Lecture Notes for Device management in Operating Systems

- 2. So farŌĆ” ’ü¼We have covered CPU and memory management ’ü¼Computing is not interesting without I/Os ’ü¼Device management: the OS component that manages hardware devices ’éĪProvides a uniform interface to access devices with different physical characteristics ’éĪOptimize the performance of individual devices

- 3. I/O hardware ’ü¼ I/O device hardware ’éĪ Many varieties ’ü¼ Device controller ’ü¼Conversion a block of bytes and I/O operations ’ü¼Performs error correction if necessary ’ü¼Expose hardware registers to control the device ’ü¼Typically have four registers: ŌĆó Data-in register to be read to get input ŌĆó Data-out register to be written to send output ŌĆó Status register (allows the status of the device to be checked) ŌĆó Control register (controls the command the device performs)

- 4. Device Addressing ’ü¼ How the CPU addresses the device registers? ’ü¼ Two approaches ’éĪDedicated range of device addresses in the physical memory ’ü¼Requires special hardware instructions associated with individual devices ’éĪMemory-mapped I/O: makes no distinction between device addresses and memory addresses ’ü¼Devices can be accessed the same way as normal memory, with the same set of hardware instructions

- 5. Device Addressing Illustrated Primary memory Device 1 Device 2 Memory addresses Memory-mapped I/Os Primary memory Device addresses Separate device addresses

- 6. Ways to Access a Device ’ü¼How to input and output data to and from an I/O device? ’ü¼Polling: a CPU repeatedly checks the status of a device for exchanging data + Simple - Busy-waiting

- 7. Ways to Access a Device ’ü¼Interrupt-driven I/Os: A device controller notifies the corresponding device driver when the device is available + More efficient use of CPU cycles - Data copying and movements - Slow for character devices (i.e., one interrupt per keyboard input)

- 8. Ways to Access a Device ’ü¼Direct memory access (DMA): uses an additional controller to perform data movements + CPU is not involved in copying data - I/O device is much more complicated (need to have the ability to access memory). - A process cannot access in-transit data

- 9. Ways to Access a Device ’ü¼Double buffering: uses two buffers. While one is being used, the other is being filled. ’éĪAnalogy: pipelining ’éĪExtensively used for graphics and animation ’ü¼So a viewer does not see the line-by-line scanning

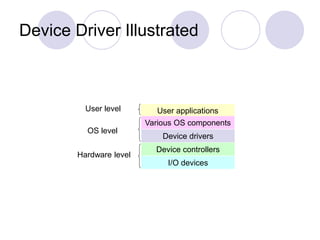

- 10. Device Driver ’ü¼An OS component that is responsible for hiding the complexity of an I/O device ’ü¼So that the OS can access various devices in a uniform manner

- 11. Types of IO devices ’ü¼ Two categories ’éĪ A block device stores information in fixed-size blocks, each one with its own address ’ü¼ e.g., disks ’éĪ A character device delivers or accepts a stream of characters, and individual characters are not addressable ’ü¼ e.g., keyboards, printers, network cards ’ü¼ Device driver provides interface for these two types of devices ’éĪ Other OS components see block devices and character devices, but not the details of the devices. ’éĪ How to effectively utilize the device is the responsibility of the device driver

- 12. Device Driver Illustrated User applications Various OS components Device drivers Device controllers I/O devices User level OS level Hardware level

- 13. Disk as An Example Device ’ü¼30-year-old storage technology ’ü¼Incredibly complicated ’ü¼A modern drive ’éĪ250,000 lines of micro code

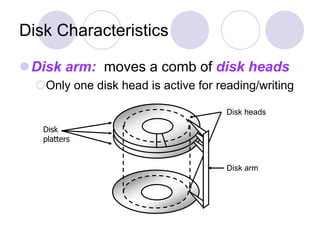

- 14. Disk Characteristics ’ü¼Disk platters: coated with magnetic materials for recording Disk platters

- 15. Disk Characteristics ’ü¼Disk arm: moves a comb of disk heads ’éĪOnly one disk head is active for reading/writing Disk platters Disk arm Disk heads

- 16. Hard Disk TriviaŌĆ” ’ü¼Aerodynamically designed to fly ’éĪAs close to the surface as possible ’éĪNo room for air molecules ’ü¼Therefore, hard drives are filled with special inert gas ’ü¼If head touches the surface ’éĪHead crash ’éĪScrapes off magnetic information

- 17. Disk Characteristics ’ü¼Each disk platter is divided into concentric tracks Disk platters Disk arm Disk heads Track

- 18. Disk Characteristics ’ü¼A track is further divided into sectors. A sector is the smallest unit of disk storage Disk platters Disk arm Disk heads Track Sector

- 19. Disk Characteristics ’ü¼A cylinder consists of all tracks with a given disk arm position Disk platters Disk arm Disk heads Track Sector Cylinder

- 20. Disk Characteristics ’ü¼Cylinders are further divided into zones Disk platters Disk arm Disk heads Track Sector Cylinder Zones

- 21. Disk Characteristics ’ü¼Zone-bit recording: zones near the edge of a disk store more information (higher bandwidth) Disk platters Disk arm Disk heads Track Sector Cylinder Zones

- 22. More About Hard Drives Than You Ever Want to Know ’ü¼ Track skew: starting position of each track is slightly skewed ’éĪMinimize rotational delay when sequentially transferring bytes across tracks ’ü¼ Thermo-calibrations: periodically performed to account for changes of disk radius due to temperature changes ’ü¼ Typically 100 to 1,000 bits are inserted between sectors to account for minor inaccuracies

- 23. Disk Access Time ’ü¼Seek time: the time to position disk heads (~8 msec on average) ’ü¼Rotational latency: the time to rotate the target sector to underneath the head ’éĪAssume 7,200 rotations per minute (RPM) ’éĪ7,200 / 60 = 120 rotations per second ’éĪ1/120 = ~8 msec per rotation ’éĪAverage rotational delay is ~4 msec

- 24. Disk Access Time ’ü¼Transfer time: the time to transfer bytes ’éĪAssumptions: ’ü¼58 Mbytes/sec ’ü¼4-Kbyte disk blocks ’éĪTime to transfer a block takes 0.07 msec ’ü¼Disk access time ’éĪSeek time + rotational delay + transfer time

- 25. Disk Performance Metrics ’ü¼Latency ’éĪSeek time + rotational delay ’ü¼Bandwidth ’éĪBytes transferred / disk access time

- 26. Examples of Disk Access Times ’ü¼If disk blocks are randomly accessed ’éĪAverage disk access time = ~12 msec ’éĪAssume 4-Kbyte blocks ’éĪ4 Kbyte / 12 msec = ~340 Kbyte/sec ’ü¼If disk blocks of the same cylinder are randomly accessed without disk seeks ’éĪAverage disk access time = ~4 msec ’éĪ4 Kbyte / 4 msec = ~ 1 Mbyte/sec

- 27. Examples of Disk Access Times ’ü¼If disk blocks are accessed sequentially ’éĪWithout seeks and rotational delays ’éĪBandwidth: 58 Mbytes/sec ’ü¼Key to good disk performance ’éĪMinimize seek time and rotational latency

- 28. Disk Tradeoffs ’ü¼Larger sector size ’āĀ better bandwidth ’ü¼Wasteful if only 1 byte out of 1 Mbyte is needed Sector size Space utilization Transfer rate 1 byte 8 bits/1008 bits (0.8%) 80 bytes/sec (1 byte / 12 msec) 4 Kbytes 4096 bytes/4221 bytes (97%) 340 Kbytes/sec (4 Kbytes / 12 msec) 1 Mbyte (~100%) 58 Mbytes/sec (peak bandwidth)

- 29. Disk Controller ’ü¼Few popular standards ’éĪIDE (integrated device electronics) ’éĪATA (AT attachment interface) ’éĪSCSI (small computer systems interface) ’ü¼Differences ’éĪPerformance ’éĪParallelism

- 30. Disk Device Driver ’ü¼Major goal: reduce seek time for disk accesses ’éĪSchedule disk request to minimize disk arm movements

- 31. Disk Arm Scheduling Policies ’ü¼First come, first serve (FCFS): requests are served in the order of arrival + Fair among requesters - Poor for accesses to random disk blocks ’ü¼Shortest seek time first (SSTF): picks the request that is closest to the current disk arm position + Good at reducing seeks - May result in starvation

- 32. Disk Arm Scheduling Policies ’ü¼SCAN: takes the closest request in the direction of travel (an example of elevator algorithm) + no starvation - a new request can wait for almost two full scans of the disk

- 33. Disk Arm Scheduling Policies ’ü¼Circular SCAN (C-SCAN): disk arm always serves requests by scanning in one direction. ’éĪOnce the arm finishes scanning for one direction ’éĪReturns to the 0th track for the next round of scanning

- 34. First Come, First Serve ’ü¼Request queue: 3, 6, 1, 0, 7 ’ü¼Head start position: 2 ’ü¼Total seek distance: 1 + 3 + 5 + 1 + 7 = 17 Tracks 0 5 4 3 2 1 6 7 Time

- 35. Shortest Seek Distance First ’ü¼Request queue: 3, 6, 1, 0, 7 ’ü¼Head start position: 2 ’ü¼Total seek distance: 1 + 2 + 1 + 6 + 1 = 10 Tracks 0 5 4 3 2 1 6 7 Time

- 36. SCAN ’ü¼Request queue: 3, 6, 1, 0, 7 ’ü¼Head start position: 2 ’ü¼Total seek distance: 1 + 1 + 3 + 3 + 1 = 9 Time Tracks 0 5 4 3 2 1 6 7

- 37. C-SCAN ’ü¼Request queue: 3, 6, 1, 0, 7 ’ü¼Head start position: 2 ’ü¼Total seek distance: 1 + 3 + 1 + 7 + 1 = 13 Time Tracks 0 5 4 3 2 1 6 7

- 38. Look and C-Look ’ü¼Similar to SCAN and C-SCAN ’éĪ the arm goes only as far as the final request in each direction, then turns around ’ü¼ Look for a request before continuing to move in a given direction.