Indexing Photographs

- 1. Indexing of Special Formats and Genres: Photographs Kathy Lulofs and Bradley Shipps IST 638, March 2009

- 2. Photographs as Information Photographs are powerful tools for the transfer of information. In newspapers and magazines, on the Internet, and wherever they are found, photographs often convey information not found in the related text. Even in the absence of text, a photograph can speak volumes. The indexer faces the challenge of using words to provide access to the information contained in images .

- 3. Key Issues in Indexing Photos Lack of standard practices Indexing photo-specific facets Lack of inherent metadata No title or author indicated No accompanying text, little known about some images How much indexing is enough? Dealing with backlogs of unprocessed images Should photos be indexed at the group or item level? Challenges of subject analysis Topical, narrative, emotive Identifying levels of analysis Interpreting relationships between the elements in an image A multitude of perspectives User terms vs. controlled vocabulary Achieving consistency among indexers applying subject terms

- 4. Lack of Standard Practices There is no consensus among indexers about what attributes of a photograph should be indexed. Often indexers have tried to apply document-oriented indexing practices to photographs, with limited success. In a 2007 article, Beaudoin cites several obstacles to providing access to visual resources. Lack of agreement on types of information needed Lack of universally applied schema Lack of use of standard vocabularies and schema Lack of subject indexing Lack of user studies In addition to traditional subject analysis that is commonly used to index texts, the indexer of photographs might consider facets such as type of camera, developing process, camera angle, time of day, and location. Information about provenance might provide important historical context, and therefore should be indexed as well. These choices should be made with the intended audience of the photographs and index in mind.

- 5. Lack of Inherent Metadata Further research in the collection as a whole indicates that this photo was taken by Arvin Almquist, superintendent of Green Lakes State Park. It was probably taken in 1933 and the people in the photo are members of the Civilian Conservation Corps who are clearing a new road to the camp. That is interesting! But it took some work to gather the information that will inform our indexing. Jacobs (1999) aptly states, âthe media themselves do not allow for easy incorporation of access points, as in back-of-the-book indexes.â When photographs do not have accompanying textual descriptions, indexing requires preliminary research and fact-checking. But how would we index this photo if we did not find answers to our questions? Would it even be worth doing? Who took this photo? When and where was it taken? Who are these people and what are they doing? Is it significant? To whom?

- 6. How much indexing is enough? Several articles we found on the subject of indexing photographs mention a vast backlog of unprocessed photographs found in archives of all kinds. Processing photographs requires significant labor and time. Historically, visual materials were given lower priority than text documents in libraries and archives. Item-level description was the stated ideal, but also considered impractical, and rarely achieved. If photographs were processed at all, indexing was often performed at the collection level with the assumption that serious researchers would examine an entire collection to find what they needed. However, with the advent of digitization, there is a new urgency around making photographic collections available quickly and efficiently. While digital collections largely circumvent the problems of arrangement of photo archives, they require more robust indexing--item-level image description--to facilitate discovery and retrieval. Indexers of photos must strike a balance between exhaustivity and productivity. â It seems likely thatâĶ researchers would prefer to have more images available to them, despite a reduction in metadata quality, than to have a few perfectly cataloged images and a large backlogâ (Foster 2006, 116).

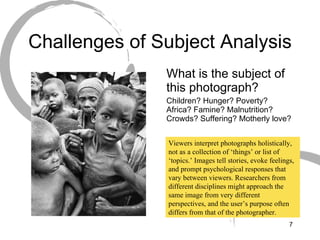

- 7. Challenges of Subject Analysis What is the subject of this photograph? Children? Hunger? Poverty? Africa? Famine? Malnutrition? Crowds? Suffering? Motherly love? Viewers interpret photographs holistically, not as a collection of âthingsâ or list of âtopics.â Images tell stories, evoke feelings, and prompt psychological responses that vary between viewers. Researchers from different disciplines might approach the same image from very different perspectives, and the userâs purpose often differs from that of the photographer.

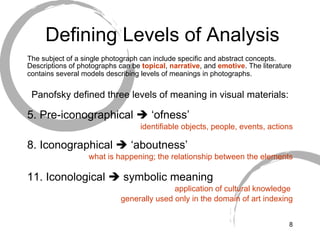

- 8. Defining Levels of Analysis The subject of a single photograph can include specific and abstract concepts. Descriptions of photographs can be topical , narrative , and emotive . The literature contains several models describing levels of meanings in photographs. Panofsky defined three levels of meaning in visual materials: Pre-iconographical ïĻ âofnessâ identifiable objects, people, events, actions Iconographical ïĻ âaboutnessâ what is happening; the relationship between the elements Iconological ïĻ symbolic meaning application of cultural knowledge generally used only in the domain of art indexing

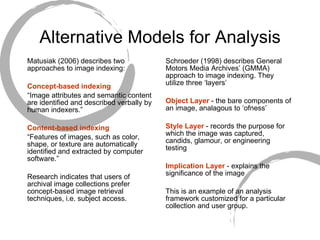

- 9. Alternative Models for Analysis Matusiak (2006) describes two approaches to image indexing: Concept-based indexing â Image attributes and semantic content are identified and described verbally by human indexers.â Content-based indexing â Features of images, such as color, shape, or texture are automatically identified and extracted by computer software.â Research indicates that users of archival image collections prefer concept-based image retrieval techniques, i.e. subject access. Schroeder (1998) describes General Motors Media Archivesâ (GMMA) approach to image indexing. They utilize three âlayersâ Object Layer - the bare components of an image, analagous to âofnessâ Style Layer - records the purpose for which the image was captured, candids, glamour, or engineering testing Implication Layer - explains the significance of the image This is an example of an analysis framework customized for a particular collection and user group.

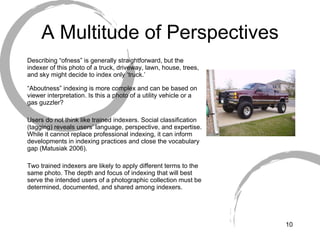

- 10. A Multitude of Perspectives Describing âofnessâ is generally straightforward, but the indexer of this photo of a truck, driveway, lawn, house, trees, and sky might decide to index only âtruck.â â Aboutnessâ indexing is more complex and can be based on viewer interpretation. Is this a photo of a utility vehicle or a gas guzzler? Users do not think like trained indexers. Social classification (tagging) reveals usersâ language, perspective, and expertise. While it cannot replace professional indexing, it can inform developments in indexing practices and close the vocabulary gap (Matusiak 2006). Two trained indexers are likely to apply different terms to the same photo. The depth and focus of indexing that will best serve the intended users of a photographic collection must be determined, documented, and shared among indexers.

- 11. Best Practices Focus on use Know your intended users and their needs Use controlled vocabulary Be responsive to user vocabulary Determine the levels of meaning to be indexed and create guidelines to ensure consistent indexing

- 12. Annotated Bibliography Beaudoin, J. E. (2007). Visual materials and online access: issues concerning content representation. Art Documentation , 26 (2), 24-8. Retrieved March 13, 2009, from Library Lit & Inf Full Text database. Beaudoin provides a holistic overview of the current research and problems related to intellectual access to visual materials. Access to images has traditionally been given short shrift in libraries and archives, but a recent push to âmake it all availableâ online has exposed five aspects of indexing images that are in need of further development. These include types of information, schemas, standardized vocabularies and classification systems, subject indexing, and user studies. Beaudoin addresses each aspect in turn, presenting a challenge to the indexing community to research and overcome these obstacles to image access. Burke, M.A. (1999). Organization of Multimedia Resources: Principles and Practice of Information Retrieval . Brookfield, VT: Gower Publishing Limited. Burke wrote a fantastic book about the different rules and classification that goes into indexing collections that are out of the ânorm.â Not only does she provide excellent screen shots of how to index better on the computer, and give examples that are great for extra reading but she also points users to very in-depth sites to help a newbie able to index special collections. Foster, A. L. (2006). Minimum standards processing and photograph collections. Archival Issues , 30 (2), 107-18. Retrieved March 13, 2009, from Library Lit & Inf Full Text database. Foster describes her efforts to extend the âMore Product, Less Processâ (MPLP) archive management strategy proposed by Greene and Meissner in a 2005 article of the same name, to the photographic collections at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) Archive. Foster makes an excellent case for adopting minimum standards processing of photos, and provides a review of the archives photo processing practices at UAF from 1966 to the present.

- 13. Â Jacobs, C. (1999, April). If a picture is worth a thousand words, thenâĶ Indexer , 21 (3), 119-121. Retrieved March 13, 2009, from Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts database. Jacobs presents an overview of the social role of images and outlines the central problems in image indexing, focusing on subject access to photographs, films, and clip art. This article is a brief but helpful introduction to image indexing. Li, J., & Wang, J. Z. (2003). Automatic linguistic indexing of pictures by a statistical modeling approach. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 25 (9), 1075-1088. Retrieved March 13, 2009, from http: //ieeexplore . ieee .org/ielx5/34/27551/01227984. pdf ? arnumber=1227984 Li and Wang explain how a computer can be trained to automatically index and build search terms for each item that is going into their database. Not only is this a very important tool to use, it eliminates human error and the possibility of certain photographs being assigned the wrong terms. This is significantly helpful in the start up of a new photographic database. Library of Congress. (2004). Subject Indexing with TGM: A Case Study in Selecting Access Points for Photographs . Retrieved March 24, 2009, from Cataloging & Digitizing Toolbox: http://www.loc. gov/rr/print/tp/SubjectAccessHineCaseStudy . pdf Compiled by Karen Chittenden, this document contains guidelines and examples used to train interns and volunteers at the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division to select subject access terms from the Thesaurus of Graphic Materials (TGM) . Presents four categories of terms to simplify selection: People, Building or Environment, Activity, and Objects. I plan to share this document with the CLRC digitization committee to possibly incorporate into our metadata training for contributors to the CNY Heritage digital library. Â

- 14. Â Library of Congress. (2008). Cataloging & Digitizing Toolbox . Retrieved March 24, 2009, from Prints & Photographs Reading Room: http://www.loc. gov/rr/print/cataloging .html This site compiles cataloging tools, "How to" tip sheets, resource lists, articles and presentations related to cataloging prints and photographs. What is really nice about this site is not only the fact it is LOC, but it is also Indexed very well to show a person how to go to the specific region where the information is stored. The LOC calls this site their Cataloging and Digitizing Toolbox. Matusiak, K. K. (2006). Towards user-centered indexing in digital image collections. OCLC Systems & Services , 22 (4), 283-98. Retrieved March 13, 2009, from Library Lit & Inf Full Text database. Matusiak explores the efficacy of user tagging of digital image collections relative to professional indexing using standardized schema and controlled vocabularies. She concludes that professional indexing is more consistent than user-generated metadata, but that user tagging can bridge the gap between usersâ language and controlled vocabularies and inform improvements in image indexing. Her literature review on image indexing provides an excellent overview of challenges in the field, and she quotes Dr. Kwasnik on page 294. Millar, R. (1999). The little collection that could: building an online index to historical photos. Art Libraries Journal , 24 (3), 25-9. Retrieved March 13, 2009, from Library Lit & Inf Full Text database. Millar explains starting a collection from scratch which includes many different kinds of photographs. Not only were they able to explore new words in order to describe the different aspects of the photographs involved but they were able to make a system easily transferable to a computer based format.

- 15. Â O'Connor, B. C., & O'Connor, M. K. (1999). Categories, photographs & predicaments: exploratory research on representing pictures for access. Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science , 25 (6), 17-20. Accessed March 13, 2009, http://www. asis .org/Bulletin/Aug-99/o_connor.html Although generally focused more on types of queries and the effects of indexing on retrieval than direct problems of original indexing, this article provides several excellent examples of the various ways lay users describe images. Notably, in addition to topical labels, users apply narrative and emotive labels to images and often assign geographic labels even in the absence of any geographic indicators in the image. Parker, E. B. (1987). LC Thesaurus for Graphic Materials: Topical Terms for Subject Access. Washington, D.C.: Cataloging Distribution Service, Library of Congress. This thesaurus contains over 3,000 authorized and 2,500 entry terms. The purpose of the thesaurus is to enable all forms of graphic materials to be properly indexed. Not only is the thesaurus of use to catalogers but also to researchers. With this tool one can easily and accurately index any form of graphic representation one might have. Schroeder, K. A. (1998). Layered indexing of images. The Indexer , 21 (1), 11-14. Retrieved March 13, 2009, from Library Lit & Inf Full Text database. Schroeder describes the indexing strategy developed for a large digitization project at the General Motors Media Archives (GMMA), which houses more than 3,000,000 photographs. GMMA employs a three-layered indexing system that accounts for objects, style, and implication for each photo. The indexing guidelines and examples are specific to GMâs information needs, but the article is useful as an example of indexing images according to the needs of a specific user group and an illustration of the many levels of meaning that can be derived from or attached to an image.

- 16. Â Vermillion, J. (2007). Indexing images. Key Words , 15 (1), 12-14. Retrieved March 13, 2009, from Library Lit & Inf Full Text database. This very brief article relates Vermillionâs first foray into indexing photographs for a new ContentDM digital library at Eastern Washington University. The author found that her skills as a freelance back-of-book indexer were applicable to this new medium, but noted some quirks of indexing photos. Research was required to build adequate descriptions and the user need, or âscope of interest,â had to be determined in order to limit the number of index terms. This article might help the novice photo indexer find the courage to begin, but offers little in the way of detailed guidance or description of challenges.