URINARY TRACT INFECTION IN CHILDREN 2.pptx

- 1. BY DR FUAD ALSHARABI PEDIATRIC CONSULTANT

- 2. PREVALENCE AND ETIOLOGY ’éŚ UTIs commonly occur in children of all ages. ’éŚ Most common in chidren under 1years of age. ’éŚ MALE :FEMALE RATIO 2.4:5.4 in first year of life. ’éŚ Beyond 1-2 years there is female preponderance 1:10 male female ratio. ’éŚ UTIs mutch more common in uncircumsed male.

- 4. PREVALENCE AND ETIOLOGY ’éŚ UTIs caused primarly by colonic bacteria . ’éŚ Escerichia coli caused 54-67 % of all UTIs.followed by klebsiella spp.and proteus spp, Enterococus,and pseudomonase. ’éŚ Other Bacteria include staphlococus saprophyticus ,Group B streptococus. ’éŚ Less common staphylococus aureus,candida spp and salmonela spp ’éŚ UTIs have been considred a risk factor for the development of renal insufficiensy or end- stage of renal disease.

- 5. CLINICAL MANIFESTATION AND CLASSIFICATION ’éŚ Two form of UTI pyelonephritis and cystitis. ’éŚ PYELONEPHRITIS characterized by any or all the following; ’éŚ BACK OR FLANK PAIN ’éŚ FEVER ’éŚ MALAISE ’éŚ NAUSEA ’éŚ VOMITING ’éŚ DIARRHEA

- 6. CLINICAL MANIFESTATION AND CLASSIFICATION ’éŚ Neobrns can show nonspecific symptoms such as; ’éŚ POOR FEEDING ’éŚ IRRITABILITY ’éŚ JAUNDICE ’éŚ WEIGHT LOSS ’éŚ Pyelonephritis is the most common seriuse pacterial infectin in an infant younger than 24 month of age have fever whithout obvius focus.

- 7. CLINICAL MANIFESTATION AND CLASSIFICATION ’éŚ Involvement of renal parenchyma is term acute pyelonephritis. ’éŚ Pylitis no parenchymal involvment. ’éŚ Aute lobar nephrona is alocalized renal parenchymal mass caused by acute focal infection without lequefacton. Fever and flank pain and other manifestations of pyelonephritis. ’éŚ Renal abcess typically occurs followed hematogenous spreed of s.aureus or pyelonephritic infection. ’éŚ PERINEPHRIC ABSCESS ’éŚ XANTHOGRANOLOMATOUS PYELONEPHRITIS

- 9. CYSTITIS ’éŚ THERE IS ONLY BLADDER INVOLVMENT ’éŚ DYSURIA ’éŚ URGENSY ’éŚ FREQUENSY ’éŚ SUPRAPUBIC PAIN ’éŚ INCONTINENCE ’éŚ MALODORS URINE ’éŚ ACUTE HEMORRHAGIC CYSTITIS ’éŚ EOSINOPHILIC CYSTITIS

- 10. PATHOGENISIS AND PATHOLOGY ’éŚ Nearly all UTIs are ascending infection . ’éŚ Bacteria arise from the fecal flora clonized the perneum,and enter the bladder via the urethra. ’éŚ Rarely renal infection occur by hematogenuse spread as in endocarditis or in some bacterimic neonate . ’éŚ CHILDREN OF ANY AGE WITH FEBRILE UTI CAN HAVE ACUTE PYELONEPHRITIS AND SUBSEQUENT RENAL SCARING

- 11. RISK FACTOR FOR UTI ’éŚ VUR ’éŚ FEMAL GENDER ’éŚ UNCIRCUMCISE MALE ’éŚ SOURSE OF EXTERNAL IRRITATION ’éŚ BOWEL- BLODDER DYSFUNCTION ’éŚ OBSTRUCTIVE UROPATHY ’éŚ UROGENIC BLODDER DYSFUNCTION ’éŚ CONSTIPATION ’éŚ ANATOMIC ABNORMALITIS ’éŚ SEXUAL ACTIVITY

- 12. DIAGNOSISE ’éŚ SYMPTOMS ’éŚ FINDIG OF URINALYSISE ’éŚ URINE CULTURE ’éŚ Urine culture remains the gold standard for diagnosing

- 13. IMAGING FINDING ’éŚ IS NOT NEEDED TO MAKE THE CLINICAL DIAGNOSISE OF UTI OR PYELONEPHRITIS ’éŚ ULTRASOUND THE FIRST LINE TYPE OF IMAGING ’éŚ CT SCAN MORE SENSITIVE AND SPECIFIC FOR LOPAR NEPHRONIA

- 14. LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS ’éŚ The presence of Ōēź 5 white blood cells per high power field in centrifuged urine or Ōēź 10 white blood cells as detected by hemocytometer in uncentrifuged urine, respectively, is the gold standard for pyuria . ’éŚ However, pyuria is not diagnostic of UTI . Pyuria has a specificity of approximately 81% and sensitivity of 73% . ’éŚ Sterile pyuria can be associated with infection due to anaerobic bacteria, tuberculosis, viral pathogens, chemical or allergic inflammation, cervical or vaginal secretion, Kawasaki disease, crystalluria,appendicitis, regional enteritis, glomerulonephritis, and interstitial nephritis .

- 15. LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS ’éŚ Conversely, the absence of pyuria on a single specimen does not rule out UTI. ’éŚ Serial urinalysis in patients with UTI eventually shows pyuria. ’éŚ Dipstick tests are inexpensive, convenient, readily available, and useful for diagnosis of UTI. ’éŚ The leukocyte esterase dipstick test demonstrates the presence of pyuria by histochemical methods that detect this enzyme in neutrophils . ’éŚ Leukocyte esterase is also present even if leukocytes are lysed.

- 16. LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS ’éŚ Neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated serum C-reactive protein, and white blood cell casts in the urinary sediment are suggestive of acute pyelonephritis. ’éŚ Children with very high serum procalcitonin levels during UTI are more likely to have acute pyelonephritis ’éŚ A meta-analysis of 18 studies involving 831 children with acute pyelonephritis and 651 children with lower UTI were analyzed . ’éŚ The authors found that a serum procalcitonin cutoff value of 1.0ng/ml provides a good diagnostic value for discriminating acute pyelonephritis from lower UTI. Because of the marked heterogeneity between studies, more intensive studies are necessary before this test can be routinely recommended in the evaluation and management of a child with UTI.

- 17. LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS ’éŚ According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guidelines, the diagnosis of UTI in children 2 to 24 months requires positive dipstick test (leukocyte esterase and/or nitrite test), microscopy positive for pyuria or bacteriuria, and the presence of Ōēź 50,000cfu/ml of a uropathogen in a catheterized or suprapubic aspiration specimen ’éŚ According to the Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) guidelines, a positive dipstick test (leukocyte esterase and/or nitrite) and a positive urine culture of a single uropathogen (Ōēź 100,000cfu/ml in a midstream urine specimen, Ōēź 50,000cfu/ml in a catheterized specimen, and any organism in a suprapubic aspiration specimen) are required for the diagnosis of UTI .

- 18. LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS ’éŚ The European Association of Urology (EAU) / European Society for Paediatric Urology (ESPU) guidelines state that growth of 10,000 or even 1,000cfu/ml of a uropathogen from a catheterized specimen or any counts from a suprapubic aspiration specimen is sufficient to diagnose a UTI . ’éŚ In toilet-trained children, a clean-catch midstream urine specimen rather than a catheterized or a suprapubic aspiration specimen should be submitted for urinalysis and urine culture

- 19. LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS ’éŚ In the work-up of children with UTI, physicians must judiciously utilize imaging studies to minimize exposure of children to radiation. ’éŚ Renal and bladder ultrasonography is the method of choice to image the urinary tract . ’éŚ Ultrasonography is noninvasive, safe, easy to perform, and radiation-free . ’éŚ A renal and bladder ultrasound can define the kidney size, shape and position, echotexture of the renal parenchyma, the presence of duplication and dilatation of the ureters, obstructive uropathy, and structural abnormality of the bladder

- 20. LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS ’éŚ Renal imaging with 99mTc-Dimercaptosuccinic Acid (DMSA) can be used to detect acute pyelonephritis and renal scarring . ’éŚ Decreased renal uptake of the isotope suggests acute pyelonephritis or renal scarring . ’éŚ In addition, a DMSA renal scan can detect majority (> 70%) of children with moderate to severe vesicoureteric reflux ’éŚ The NICE guidelines recommend DMSA renal scan 4 to 6 months after atypical UTI in children under 3 years of age and recurrent UTI in children of any age .

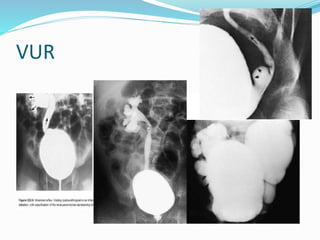

- 21. LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS ’éŚ A voiding cystourethrogram is the preferred screening test for vesicoureteric reflux. ’éŚ This study accurately grades vesicoureteric reflux; identifies posterior urethral valves, ureteroceles, obstructive uropathies, and other abnormalities of the urethra, ureter, and bladder (e.g., bladder diverticuli or trabeculations); and provides clues to the presence of urge syndrome and dysfunctional voiding 25 to 30% of children with UTI have vesicoureteric reflux .

- 22. VUR

- 24. ’éŚ Cystoscopy is indicated in children with severe vesicoureteric reflux, moderate vesicoureteric reflux unresponsive to conservative treatment, suspected duplicated collecting system, ureterocele, urethral obstruction, or neurogenic bladder

- 25. TREATMENT ’éŚ Acute cystitis shoud be treated promptly to prevent possible progression to pyelonephritis ’éŚ If the symptoms are severe ,presumptive treatment is started pending results of the culture ’éŚ If the symptoms are mild or the diagnosise is doubtful treatment can be delay until the results of culture are known.

- 26. TREATMENT ’éŚ In acute febrile UTIs the clinical symptoms of UTI and peylonephritis are difficult to differentiate ’éŚ A COURSE OF ANTIBIOTIC for 7 to 14 days oral or parental ’éŚ Children who are dehydrated ,are vomiting,are unable to drink fluids,have complicated infection,or in who urosepsise is possibility shoud be admittted to hospital for IV rehydration and iv antibiotic therapy. ’éŚ Local antimicrobial sensitivity pattern shoud be considered when selecting emprical antibiotic treatment

- 27. TREATMENT ’éŚ For cystitis trimethoprim ŌĆōsulfamethoxazole Or nitrofurantoin or amoxiciline In acute febrile UTI ceftriaxone 50 mg kg├®24h or cefipime 100 mg├®kg├®24 h or cefotaxime 100-150 mg kg 24h Clinical treatment with fluoroquinolones in children shoud be used with caution becouse of potiential cartilage damage

- 28. TREATMENT ’éŚ The optimal duration of treatment of UTI is controversial . A 2003 Cochrane systematic review of 10 randomized and quasi-randomized controlled studies involving 652 children with lower UTI found no significant difference between 2 to 4 days and 7 to 14 days of oral antibiotic therapy in terms of frequency of positive urine cultures, development of resistant organisms, or recurrence of UTI. ’éŚ A 2012 Cochrane systematic review of 16 randomized and controlled studies involving 1,116 children with lower UTI found that 10 days of antibiotic treatment is more likely to eliminate bacteria from the urine than single-dose therapy.

- 29. TREATMENT ’éŚ unless further studies and more updated systematic review show it otherwise. ’éŚ A 2007 Cochrane review of 23 randomized and quasi randomized controlled studies involving 3,295 children with acute pyelonephritis found no significant difference between oral antibiotic therapy (10 to 14 days) and intravenous antibiotic therapy (3 days) followed by oral antibiotic therapy (10 days) in terms of duration of fever and subsequent persistent renal damage . ’éŚ Similarly, there was a significant difference between intravenous antibiotic therapy (3 to 4 days) followed by oral antibiotic therapy and intravenous antibiotic therapy (7 to 14 days) in terms of persistent renal damage

- 30. CONCLUSION ’éŚ Management of UTI in children can be challenging because symptoms can be vague and nonspecific in young children. ’éŚ A high index of suspicion is essential. ’éŚ UTI should be considered in any child < 2 years presenting with fever. ’éŚ On the one hand, over-diagnosis may lead to unnecessary and potentially invasive testing, unnecessary treatment, and the emergence of bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

- 31. CONCLUSION ’éŚ On the other hand, under-diagnosis and delayed treatment may lead to recurrence and risk for renal scarring which may lead to hypertension and chronic renal failure. ’éŚ Timely and accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment are therefore essential.