Presentation Instrumentation and Quality Control.pptx

Download as PPTX, PDF0 likes11 views

Presentation Instrumentation and Quality Control

1 of 19

Download to read offline

Recommended

Assignment on errors

Assignment on errorsIndian Institute of Technology Delhi

╠²

This document discusses various types of errors that can occur when making measurements with instruments. It defines error as the difference between the expected and measured values. There are two main types of errors - static errors, which occur due to limitations in the instrument, and dynamic errors, which occur when the instrument cannot keep up with rapid changes. Static errors include gross errors from human mistakes, systematic errors due to instrument defects, and random errors from small unpredictable factors. The document provides examples of different sources of systematic errors like instrumentation errors, environmental influences, and observational errors. It also discusses methods for estimating random errors and other error types like limiting, parallax, and quantization errors.Quality assurance errors

Quality assurance errorsAliRaza1767

╠²

This document discusses types of errors that can occur in measurement. It describes absolute and relative errors, and how errors can be expressed. There are various sources of error, including the instrument, workpiece, person, and environment. Errors are classified as systematic/controllable or random. Systematic errors include calibration errors, environmental errors, stylus pressure errors, and avoidable errors. Random errors cause fluctuations that are positive or negative.Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptx

Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptxChinna Chadayan

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur in measurement. There are five main types of errors:

1) Gross errors are faults made by the person using the instrument, such as incorrect readings or recordings.

2) Systematic errors are due to problems with the instrument itself, environmental factors, or observational errors made by the observer.

3) Random errors remain after gross and systematic errors have been reduced and are due to unknown causes. Taking multiple readings and analyzing them statistically can help minimize random errors.

4) Absolute error is the difference between the expected and measured values.

5) Relative error expresses the error as a percentage of the real measurement.Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptx

Nursing Research Measurement errors.pptxChinna Chadayan

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur in measurement. There are five main types of errors:

1) Gross errors are faults made by the person using the instrument, such as incorrect readings or recordings.

2) Systematic errors are due to problems with the instrument itself, environmental factors, or observational errors made by the observer.

3) Random errors remain after gross and systematic errors have been reduced and are due to unknown causes. Taking multiple readings and analyzing them statistically can help minimize random errors.

4) Absolute error is the difference between the expected and measured values.

5) Relative error expresses the error as a percentage of the real measurement.Error in measurement

Error in measurementARKA JAIN University

╠²

Errors and uncertainties are inherent in the process of making any measurement and in the instrument with which the measurement are made. Errors in measurement

Errors in measurementPrabhaMaheswariM

╠²

Errors in measurement can be categorized as static, systematic, or random. Static errors represent the difference between the true and measured values. Systematic errors are due to issues with instruments, environments, or observations. Random errors occur due to sudden changes and can only be reduced by taking multiple readings. There are various types of systematic errors such as instrumental errors from shortcomings, misuse, or loading effects, and environmental errors from temperature, pressure, or other external conditions. Statistical analysis methods like finding the average, deviations, standard deviation, and variance can help determine the most probable value from a set of measurements.Errors and Error Measurements

Errors and Error MeasurementsMilind Pelagade

╠²

Thorough study of Experimental Errors occurred during experimentation using different experimental techniques.

A clear picture about techniques for error measurement is given in the presentation.Error analytical

Error analyticalLovnish Thakur

╠²

This document discusses experimental errors in scientific measurements. It defines experimental error as the difference between a measured value and the true value. Experimental errors can be classified as systematic errors or random errors. Systematic errors affect accuracy and can result from faulty instruments, while random errors affect precision and arise from unpredictable fluctuations. The document also discusses ways to quantify and describe experimental errors, including percent error, percent difference, mean, and significant figures. Understanding experimental errors is important for analyzing measurement uncertainties and improving experimental design.15694598371.Measurment.pdf

15694598371.Measurment.pdfKhalil Alhatab

╠²

This document provides an overview of measurement and instrumentation topics. It defines measurement as the act of comparing an unknown quantity to a standard. Instruments are defined as devices used to determine the value of a quantity, while instrumentation refers to using instruments to measure properties in industrial processes. The document discusses types of instruments, including active vs passive, as well as different methods and standards used for measurement. It also covers sources of error in measurement, such as systematic, random, alignment, and parallax errors.2.pptx

2.pptxDepartment of Economics, Entrepreneurship and Business Administration, SumDU

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur when making measurements. It categorizes errors as either random or systematic. Random errors are statistical fluctuations that average out with more observations, while systematic errors are reproducible inaccuracies always in the same direction. Sources of error discussed include incomplete definitions, failing to account for factors, environmental factors, instrument resolution, calibration issues, zero offsets, physical variations, parallax, instrument drift, lag times, hysteresis, and personal errors. The key is to identify sources of error, minimize them when possible, and account for remaining errors in data analysis.Measurements and-sources-of-errors1

Measurements and-sources-of-errors1Vikash Kumar

╠²

There are two categories of measurement errors: systematic errors, which are consistent and repeatable, and random errors, which produce inconsistent scatter in measurements. Systematic errors can be caused by calibration issues, loading effects, defective equipment, or human biases. Random errors result from unpredictable fluctuations and limit measurement precision. Sources of error also include zero offset, nonlinearity, sensitivity problems, finite resolution, environmental factors, and issues with reading techniques, instrument loading, supports, dirt, vibrations, metallurgy, contacts, deflection, looseness, gauge wear, location, contact quality, and stylus impression. Careful consideration of error sources is important for obtaining accurate measurements.Error and its types

Error and its typesAvinash Navin

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur in measurements and experiments. It outlines gross errors which are due to blunders, computational mistakes, or chaotic errors. Systematic errors include constructional errors in instruments, determination errors from adjustments, and environmental errors. Random errors cannot be predicted and are due to factors like noise or fatigue. The document provides examples of each type of error and their sources to help understand measurement limitations and improve experimental design.146056297 cc-modul

146056297 cc-modulhomeworkping3

╠²

homework help,online homework help,online tutors,online tutoring,research paper help,do my homework,

https://www.homeworkping.com/Measurements and-sources-of-errors1

Measurements and-sources-of-errors1Vikash Kumar

╠²

This document discusses measurement and sources of error. It defines measurement as determining size, quantity, or degree of something. Primary measurements include length, angle, and curvature. Measurements have standard units like meters and kilograms. Methods of measurement are direct comparison to standards or indirect comparison. Measuring instruments include tools for angles, lengths, surfaces, and deviations. Errors are differences between true and measured values. There are systematic errors that are consistent and random errors that are inconsistent and cause scatter. Sources of error include calibration, loading, environment, reading, and vibrations.CAE344 ESA UNIT I.pptx

CAE344 ESA UNIT I.pptxssuser7f5130

╠²

This document provides an overview of the course objectives and content for an experimental stress analysis course. The main objectives are:

1. To understand techniques for measuring displacements, stresses, and strains in structural components using strain gauges, photoelasticity, and non-destructive testing methods.

2. To familiarize students with different types of strain gauges, instrumentation systems for strain gauges, and photoelasticity stress analysis techniques.

3. To cover the basics of mechanical measurements, electrical resistance strain gauges, rosette strain gauges, and analyze experimental data through statistical methods.

The course will examine measurement systems, error analysis, contact and non-contact extensometers, electrical and opticalLecture 04: Errors During the Measurement Process

Lecture 04: Errors During the Measurement ProcessTaimoor Muzaffar Gondal

╠²

Gross errors are caused by mistake in using instruments or meters, calculating measurement and recording data results.

The best example of these errors is a person or operator reading pressure gage 1.01N/m2 as 1.10N/m2.

This may be the reason for gross errors in the reported data, and such errors may end up in the calculation of the final results, thus deviating results.Types of Error in Mechanical Measurement & Metrology (MMM)

Types of Error in Mechanical Measurement & Metrology (MMM)Amit Mak

╠²

The document discusses various types of errors that can occur in mechanical measurement and metrology. It outlines 11 types of errors: gross, systematic, instrument, environmental, observation, alignment, elastic deformation, dirt, contact, parallax, and random errors. For each error type, it provides a definition and examples to explain the source and nature of the error. The goal is to bring awareness to common errors that can impact measurements so they can be avoided or accounted for.Science enginering lab report experiment 1 (physical quantities aand measurem...

Science enginering lab report experiment 1 (physical quantities aand measurem...Q Hydar Q Hydar

╠²

This document discusses sources of error in measurement and the importance of accuracy. It explains that random errors can cause inconsistent readings and averaging repeated measurements can reduce these errors. Common sources of error include instrument errors, non-linear relationships in instruments, errors from reading scales incorrectly, environmental factors, and human errors. Taking the average of multiple readings eliminates random variations between readings and provides a more accurate result.Chapter1ccccccccccccxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx.pdf

Chapter1ccccccccccccxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx.pdfhalilyldrm13

╠²

gdfzcxcczzzzzzzccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccczzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz4.13 pdf

4.13 pdfDamon Clarke

╠²

This document discusses estimating the margin of error for measurements. It explains that all measurements have some uncertainty due to slight deviations from the true value. This uncertainty is represented as the measured value plus or minus the error. The error depends on the precision of the measuring instrument. For example, if a baseball bat is measured to be 1.34m with precision to the nearest 0.01m, the error is ┬▒0.005m. The document also describes the two types of errors in measurements - random errors, which can be reduced but not eliminated, and systematic errors, which can be eliminated.Measurement erros

Measurement erroschakrimvn

╠²

This document discusses types of errors in measurement. There are three main types of errors: gross errors due to mistakes, systematic errors that cause consistent deviations, and random errors from unpredictable factors. Accuracy refers to the deviation from the true value, while precision refers to the consistency of repeated measurements. Calibration compares instruments to standards to determine accuracy and uncertainty. Error analysis evaluates experimental data to identify errors and validate results.Module 1 mmm 17 e46b

Module 1 mmm 17 e46bD N ROOPA

╠²

This document provides an overview of mechanical measurements and metrology. It discusses key concepts like accuracy, precision, types of errors in measurement, calibration, standards, and classification of measuring instruments. The objectives of metrology are outlined as ensuring measuring instruments are adequate and maintained through calibration. Factors affecting measurement accuracy are explored including the standard, workpiece, instrument, operator, and environment. Common methods of measurement and classification of instruments are also summarized.Errors in pharmaceutical analysis

Errors in pharmaceutical analysis Bindu Kshtriya

╠²

Errors in pharmaceutical analysis can be determinate (systematic) or indeterminate (random). Determinate errors are caused by faults in procedures or instruments and cause results to consistently be too high or low. Sources include improperly calibrated equipment, impure reagents, and analyst errors. Indeterminate errors are random and unavoidable, arising from limitations of instruments. Accuracy refers to closeness to the true value, while precision refers to reproducibility. Systematic errors can be minimized by calibrating equipment, analyzing standards, using independent methods, and blank determinations.Sources of Errors.pptx

Sources of Errors.pptxhepzijustin

╠²

The document discusses sources of errors in measurement. It identifies several potential sources including faulty instrument design, insufficient knowledge of the quantity being measured, lack of instrument maintenance, irregularities in the measured quantity, unskilled instrument operation, design limitations, and environmental factors like temperature changes. The types of errors are also categorized as gross errors from carelessness, systematic errors from instrument shortcomings and characteristics, and random errors. Methods to reduce errors include taking multiple readings, instrument calibration, recognizing systematic error causes, and controlling environmental conditions.Errors in measurement

Errors in measurementGAURAVBHARDWAJ160

╠²

This document discusses errors in measurement and different types of errors. It explains that there are five main elements that can cause errors: standards, work pieces, instruments, persons, and environment. There are three types of errors: systematic errors, which occur due to imperfections and are of fixed magnitude; random errors, which occur irregularly; and statistical analysis can be used to analyze random errors through calculations of mean, range, deviation, and standard deviation. Systematic errors include instrumental errors from faulty instruments, environmental errors from external conditions, and observational errors from human factors like parallax.Unit II: Design of Static Equipment Foundations

Unit II: Design of Static Equipment FoundationsSanjivani College of Engineering, Kopargaon

╠²

Design of Static Equipment, that is vertical vessels foundation.More Related Content

Similar to Presentation Instrumentation and Quality Control.pptx (20)

15694598371.Measurment.pdf

15694598371.Measurment.pdfKhalil Alhatab

╠²

This document provides an overview of measurement and instrumentation topics. It defines measurement as the act of comparing an unknown quantity to a standard. Instruments are defined as devices used to determine the value of a quantity, while instrumentation refers to using instruments to measure properties in industrial processes. The document discusses types of instruments, including active vs passive, as well as different methods and standards used for measurement. It also covers sources of error in measurement, such as systematic, random, alignment, and parallax errors.2.pptx

2.pptxDepartment of Economics, Entrepreneurship and Business Administration, SumDU

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur when making measurements. It categorizes errors as either random or systematic. Random errors are statistical fluctuations that average out with more observations, while systematic errors are reproducible inaccuracies always in the same direction. Sources of error discussed include incomplete definitions, failing to account for factors, environmental factors, instrument resolution, calibration issues, zero offsets, physical variations, parallax, instrument drift, lag times, hysteresis, and personal errors. The key is to identify sources of error, minimize them when possible, and account for remaining errors in data analysis.Measurements and-sources-of-errors1

Measurements and-sources-of-errors1Vikash Kumar

╠²

There are two categories of measurement errors: systematic errors, which are consistent and repeatable, and random errors, which produce inconsistent scatter in measurements. Systematic errors can be caused by calibration issues, loading effects, defective equipment, or human biases. Random errors result from unpredictable fluctuations and limit measurement precision. Sources of error also include zero offset, nonlinearity, sensitivity problems, finite resolution, environmental factors, and issues with reading techniques, instrument loading, supports, dirt, vibrations, metallurgy, contacts, deflection, looseness, gauge wear, location, contact quality, and stylus impression. Careful consideration of error sources is important for obtaining accurate measurements.Error and its types

Error and its typesAvinash Navin

╠²

This document discusses different types of errors that can occur in measurements and experiments. It outlines gross errors which are due to blunders, computational mistakes, or chaotic errors. Systematic errors include constructional errors in instruments, determination errors from adjustments, and environmental errors. Random errors cannot be predicted and are due to factors like noise or fatigue. The document provides examples of each type of error and their sources to help understand measurement limitations and improve experimental design.146056297 cc-modul

146056297 cc-modulhomeworkping3

╠²

homework help,online homework help,online tutors,online tutoring,research paper help,do my homework,

https://www.homeworkping.com/Measurements and-sources-of-errors1

Measurements and-sources-of-errors1Vikash Kumar

╠²

This document discusses measurement and sources of error. It defines measurement as determining size, quantity, or degree of something. Primary measurements include length, angle, and curvature. Measurements have standard units like meters and kilograms. Methods of measurement are direct comparison to standards or indirect comparison. Measuring instruments include tools for angles, lengths, surfaces, and deviations. Errors are differences between true and measured values. There are systematic errors that are consistent and random errors that are inconsistent and cause scatter. Sources of error include calibration, loading, environment, reading, and vibrations.CAE344 ESA UNIT I.pptx

CAE344 ESA UNIT I.pptxssuser7f5130

╠²

This document provides an overview of the course objectives and content for an experimental stress analysis course. The main objectives are:

1. To understand techniques for measuring displacements, stresses, and strains in structural components using strain gauges, photoelasticity, and non-destructive testing methods.

2. To familiarize students with different types of strain gauges, instrumentation systems for strain gauges, and photoelasticity stress analysis techniques.

3. To cover the basics of mechanical measurements, electrical resistance strain gauges, rosette strain gauges, and analyze experimental data through statistical methods.

The course will examine measurement systems, error analysis, contact and non-contact extensometers, electrical and opticalLecture 04: Errors During the Measurement Process

Lecture 04: Errors During the Measurement ProcessTaimoor Muzaffar Gondal

╠²

Gross errors are caused by mistake in using instruments or meters, calculating measurement and recording data results.

The best example of these errors is a person or operator reading pressure gage 1.01N/m2 as 1.10N/m2.

This may be the reason for gross errors in the reported data, and such errors may end up in the calculation of the final results, thus deviating results.Types of Error in Mechanical Measurement & Metrology (MMM)

Types of Error in Mechanical Measurement & Metrology (MMM)Amit Mak

╠²

The document discusses various types of errors that can occur in mechanical measurement and metrology. It outlines 11 types of errors: gross, systematic, instrument, environmental, observation, alignment, elastic deformation, dirt, contact, parallax, and random errors. For each error type, it provides a definition and examples to explain the source and nature of the error. The goal is to bring awareness to common errors that can impact measurements so they can be avoided or accounted for.Science enginering lab report experiment 1 (physical quantities aand measurem...

Science enginering lab report experiment 1 (physical quantities aand measurem...Q Hydar Q Hydar

╠²

This document discusses sources of error in measurement and the importance of accuracy. It explains that random errors can cause inconsistent readings and averaging repeated measurements can reduce these errors. Common sources of error include instrument errors, non-linear relationships in instruments, errors from reading scales incorrectly, environmental factors, and human errors. Taking the average of multiple readings eliminates random variations between readings and provides a more accurate result.Chapter1ccccccccccccxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx.pdf

Chapter1ccccccccccccxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx.pdfhalilyldrm13

╠²

gdfzcxcczzzzzzzccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccccczzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz4.13 pdf

4.13 pdfDamon Clarke

╠²

This document discusses estimating the margin of error for measurements. It explains that all measurements have some uncertainty due to slight deviations from the true value. This uncertainty is represented as the measured value plus or minus the error. The error depends on the precision of the measuring instrument. For example, if a baseball bat is measured to be 1.34m with precision to the nearest 0.01m, the error is ┬▒0.005m. The document also describes the two types of errors in measurements - random errors, which can be reduced but not eliminated, and systematic errors, which can be eliminated.Measurement erros

Measurement erroschakrimvn

╠²

This document discusses types of errors in measurement. There are three main types of errors: gross errors due to mistakes, systematic errors that cause consistent deviations, and random errors from unpredictable factors. Accuracy refers to the deviation from the true value, while precision refers to the consistency of repeated measurements. Calibration compares instruments to standards to determine accuracy and uncertainty. Error analysis evaluates experimental data to identify errors and validate results.Module 1 mmm 17 e46b

Module 1 mmm 17 e46bD N ROOPA

╠²

This document provides an overview of mechanical measurements and metrology. It discusses key concepts like accuracy, precision, types of errors in measurement, calibration, standards, and classification of measuring instruments. The objectives of metrology are outlined as ensuring measuring instruments are adequate and maintained through calibration. Factors affecting measurement accuracy are explored including the standard, workpiece, instrument, operator, and environment. Common methods of measurement and classification of instruments are also summarized.Errors in pharmaceutical analysis

Errors in pharmaceutical analysis Bindu Kshtriya

╠²

Errors in pharmaceutical analysis can be determinate (systematic) or indeterminate (random). Determinate errors are caused by faults in procedures or instruments and cause results to consistently be too high or low. Sources include improperly calibrated equipment, impure reagents, and analyst errors. Indeterminate errors are random and unavoidable, arising from limitations of instruments. Accuracy refers to closeness to the true value, while precision refers to reproducibility. Systematic errors can be minimized by calibrating equipment, analyzing standards, using independent methods, and blank determinations.Sources of Errors.pptx

Sources of Errors.pptxhepzijustin

╠²

The document discusses sources of errors in measurement. It identifies several potential sources including faulty instrument design, insufficient knowledge of the quantity being measured, lack of instrument maintenance, irregularities in the measured quantity, unskilled instrument operation, design limitations, and environmental factors like temperature changes. The types of errors are also categorized as gross errors from carelessness, systematic errors from instrument shortcomings and characteristics, and random errors. Methods to reduce errors include taking multiple readings, instrument calibration, recognizing systematic error causes, and controlling environmental conditions.Errors in measurement

Errors in measurementGAURAVBHARDWAJ160

╠²

This document discusses errors in measurement and different types of errors. It explains that there are five main elements that can cause errors: standards, work pieces, instruments, persons, and environment. There are three types of errors: systematic errors, which occur due to imperfections and are of fixed magnitude; random errors, which occur irregularly; and statistical analysis can be used to analyze random errors through calculations of mean, range, deviation, and standard deviation. Systematic errors include instrumental errors from faulty instruments, environmental errors from external conditions, and observational errors from human factors like parallax.Recently uploaded (20)

Unit II: Design of Static Equipment Foundations

Unit II: Design of Static Equipment FoundationsSanjivani College of Engineering, Kopargaon

╠²

Design of Static Equipment, that is vertical vessels foundation.Sachpazis: Foundation Analysis and Design: Single Piles

Sachpazis: Foundation Analysis and Design: Single PilesDr.Costas Sachpazis

╠²

Žü. ╬ÜŽÄŽāŽä╬▒Žé ╬Ż╬▒ŽćŽĆ╬¼╬Č╬ĘŽé: Foundation Analysis and Design: Single Piles

Welcome to this comprehensive presentation on "Foundation Analysis and Design," focusing on Single PilesŌĆöStatic Capacity, Lateral Loads, and Pile/Pole Buckling. This presentation will explore the fundamental concepts, equations, and practical considerations for designing and analyzing pile foundations.

We'll examine different pile types, their characteristics, load transfer mechanisms, and the complex interactions between piles and surrounding soil. Throughout this presentation, we'll highlight key equations and methodologies for calculating pile capacities under various conditions.How to Make an RFID Door Lock System using Arduino

How to Make an RFID Door Lock System using ArduinoCircuitDigest

╠²

Learn how to build an RFID-based door lock system using Arduino to enhance security with contactless access control.Air pollution is contamination of the indoor or outdoor environment by any ch...

Air pollution is contamination of the indoor or outdoor environment by any ch...dhanashree78

╠²

Air pollution is contamination of the indoor or outdoor environment by any chemical, physical or biological agent that modifies the natural characteristics of the atmosphere.

Household combustion devices, motor vehicles, industrial facilities and forest fires are common sources of air pollution. Pollutants of major public health concern include particulate matter, carbon monoxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide. Outdoor and indoor air pollution cause respiratory and other diseases and are important sources of morbidity and mortality.

WHO data show that almost all of the global population (99%) breathe air that exceeds WHO guideline limits and contains high levels of pollutants, with low- and middle-income countries suffering from the highest exposures.

Air quality is closely linked to the earthŌĆÖs climate and ecosystems globally. Many of the drivers of air pollution (i.e. combustion of fossil fuels) are also sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Policies to reduce air pollution, therefore, offer a win-win strategy for both climate and health, lowering the burden of disease attributable to air pollution, as well as contributing to the near- and long-term mitigation of climate change.

Mathematics behind machine learning INT255 INT255__Unit 3__PPT-1.pptx

Mathematics behind machine learning INT255 INT255__Unit 3__PPT-1.pptxppkmurthy2006

╠²

Mathematics behind machine learning INT255 UNIT 1FUNDAMENTALS OF OPERATING SYSTEMS.pptx

UNIT 1FUNDAMENTALS OF OPERATING SYSTEMS.pptxKesavanT10

╠²

UNIT 1FUNDAMENTALS OF OPERATING SYSTEMS.pptxHow Engineering Model Making Brings Designs to Life.pdf

How Engineering Model Making Brings Designs to Life.pdfMaadhu Creatives-Model Making Company

╠²

This PDF highlights how engineering model making helps turn designs into functional prototypes, aiding in visualization, testing, and refinement. It covers different types of models used in industries like architecture, automotive, and aerospace, emphasizing cost and time efficiency.Lecture -3 Cold water supply system.pptx

Lecture -3 Cold water supply system.pptxrabiaatif2

╠²

The presentation on Cold Water Supply explored the fundamental principles of water distribution in buildings. It covered sources of cold water, including municipal supply, wells, and rainwater harvesting. Key components such as storage tanks, pipes, valves, and pumps were discussed for efficient water delivery. Various distribution systems, including direct and indirect supply methods, were analyzed for residential and commercial applications. The presentation emphasized water quality, pressure regulation, and contamination prevention. Common issues like pipe corrosion, leaks, and pressure drops were addressed along with maintenance strategies. Diagrams and case studies illustrated system layouts and best practices for optimal performance.How to Build a Maze Solving Robot Using Arduino

How to Build a Maze Solving Robot Using ArduinoCircuitDigest

╠²

Learn how to make an Arduino-powered robot that can navigate mazes on its own using IR sensors and "Hand on the wall" algorithm.

This step-by-step guide will show you how to build your own maze-solving robot using Arduino UNO, three IR sensors, and basic components that you can easily find in your local electronics shop.Lessons learned when managing MySQL in the Cloud

Lessons learned when managing MySQL in the CloudIgor Donchovski

╠²

Managing MySQL in the cloud introduces a new set of challenges compared to traditional on-premises setups, from ensuring optimal performance to handling unexpected outages. In this article, we delve into covering topics such as performance tuning, cost-effective scalability, and maintaining high availability. We also explore the importance of monitoring, automation, and best practices for disaster recovery to minimize downtime.Turbocor Product and Technology Review.pdf

Turbocor Product and Technology Review.pdfTotok Sulistiyanto

╠²

High Efficiency Chiller System in HVACautonomous vehicle project for engineering.pdf

autonomous vehicle project for engineering.pdfJyotiLohar6

╠²

autonomous vehicle project for engineeringPresentation Instrumentation and Quality Control.pptx

- 1. MIRPUR UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (MUST), MIRPUR DEPARMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING

- 2. Group No 13 Name Roll No Ahsan Farooq FA20-BME-005 Ali Munir FA20-BME-006 Khawaja Basharat Maqbool FA20-BME-016

- 4. Introduction ’āśDefinition of Measurement ’āśImportance of Accurate Measurements ’āśErrors in Measurement

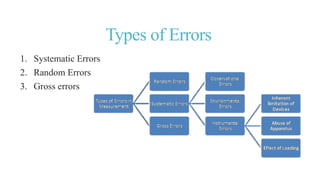

- 5. Types of Errors 1. Systematic Errors 2. Random Errors 3. Gross errors

- 6. Systematic Errors ’āś Result from consistent flaws in the measurement system. ’āś Can be caused by equipment calibration, faulty procedure adopted by person making measurement, or environmental factors. ’āś Often lead to inaccuracies in all measurements taken using the flawed system.

- 7. Systematic Errors Example: If a balance scale consistently shows a reading even when nothing is placed on it, there's a systematic error.

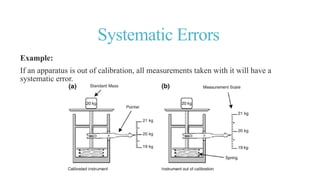

- 8. Systematic Errors Example: If an apparatus is out of calibration, all measurements taken with it will have a systematic error.

- 9. Systematic Errors Reduction of Systematic Errors: ’āśEnsure that all measurement instruments are properly calibrated and standardized. ’āśKeep your measurement instruments well-maintained and in good working condition. ’āśEnsure that instruments have been zeroed properly before making measurements.

- 10. Random Errors ’āśDue to unpredictable variations in measurement conditions. ’āśCaused by factors like noise, fluctuations in environmental conditions, and human limitations. ’āśAffect the precision of measurements rather than their accuracy.

- 11. Random Errors Example: When measuring the weight of an object using a balance scale, random air currents in the environment can cause the object to sway slightly, leading to fluctuations in the measured weight.

- 12. Random Errors Example: When weighing yourself on a scale, you position yourself slightly differently each time.

- 13. Random Errors Causes of Random Errors: ’āś External noise sources (electromagnetic interference, vibration, etc.). ’āś Imperfections in the measurement instrument. ’āś Variability in the phenomenon being measured. Reduction of Random Errors: ’āś Repeated measurements and calculating averages. ’āś Statistical analysis to quantify the uncertainty. ’āś Proper shielding and isolation of measurement setups

- 14. Gross errors ’āśThese errors are caused by mistake in using instruments, recording data and calculating results. ’āśCause by human mistakes in reading/using instruments. ’āśMay also occur due to incorrect adjustment of the instrument and the computational mistakes. ’āśCannot be treated mathematically. ’āśCannot eliminate but can minimize.

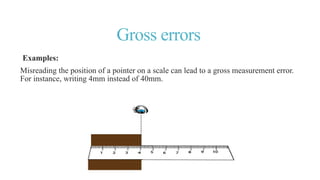

- 15. Gross errors Examples: Misreading the position of a pointer on a scale can lead to a gross measurement error. For instance, writing 4mm instead of 40mm.

- 16. Gross errors Examples: Miswriting or mistyping a numerical value, decimal point, or unit can result in substantial measurement discrepancies. For instance, a person may read a pressure gauge indicating 1.01 Pa as 10.1 Pa.

- 17. Gross errors Reduction of Gross Errors: ’āśEnsure that the measurement procedures and techniques are correct and aligned with the standard methods. ’āśProper care should be taken in reading, recording the data. ’āśBy increasing the number of experimenters, we can reduce the gross errors.

- 18. References ’āśTYPES OF ERROR Types of static error Gross error/human error published by Jonah Parrish https://slideplayer.com/slide/13549419/ ’āśWhat are gross errors? Explain with its cause.- BYJU'S: https ://byjus.com/question-answer/what-are-gross-errors-explain-with-its-cause/

- 19. Thanks