Gme journal6

- 1. GME Journal ClubSukanya Sil, MDInternal Medicine PGY-1October 19, 2010

- 2. Annals of Internal Medicine3 Aug. 2010, Annals Vol. 153, p147-157Weight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years on a Low-Carbohydrate Versus Low-Fat Diet: A Randomized Trial3 Aug. 2010, Annals Vol. 153, p147-157.

- 3. OverviewWeight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years on a Low-Carbohydrate Versus Low-Fat Diet: A Randomized Trial OverviewBackgroundObjectiveDesignPatientsInterventionMeasurementsResultsLimitationsUSRDA ArticleOVERVIEWReferencesRecap

- 4. Weight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years on a Low-Carbohydrate Versus Low-Fat Diet: A Randomized Trial Data from several randomized trials over the past 6 years demonstrated that low-carbohydrate diets produced greater short-term (6 months) weight loss than low-fat, calorie-restricted diets. The longer-term (1 to 2 years) results are mixed.Some studies found greater weight loss with low-carbohydrate diets than with low-fat diets whereas others found no difference However, weight loss with either diet was usually minimal presumably because of the modest dose of behavioral treatment provided in these studies.BACKGROUND

- 5. Weight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years on a Low-Carbohydrate Versus Low-Fat Diet: A Randomized Trial The only 2-year randomized, controlled trial of a low-carbohydrate diet to date found greater 2-year weight loss with a low carbohydrate than a low-fat diet (6).The Israel-based study used visual prompts in a cafeteria setting to guide the selection of the main meal (lunch). Whether the results would be similar in different settings and cultures is unknown.Few previous studies have evaluated the effect of low-carbohydrate diets on symptoms or bone, and the assessments have been limited to 6 months (3, 4).BACKGROUND

- 6. ObjectiveData from several randomized trials over the past 6 years demonstrated that low-carbohydrate diets produced greater short-term (6 months) weight loss than low-fat, calorie-restricted diets. DesignDesign: randomized, 3-center parallel-group trial. (ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT00143936)Recruitment and data collection from three academic medical centers:OBJECTIVE&DESIGNUniversity of PennsylvaniaUniversity of Colorado, DenverWashingtonUniversity Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaDenver, ColoradoSt. Louis, Missouri

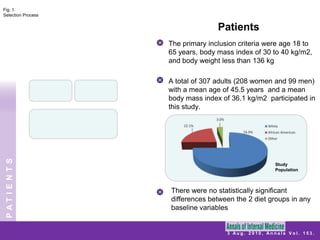

- 7. PatientsFig. 1. Selection ProcessThe primary inclusion criteria were age 18 to 65 years, body mass index of 30 to 40 kg/m2, and body weight less than 136 kgA total of 307 adults (208 women and 99 men) with a mean age of 45.5 years and a mean body mass index of 36.1 kg/m2 participated in this study.PATIENTSStudyPopulationThere were no statistically significant differences between the 2 diet groups in any baseline variables

- 8. PatientsAll participants completed a comprehensive medical examination and routine blood tests.PATIENTS* Tracked March 2003 to June 2007

- 9. InterventionA low-carbohydrate diet consisting of: limited carbohydrate intake (20 g/d for 3 months)

- 11. unrestricted consumption of fat and protein.After 3 months, participants in the low-carbohydrate diet group increased their carbohydrate intake (5 g/d per wk) until a stable and desired weight was achieved.A low-fat diet consisted of limited energy intake (1200 to 1800 kcal/d; 30% calories from fat).Both diets were combined with comprehensive behavioral treatmentINTERVENTION

- 12. InterventionAll participants received comprehensive, in-person group behavioral treatment: initially weekly for 20 weeks, every other week for 20 weeks.

- 14. each treatment session lasted 75 to 90 minutes. Topics included self-monitoring, stimulus control, and relapse management. All participants were prescribed the same level of physical activity (principally walking),beginning at week 4, with 4 sessions of 20 minutes each and progressing by week 19 to 4 sessions of 50 minutes each. Group sessions reviewed participants’ completion of their eating and activity records, as well as other skill buildersINTERVENTION

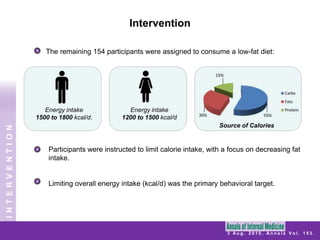

- 15. InterventionThe remaining 154 participants were assigned to consume a low-fat diet:Energy intake 1500 to 1800 kcal/d.Energy intake1200 to 1500 kcal/dSource of CaloriesParticipants were instructed to limit calorie intake, with a focus on decreasing fat intake. Limiting overall energy intake (kcal/d) was the primary behavioral target.INTERVENTION

- 16. MeasurementsWeight at 2 years was the primary outcome.Secondary measures included: weight at 3, 6, and 12 months

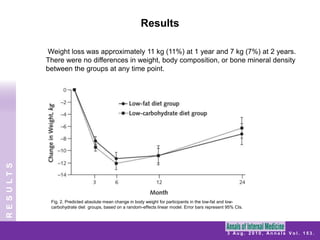

- 23. Results Weight loss was approximately 11 kg (11%) at 1 year and 7 kg (7%) at 2 years. There were no differences in weight, body composition, or bone mineral density between the groups at any time point.RESULTSFig. 2. Predicted absolute mean change in body weight for participants in the low-fat and low-carbohydrate diet groups, based on a random-effects linear model. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

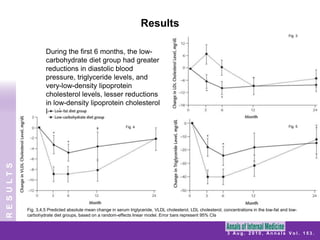

- 24. ResultsFig. 3During the first 6 months, the low-carbohydrate diet group had greater reductions in diastolic blood pressure, triglyceride levels, and very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, lesser reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels.Fig. 5Fig. 4RESULTSFig. 3,4,5Predicted absolute mean change in serum triglyceride, VLDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, concentrations in the low-fat and low-carbohydrate diet groups, based on a random-effects linear model. Error bars represent 95% CIs

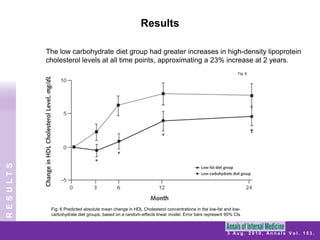

- 25. ResultsThe low carbohydrate diet group had greater increases in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels at all time points, approximating a 23% increase at 2 years.Fig. 6RESULTSFig. 6Predicted absolute mean change in HDL Cholesterol concentrations in the low-fat and low-carbohydrate diet groups, based on a random-effects linear model. Error bars represent 95% CIs

- 26. ResultsA significantly greater percentage of participants who consumed the low-carbohydrate than the low-fat diet experienced: bad breath

- 29. dry mouthExcept for constipation, all of these differences were limited to the first 6 months of treatment.No serious cardiovascular events (for example, stroke, myocardial infarction) were reportedRESULTS

- 30. LimitationsThe comprehensive behavioral therapy program used in this study makes it difficult to extrapolate results to general weight management. The clinically significant weight losses achieved at 24 months underscore the need for providing patients with long-term behavioral support, either by registered dietitians or other allied health professionals. The protocol was based on an Atkins version of a low-carbohydrate plan, which prescribes an increase in carbohydrate intake over time; thus, the effects of longer than 12 weeks of severe (20 g/d) carbohydrate restriction could not be assessed. Findings should not be generalized to obese persons who have obesity-related diseasesLIMITATIONS

- 31. ConclusionOverviewIn this randomized trial, participants took part in a comprehensive lifestyle modification program and were assigned to either a low-carbohydrate or low-fat diet. Previous trials comparing low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets have generally not included concurrent lifestyle modification. Weight loss in both groups was approximately 7 kg at 2 years, and weight, body composition, and bone mineral density did not differ between the groups at any time point. Low-carbohydrate diet group had greater increases in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels at all time points. Successful weight loss can be achieved with either a low-fat or low-carbohydrate diet when coupled with behavioral treatment.A low-carbohydrate diet is associated with favorable changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors at 2 years.CONCLUSION

- 32. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services U.S. Department of Agriculture

- 33. Dietary GuidelinesDietary Guidelines for Americans provides science-based advice to promote health and to reduce risk for major chronic diseases through diet and physical activity. Major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States are related to poor diet and a sedentary lifestyle. Some specific diseases linked to poor diet and physical inactivity include cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, and certain cancers.Dietary Guidelines summarize and synthesize knowledge regarding individual nutrients and food components into recommendations for a pattern of eating that can be adopted by the public. Key Recommendations are grouped under nine inter-related focus areas. The recommendations are based on the preponderance of scientific evidence for lowering risk of chronic disease and promoting health. USRDA ARTICLEDietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 Dept. of Health and Human Services, Dept. of Agriculture

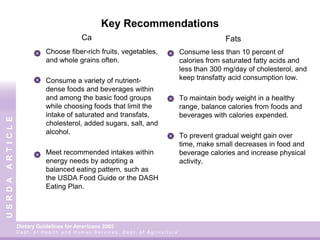

- 34. Key Recommendations CaFats Choose fiber-rich fruits, vegetables, and whole grains often. Consume a variety of nutrient-dense foods and beverages within and among the basic food groups while choosing foods that limit the intake of saturated and transfats, cholesterol, added sugars, salt, and alcohol. Meet recommended intakes within energy needs by adopting a balanced eating pattern, such as the USDA Food Guide or the DASH Eating Plan.Consume less than 10 percent of calories from saturated fatty acids and less than 300 mg/day of cholesterol, and keep transfatty acid consumption low.To maintain body weight in a healthy range, balance calories from foods and beverages with calories expended. To prevent gradual weight gain over time, make small decreases in food and beverage calories and increase physical activity.USRDA ARTICLEDietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 Dept. of Health and Human Services, Dept. of Agriculture

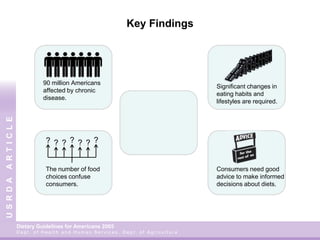

- 35. Key Recommendations The more we learn about nutrition the more we recognize their importance in everyday life. Americans of all ages may reduce their risk of chronic disease by adopting a nutritious diet.More than 90 million Americans are affected by chronic diseases and conditions that compromise their quality of life and well-being. Overweight and obesity, which are risk factors for diabetes and other chronic diseases, are more common than ever before. To correct this problem, many Americans must make significant changes in their eating habits and lifestyles. We live in a time of widespread availability of food options and choices. More so than ever, consumers need good advice to make informed decisions about their diets. USRDA ARTICLEDietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 Dept. of Health and Human Services, Dept. of Agriculture

- 36. Key Findings90 million Americansaffected by chronic disease.Significant changes in eating habits and lifestyles are required.???????USRDA ARTICLEThe number of food choices confuse consumers.Consumers need good advice to make informed decisions about diets. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 Dept. of Health and Human Services, Dept. of Agriculture

- 37. RecapWeight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years on a Low-Carbohydrate Versus Low-Fat Diet: A Randomized Trial OverviewBackgroundObjectiveDesignPatientsInterventionMeasurementsResultsLimitationsUSRDA ArticleRECAPReferencesRecap3 Aug. 2010, Annals Vol. 153.

- 38. References1. Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, McGuckin BG, Brill C, Mohammed BS, et al. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2082-90. [PMID: 12761365]2. Samaha FF, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, Chicano KL, Daily DA, McGrory J, et al. A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2074-81. [PMID: 12761364]3. Brehm BJ, Seeley RJ, Daniels SR, D’Alessio DA. A randomized trial comparing a very low carbohydrate diet and a calorie-restricted low fat diet on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women. J Clin Endocrinology Metab. 2003;88:1617-23. [PMID: 12679447]4. Yancy WS Jr, Olsen MK, Guyton JR, Bakst RP, Westman EC. A lowcarbohydrate,ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipid- Article Weight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years on a Low-Carbohydrate Versus Low-Fat Diet156 3 August 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 153 • Number 3 www.annals.org emia: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:769-77.[PMID: 15148063]5. Gardner CD, Kiazand A, Alhassan S, Kim S, Stafford RS, Balise RR, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: the A TO Z Weight Loss Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:969-77. [PMID:17341711]6. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I, et al; Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT) Group. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:229-41. [PMID: 18635428]REFERENCES