Lifting Cost Rig Count Oil1 (2) (4) (2)

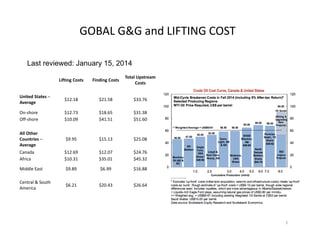

- 1. Lifting¬†Costs Finding¬†Costs Total¬†Upstream¬† Costs United¬†States¬†‚Äď Average $12.18 $21.58 $33.76 On‚Äźshore $12.73 $18.65 $31.38 Off‚Äźshore $10.09 $41.51 $51.60 All¬†Other¬† Countries¬†‚Äď Average $9.95 $15.13 $25.08 Canada $12.69 $12.07 $24.76 Africa $10.31 $35.01 $45.32 Middle¬†East $9.89 $6.99 $16.88 Central¬†&¬†South¬† America $6.21 $20.43 $26.64 GOBAL¬†G&G¬†and¬†LIFTING¬†COST Last reviewed: January 15, 2014 1

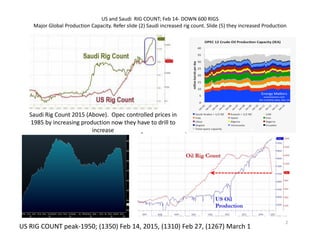

- 2. US¬†and¬†Saudi¬†¬†RIG¬†COUNT;¬†Feb¬†14‚Äź DOWN¬†600¬†RIGS Major¬†Global¬†Production¬†Capacity.¬†Refer¬†slide¬†(2)¬†Saudi¬†increased¬†rig¬†count.¬†ļ›ļ›Ŗ£¬†(5)¬†they¬†increased¬†Production¬† Saudi¬†Rig¬†Count¬†2015¬†(Above).¬†¬†Opec controlled¬†prices in¬† 1985¬†by¬†increasing¬†production¬†now¬†they¬†have¬†to¬†drill¬†to¬† increase US¬†RIG¬†COUNT¬†peak‚Äź1950;¬†(1350)¬†Feb¬†14,¬†2015,¬†(1310)¬†Feb¬†27,¬†(1267)¬†March¬†1 2

- 6. 6

- 7. 7

- 8. Costs A¬†major¬†factor¬†influencing¬†the¬†cost¬†of¬†extraction¬†is¬†the¬†lifecycle¬†of¬†each¬†type¬†of¬†oil¬†source.¬†Saudi¬†wells¬†last¬†longer.¬†There is more¬†oil¬†to¬†pump¬†within¬†each¬†cavity¬†and¬†so¬†the¬†cost¬†of¬†setting¬†up¬†that¬† well¬†can¬†be¬†written¬†off¬†over¬†a¬†longer¬†period¬†than¬†the¬†cost¬†of¬†setting¬†up¬†a¬†fracking¬†and¬†horizontal¬†drilling¬†operation.¬†A¬†long‚Äźterm¬†producer¬†can¬†also¬†write¬†off¬†the¬†cost¬†of¬†distribution¬†methods¬† over¬†a¬†longer¬†period.¬†So¬†if¬†a¬†new¬†well¬†can¬†be¬†built¬†alongside¬†existing¬†roads¬†and¬†pipelines,¬†that¬†method¬†will¬†end¬†up¬†cheaper¬†in¬†the¬†long¬†run¬†than¬†fracking¬†in¬†remote¬†and¬†previously¬†unexplored¬† areas¬†where¬†a¬†new¬†pipeline¬†or¬†railroad¬†infrastructure¬†adds¬†to¬†setup¬†costs.¬† Staff¬†costs¬†are¬†higher¬†with¬†fracking¬†methods¬†because¬†each¬†drilling¬†site¬†is¬†distant¬†from¬†earlier¬†sites.¬†Any¬†oil¬†extractor¬†has¬†to¬†spend¬†time¬†and¬†money¬†locating¬†staff¬†for¬†each¬†project.¬†Those¬† employees¬†then¬†need¬†to¬†be¬†transported¬†and¬†housed.¬†If¬†a¬†well¬†lasts¬†for¬†decades,¬†the¬†same¬†accommodation¬†can¬†be¬†used¬†for¬†staff¬†over a¬†longer¬†period¬†than¬†the¬†short‚Äźterm¬†nature¬†of¬†each¬†fracking¬† location.¬†The¬†peripatetic¬†nature¬†of¬†fracking¬†also¬†means¬†that¬†staff¬†will¬†be¬†less¬†likely¬†to¬†settle¬†in¬†one¬†place¬†with¬†their¬†families¬†and¬†therefore¬†demand¬†higher¬†wages¬†to¬†compensate¬†for¬†the¬† loneliness¬†of¬†working¬†away¬†from¬†home¬†in¬†freezing¬†‚Äź40F¬†North¬†Dakota¬†winters.¬† Capacity Fracking¬†is¬†more¬†expensive¬†than¬†extracting¬†oil¬†by¬†conventional¬†methods.¬†Thus,¬†conventional¬†producers¬†can¬†afford¬†to¬†keep¬†extracting¬†and¬†selling¬†their¬†oil¬†at¬†lower¬†crude¬†index¬†prices¬†than¬† frackers.¬†So¬†why¬†bother¬†investing¬†in¬†hydraulic¬†fracturing¬†and¬†horizontal¬†drilling?¬†A¬†high¬†oil¬†price¬†offers¬†an¬†incentive¬†to¬†endeavor.¬†American¬†oil¬†exploration¬†and¬†extraction¬†companies¬†would¬† much¬†rather¬†work¬†in¬†their¬†own¬†country,¬†and¬†in¬†their¬†own¬†language,¬†than¬†have¬†to¬†travel¬†to¬†unstable¬†places¬†and¬†risk¬†hostile¬†cultures¬†in¬†order¬†to¬†make¬†a¬†living.¬†Thus,¬†US¬†oil¬†companies¬†expanded¬† production¬†in¬†their¬†own¬†county once¬†prices¬†reached¬†a¬†certain¬†level¬†where¬†unconventional¬†methods¬†became¬†economically¬†viable.¬†Financiers¬†and¬†investors¬†had¬†little¬†risk¬†of¬†losing¬†their¬† investment.¬†The¬†OPEC¬†countries consistently¬†trimmed¬†their¬†output¬†to¬†match¬†world¬†demand,¬†so¬†projections¬†of¬†oil¬†prices¬†and¬†rates¬†of¬†return¬†created¬†a¬†one‚Äźway¬†bet.¬† American¬†oil¬†producers¬†could¬†just¬†keep¬†increasing¬†capacity¬†infinitely¬†(or¬†so¬†it¬†seemed),¬†because¬†someone¬†else¬†would¬†adjust¬†their output¬†to¬†make¬†room¬†in¬†the¬†market.¬†Prospects¬†looked¬†good¬†for¬† expansion¬†because¬†cutbacks¬†in¬†OPEC¬†production¬†meant¬†America¬†could¬†just¬†keep¬†taking¬†a¬†larger¬†and¬†larger¬†share¬†of¬†the¬†market.¬† Circumstances The¬†Saudis¬†and¬†their¬†cheap‚Äźoil¬†Persian¬†Gulf¬†neighbors¬†suddenly¬†had¬†enough¬†of¬†making¬†room¬†for¬†American¬†expansion.¬†They¬†knew¬†that¬†they¬†had¬†been¬†obliging¬†to¬†other¬†nations,¬†but¬†felt¬†that¬†they¬† had¬†not¬†been¬†treated¬†with¬†the¬†courtesies¬†that¬†they¬†deserved.¬†Saudi¬†Arabia¬†was¬†particularly¬†angry¬†that¬†America¬†and¬†its¬†Western allies¬†had¬†failed¬†to¬†topple¬†Bashar¬†al‚ÄźAssad¬†in¬†Syria and¬†they¬†were¬† furious¬†with¬†Russia¬†for¬†blocking¬†initial¬†attempts¬†to¬†oust¬†the¬†Syrian¬†president.¬†The¬†sudden¬†return¬†to¬†market¬†of¬†Algeria,¬†Libya and¬†Iraq¬†meant¬†that¬†OPEC¬†began¬†to¬†overproduce.¬†Under¬†normal¬† circumstances,¬†both¬†this¬†extra¬†production¬†and¬†added¬†capacity¬†from¬†fracking¬†would¬†have¬†prompted¬†the¬†Saudis¬†and¬†their¬†OPEC¬†allies¬†to¬†reduce¬†production¬†to¬†maintain¬†price¬†levels.¬†This¬†year,¬†the¬† Saudis¬†switched¬†tactics¬†and¬†decided¬†to¬†defend¬†their¬†market¬†share¬†no¬†matter¬†where¬†the¬†price¬†went.¬† Endgame A¬†falling¬†oil¬†price¬†punishes¬†Russia and¬†brings¬†economic¬†realities¬†to¬†calculations¬†over¬†whether¬†to¬†invest¬†in¬†further¬†oil¬†exploration.¬†Fortunately,¬†this¬†tactic¬†is¬†not¬†the¬†disaster¬†it¬†might¬†at¬†first¬†seem.¬† The¬†second¬†part¬†of¬†any¬†price¬†calculation¬†lies¬†with¬†demand¬†for¬†a¬†product.¬†At¬†the¬†same¬†time¬†that¬†oil¬†supply¬†surged,¬†demand¬†for¬†oil dropped.¬†China¬†maintained¬†the¬†illusion¬†of¬†growth¬†over¬†the¬†past¬† year¬†by¬†over‚Äźordering¬†raw¬†materials.¬†Now¬†¬†they¬†need¬†to¬†absorb¬†their¬†stocks,¬†which¬†takes¬†a¬†large¬†part¬†of¬†world¬†demand¬†for¬†oil¬†out¬†of¬†the¬†market.¬†Europe's¬†growth¬†is¬†stuttering,¬†removing¬†more¬† demand.¬†Economists¬†calculate¬†that¬†for¬†every¬†10%¬†drop¬†in¬†the¬†price¬†of¬†oil,¬†the¬†world's¬†GDP¬†will¬†grow¬†by¬†0.1%.¬†Evidently,¬†the¬†current¬†falls¬†in¬†oil¬†price¬†will¬†eventually¬†correct¬†the¬†lack¬†of¬†demand¬†in¬† the¬†market¬†and¬†supply¬†and¬†demand¬†will¬†return¬†to¬†equilibrium.¬† Pricing Faced¬†with¬†lack¬†of¬†demand¬†and¬†falling¬†prices,¬†any¬†business¬†has¬†three¬†options:¬†carry¬†on¬†regardless;¬†reduce,¬†or¬†suspend¬†production;¬†or¬†lower¬†costs.¬†Saudi¬†Arabia¬†chose¬†option¬†one.¬†This¬†strategy¬† relies¬†on¬†others¬†either¬†going¬†out¬†of¬†business,¬†or¬†suspending¬†operations¬†to¬†reduce¬†supply.¬†The¬†Arabian¬†producers¬†can¬†afford¬†to pick¬†that¬†option¬†because¬†they¬†have¬†the¬†lowest¬†production¬†costs¬† among¬†all¬†oil¬†producers.¬†According¬†to¬†Morgan¬†Stanley¬†Commodity¬†Research,¬†some¬†Middle‚ÄźEastern¬†onshore¬†production¬†can¬†break¬†even¬†at¬†$10¬†per¬†barrel.¬†Others¬†in¬†that¬†region¬†need¬†around¬†$37¬† per¬†barrel,¬†with¬†the¬†average¬†breakeven¬†point¬†for¬†onshore¬†wells¬†in¬†the¬†Gulf¬†states¬†at¬†around¬†$27¬†per¬†barrel.¬†US¬†shale¬†oil¬†doesn't start¬†to¬†pay¬†back¬†until¬†it¬†achieves¬†a¬†price¬†of¬†at¬†least¬†$50¬†per¬† barrel.¬†Current¬†production¬†costs¬†vary¬†between¬†that¬†breakeven¬†point¬†and¬†a¬†price¬†of¬†$80¬†per¬†barrel.¬† Long¬†Term¬†Effects The¬†depletion¬†rate¬†of¬†fracked¬†wells¬†is¬†high.¬†Bakken¬†production¬†for¬†any¬†given¬†fracked¬†well¬†declines¬†45¬†per¬†cent¬†per¬†year,¬†vs.¬†5¬†per¬†cent¬†per¬†year¬†for¬†conventional¬†wells. So after¬†one¬†year¬†the¬† same¬†well¬†produces¬†55%¬†of¬†its¬†initial¬†output,¬†after¬†two¬†years¬†that¬†reduces¬†to¬†30%,¬†and¬†only¬†17%¬†after¬†3¬†years.¬†Producers¬†need to keep¬†drilling¬†in¬†order¬†to¬†stay¬†in¬†production¬†with¬†a¬†steady¬†flow¬† of¬†oil.¬†This¬†series¬†of¬†wells¬†at¬†different¬†levels¬†of¬†depletion¬†in¬†production¬†by¬†the¬†same¬†company¬†is¬†termed¬†the¬†"drilling¬†treadmill."¬† Although¬†in¬†established¬†fracking¬†states,¬†such¬†as¬†Texas,¬†it¬†takes¬†only¬†seven¬†days¬†to¬†get¬†permits¬†to¬†start¬†extraction,¬†production¬†in¬†other¬†regions,¬†less¬†used¬†to¬†the¬†process¬†can¬†entail¬†months¬†of¬† delays¬†from¬†legislators¬†and¬†pressure¬†groups.¬†Environmental¬†restrictions¬†placed¬†on¬†potential¬†sites¬†can¬†pile¬†on¬†costs¬†and¬†make¬†the benefits¬†of¬†extending¬†the¬†method¬†into¬†new¬†locales¬†a¬†pricey¬† prospect.¬†Unfortunately¬†fracking¬†companies¬†have¬†already¬†exploited¬†the¬†easier,¬†larger¬†reserves.¬†Since¬†on¬†average¬†each¬†new¬†well has¬†a¬†fixed¬†start¬†up¬†cost¬†of¬†around¬†$9¬†million,¬†regardless¬†of¬†how¬† much¬†oil¬†it¬†will¬†produce,¬†further¬†expansion¬†of¬†shale¬†oil¬†production¬†will¬†only¬†break¬†even¬†north¬†of¬†the¬†current¬†$76‚Äź$77¬†level.¬† When¬†oil¬†sold¬†for¬†$100¬†per¬†barrel¬†producers¬†gained¬†a¬†margin¬†of¬†$23¬†per¬†barrel¬†after¬†a¬†cost¬†of¬†$77¬†per¬†barrel¬†for¬†drilling¬†the existing¬†wells¬†and¬†operating¬†them.¬†That¬†margin¬†provided¬†funding¬†for¬† the¬†"drilling¬†treadmill"¬†to¬†create¬†more¬†wells.¬†Therefore,¬†although¬†a¬†falling¬†price¬†may¬†not¬†cause¬†an¬†immediate¬†slow¬†down¬†in¬†production,¬†the¬†disincentive¬†of¬†lower¬†returns,¬†longer¬†delays¬†and¬† uncertain¬†rewards¬†could¬†discourage¬†future¬†development.¬†The¬†loss¬†of¬†a¬†profit¬†on¬†sales¬†means¬†fracking¬†companies¬†no¬†longer¬†have¬†money¬†to¬†keep¬†drilling¬†new¬†wells.¬†This¬†would¬†cause¬†a¬†reduction¬† in¬†America's¬†capacity¬†to¬†produce¬†oil¬†in¬†the¬†long¬†term.¬† 8