben Zaagsma, Ī«On Digital HistoryĪ», BMGN - Low Countries Historical Review 128:4 (2013)

- 19. www.bl.uk 19 Thank you! @j_w_baker james.baker@bl.uk http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/digital-scholarship/ ║▌║▌▀Żs: http://slidesha.re/1juAjUf Notes: http://bit.ly/1lDW3d9

![www.bl.uk 9

(c) Associated Newspapers Ltd. / Solo

Syndication, British Cartoon Archive,

University of Kent, Mac [Stan McMurtry],

Daily Mail, 13 July 1973.

Request

Problem

Processing

Analysis

Results](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2014-05-19outalkslides-140519042406-phpapp02/85/From-Digital-Images-to-Digital-Research-9-320.jpg)

![www.bl.uk 16

Ī«Overall, the identity of the

data creator is less

important than expected

[...] Content found on online sites

is tested against a set of finely-

tuned ideas about the normal

range of documents rather than

the authority of the digitiserĪ»

Mia Ridge, 'Early PhD findings:

Exploring historians' resistance

to crowdsourced resources' (19

March 2014)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2014-05-19outalkslides-140519042406-phpapp02/85/From-Digital-Images-to-Digital-Research-16-320.jpg)

![www.bl.uk 18

Ī«[T]he very phrase Ī«digital historyĪ»

suggests separateness from, or

the existence of, Ī«non-digitalĪ» historical

practice. This seems highly

problematic though. Both the idea

that Ī«digital historyĪ» constitutes a specific

sub-discipline, existing next to other

historical sub-disciplines such as

cultural, social, political or gender

history, as well as the idea that it should

essentially be seen as an auxiliary

science of history, feed into the myth

that historical practice in

general can be uncoupled from

technological, and thus

methodological, developments and that

going digital is a choice, which, I cannot

emphasise strongly enough, it is not.Ī»

Gerben Zaagsma, Ī«On Digital

HistoryĪ», BMGN - Low Countries

Historical Review 128:4 (2013)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2014-05-19outalkslides-140519042406-phpapp02/85/From-Digital-Images-to-Digital-Research-18-320.jpg)