The BOMA Project by David DuChemine

- 1. As recurring drought devastates their livestock, the pastoral nomads of northern Kenya are learning new ways to make a living. Photographs by David duChemin Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org the boma project Working Solutions to Climate Change Malawan Lejalle and her daughter in the nomadic village of Ndikir, near the family hut and chicken coop.

- 2. As prolonged drought destroys the grazing terrain, warriors take the herds on long trips in search of forage. The women and children are left behind without cattle, their traditional source of food and income. “My husband does not know if he will find us alive when he comes home,” says Malawan Lejalle (photo at left), who leads a three-woman business group that sells food staples—such as beans, tea and sugar—to residents in Ndikir. “But the last time he returned, he found his eight children doing well.” In addition to generating income for food, her business is using its savings to send 17 local children to secondary school. Above: Malawan (in green) counts profits with partner Algoya Basele. Northern Kenya is a remote and neglected region that suffers from extreme poverty and hunger. Severe droughts now threaten the main source of food and income—livestock herding—that has sustained the pastoral nomads here for centuries. Since January 2009, The BOMA Project has been helping residents to start small businesses and earn a sustainable income through the Rural Entrepreneur Access Project (REAP), which offers a seed capital grant, training in business skills and savings, and two years of mentoring to groups of three women. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

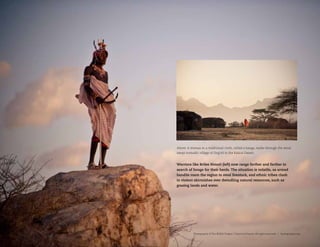

- 3. Above: A woman in a traditional cloth, called a kanga, walks through the wind-swept nomadic village of Ong’eli in the Kaisut Desert. Warriors like Brilee Rimoti (left) now range farther and farther in search of forage for their herds. The situation is volatile, as armed bandits roam the region to steal livestock, and ethnic tribes clash in violent skirmishes over dwindling natural resources, such as grazing lands and water. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 4. Drought has made life harder in many ways. Children walk long distances to collect kindling for the family cooking fires (above), while many livestock—the nomad’s source of sustenance for centuries—have died during the driest condi-tions in decades. Hunger and malnutrition are at critical levels across the region. Left: Warrior Long’erua Letorre brings his cattle home to Ndera village. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 5. The traditional nomadic diet relied on cattle milk and blood as the main source of nutrition. As the warriors travel in search of grazing terrain, the women are left to themselves, with no money and no food. Maize flour and cooking oil, often delivered as famine relief by aid organizations, have become the new staples, and sweetened tea is considered a meal. Above: Nayong Lomurut and Ntojoni Ngosoni serve their children sweet tea for breakfast in front of a family hut. School was not a priority in traditional nomadic culture, but more families are now enrolling their children: Primary school is free, and each child receives a mid-day meal. Students walk as far as 20 kilometers to attend. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 6. Because many schools do not have a building, teachers often gather under the shade of trees and use a single blackboard. In this photo: Classes at St. Dominique Savior School in Manyatta Lengina village. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 7. The REAP program targets women. Studies indicate that economically empowering women—the “poorest of the poor”—is an effective way to fight poverty in the develop-ing world. Above: Arbe Wario sells traditional water gourds to visitors and aid workers who frequently travel through her village of Loiyangalani. Right: Halhalo Barmin lives in Goob Barmin, where she and her business partners run a small food kiosk. Savings from the business allowed her to loan her brother money, which provided life-saving medical care for one of his children. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 8. Halima Arbele (above) is a BOMA Village Mentor. Mentors are respected local residents who have professional experience; Halima attended secondary school and runs her own small shop. Mentors work closely with each business to ensure success. In this photo, Halima meets with a REAP group for a progress report; she walked 15 kilometers from her home to the nomadic village of Obregebo, where the women have opened a kiosk. Left: BOMA entrepreneurs sell potatoes at the market in Loglogo, one of the few areas in the semi-arid Laisamis District where it’s possible to raise crops. The women bring their produce to market every day of the week, except Sundays. photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 9. BOMA mentor John Lesas reviews a record book with a business group in the village of Ngurunit. John is a highly regarded primary school teacher and community leader in the village. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 10. Beading is a traditional nomadic skill; the women in this Laisamis village business group sell their products to travelers who pass through northern Kenya on the Pan-African Highway. Laisamis District—an area larger than the country of Rwanda—has only two medical clinics and no paved roads, post offices or banks. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 11. Three BOMA entrepreneurs—Gumato Lomurut, Ntelengon Lamut and Kehsimo Eisemkelle— cross the Kaisut Desert on the way from their nomadic settlement, Nemerai, to the settled village of Korr. They buy food and supplies from a wholesaler in Korr, and then sell the goods in their village kiosk. They used to haul the supplies home on their backs; now they can afford to hire mules. Sometimes they also hire a warrior to protect them from bandits and wild animals. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 12. 110 of BOMA’s 720 micro-enterprises operate near the village of Loiyangalani on Lake Turkana, the world’s largest desert lake and a UNESCO World Heritage site. Many of the busi-ness groups buy fish along the shoreline and resell it—dried or fresh—for retail prices at market. Right: Etelej Erumu and Nakorodio Esimit stack dried fish for resale. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 13. The BOMA micro-savings program teaches participants the importance of savings, helps REAP groups to establish mentored savings and loans associations, and facilitates access to secure savings instruments, such as lockboxes, mobile-phone banking, and formal banking (where available). Above: A REAP group in Kamboe that sells inexpensive mobile phones. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 14. Raphaela Mpiraon Neepe is the only educated woman in the village of Kamboe; she attended secondary school and has worked for several NGOs. As a BOMA Village Mentor, she meets with REAP participants to discuss their business and review record books and savings. “BOMA is helping women,” she says. “The participants are benefiting through their businesses.”

- 15. Each business supports three women and an average of fifteen children; an impact survey showed that REAP parti-cipants use the income to pay for food, medical care and school supplies for their families. Above: Adowto Isandab used income from her business to buy school supplies for her son, Schola. Right: Sabthio Wambile feeds a child by lantern light. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org

- 16. The BOMA Project works to improve the lives of the marginalized residents of northern Kenya through economic empowerment, education, advocacy and the training of a new generation of ethical, entrepreneurial leaders. 802.231.2542 www.bomaproject.org info@bomaproject.org Nayong Lomurut with her daughter, Ntimiran. Photography © The BOMA Project / David duChemin. All rights reserved. | bomaproject.org