Postural Control from theory to practice.pptx

- 1. Postural control from theory to practice

- 2. HELLO! I am Heba el saeid PT. MSc. Neurological rehabilitation specialist at the Department of Neurology, Kasr al Ainy Medical School. Cofounder of Nervology educational platform 2

- 3. Postural Control Ō¢░ Postural control is the ability to maintain our body in space achieving both goals of stability and orientation. Ō¢░ Postural orientation is the ability to maintain an appropriate relationship between body segments, and between the body and the environment for a certain task. Ō¢░ Postural stability - also referred to as balance - is the ability to control the center of mass (COM) within the base of support (Bos). 3

- 4. 4

- 5. Three types of control Ō¢░ Steady-state balance is the ability to control our balance in fairly predictable and nonchanging conditions. Ō¢░ Reactive balance control is the ability to recover a stable position following an unexpected perturbation. Ō¢░ Proactive or anticipatory balance is the ability to activate muscles in the legs and trunk for balance control in advance of potentially destabilizing voluntary movements. 5

- 6. 6

- 7. Steady State Balance Ō¢░ Alignment of the body can minimize the effect of gravitational forces that tend to pull us off-center. Ō¢░ Postural tone to counteract the force of gravity the activity of the antigravity muscles increases during upright standing. Ō¢░ Movement strategies (Ankle, Hip) 7

- 8. Reactive Balance Control 1. Fixed support strategies: ankle and hip strategy. 2. Change in support strategies: the step strategy and the reach-to-grasp strategy. 8

- 10. Ankle strategy Ō¢░ Used most commonly in situations in which the perturbation to equilibrium is small and the support surface is firm. Ō¢░ Activation of the gastrocnemius produces a plantarflexion torque that slows and then reverses, the body's forward motion. 10

- 11. Hip strategy Ō¢░ This strategy controls motion by producing large and rapid motion at the hip joints, the hip strategy is used to restore equilibrium in response to larger, faster perturbations or when the support surface is smaller than the feet. 11

- 13. 13 Ō¢░ Step Strategy: A step strategy realigns the base of support under the falling center of mass by placing the feet in the direction of the perturbation Ō¢░ Grasp Strategy: relies on extending the BOS by using the arms to grasp an external object for stability.

- 14. 14 Ō¢░ Research has demonstrated that during recovery of stability, we continuously change and add multiple synergies, depending on the context of the task at hand. This suggests that when retraining balance, it will be important not to limit training to the activation of a single strategy (e.g., ankle vs. hip vs. step vs. reach) but to create conditions in which strategies are continuously modulated.

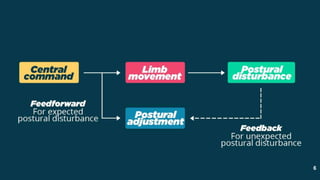

- 15. Anticipatory Balance Control 1. Fixed support strategies: ankle and hip strategy. 2. Change in support strategies: the step strategy and the reach-to-grasp strategy. 15

- 17. Goals Ō¢░ Modify (or prevent) impairments in body structure and function impacting postural control. Ō¢░ Improve the ability to meet the demands of balance (motor, sensory, and cognitive) during the performance of functional activities. Ō¢░ Improved participation which can be demonstrated by increased frequency of participation or increased independence and safety (reduced falls and near falls) when performing ADLs. 17

- 18. Treating Underlying Motor Impairments Ō¢░ Effect of strength training on balance: Among older adults, many studies have shown that resistance strength training is effective in increasing strength; however, while in some studies, this was associated with improved balance, in others, it was not. 18

- 19. Treating Underlying Motor Impairments Ō¢░ Functional Electrical Stimulation: FES to the lower extremity, particularly the ankle dorsiflexors, is used to improve performance in functional tasks such as standing and walking. But it was found that the position at which the stimulus is delivered matters. 19

- 20. Functional Balance Training: Improving Motor Strategies Training balance within the context of function includes: (1) Improving underlying movement strategies used for steady-state, reactive, and anticipatory balance control. (2) Adapting functional tasks to changing environmental conditions. 20

- 21. Steady-State Balance Control focuses on retraining orientation and alignment to help the patient develop an initial position that: (1) Is appropriate for the task. (2) Is efficient with respect to vertical alignment. (3) Maximizes stability, that is, places the vertical line of gravity well within the patient's stability limits. Many tasks use a symmetrical vertical position, but this may not be a realistic goal for all patients. 21

- 22. 22

- 23. Steady-State Balance Control HOW ABOUT ASSISTIVE DEVICES? 23

- 24. Retraining Reactive Balance Control Ō¢░ The goal when retraining reactive balance control is to help the patient develop coordinated multijoint movements, including both in-place and change-in-support strategiesŌĆ½ž▓ŌĆ¼ Ō¢░ Training involves exposing the patient to external perturbations that vary in direction, speed, and amplitude. Ō¢░ Small perturbations can facilitate the use of in-place strategies for balance control, while larger and faster perturbations encourage the use of a step or a reach. Ō¢░ Large perturbations in the standing position are combined with instructions to reach (or step) as quickly as possible. 24

- 25. Retraining Anticipatory Balance Control Ō¢░ Movement strategies to control the COM can also be practiced during voluntary sway in all directions. With practice, patients learn to control COM movements over increasingly larger areas while varying speed. Ō¢░ Patients who are very unsteady or extremely fearful of falling can practice movements while in the parallel bars or when standing close to a wall or in a corner with a chair or table in front of them. Ō¢░ When training anticipatory postural control, patients can be asked to carry out a variety of manipulation tasks, such as reaching, lifting, and throwing 25

- 26. Retraining Anticipatory Balance Control Ō¢░ The magnitude of anticipatory postural activity is directly related to the potential for instability inherent in a task. Potential instability relates to speed, effort, degree of external support, and task complexity. Ō¢░ Research provided evidence that anticipatory postural control training changes the timing at which lower limb muscles are activated before arm movements. 26

- 27. 27 THANKS!