Variations of Black Identity

- 1. Shades of Black: An Introduction to Cultural Considerations for African and Caribbean PeopleChakka Reeves, M.Ed.Assistant Dean, Multicultural Education and Outreach Drexel Universitychakka.reeves@drexel.edu Hahnemann PresentationFebruary 26th, 2009

- 2. TerminologyBlack/African AmericanPeople of African descent who are 1st or 1.5th generation or native to the U.S. and CanadaImmigrant BlacksPeople of African descent who are themselves recent immigrants or are the children of recent immigrantsAfricansPeople of African descent who are themselves or whose parents are from an African country, not including: Algeria,Egypt,Libya,Morocco,TunisiaAfro-Caribbeans/ West IndiansPeople of African descent who are themselves or whose parents are from a Caribbean country, not including: Cuba, Dominican Republic, Costa Rica or other Latin American countries

- 3. Presentation ObjectivesIntroduction to Terminology Current Immigration TrendsCulture and Educational AttainmentIdentity Development TheoryImplications for Practices

- 4. Immigrant Blacks in the United StatesThe number of African Americans with recent roots in sub-Saharan Africa nearly tripled during the 1990’sCensus 2000 shows that:Afro-Caribbeans in the United States number over 1.5 millionAfricans number over 600 thousandSource: Logan, J. R., & Deane, G. (2003). Black diversity in metropolitan America: Lewis Mumford Center, University at Albany, State University of New York.

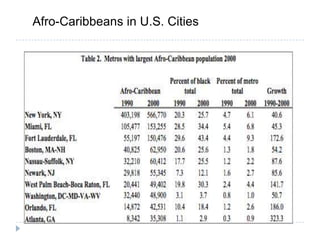

- 5. Immigrant Blacks in the United StatesAfro-Caribbeansare heavily concentrated on the East Coast America’s African population is more geographically dispersed, but is heavily concentrated in the Washington D.C. metro area and New York The majority are from West Africa, particularly Ghana and Nigeria East Africans, including Ethiopians and Somalians, are the second most represented groupSource: Logan, J. R., & Deane, G. (2003). Black diversity in metropolitan America: Lewis Mumford Center, University at Albany, State University of New York.

- 6. Africans in the U.S. by region

- 7. Afro-Caribbeans in U.S. Cities

- 9. Immigrant Blacks in the United StatesAfricans tend to live in neighborhoods with higher median income and education level than African Americans and Afro-CaribbeansAfro-Caribbeans tend to live in neighborhoods with a higher percent homeowners than either African Americans or AfricansSource: Logan, J. R., & Deane, G. (2003). Black diversity in metropolitan America: Lewis Mumford Center, University at Albany, State University of New York.

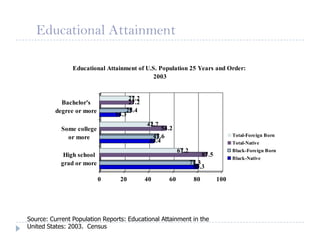

- 11. Educational AttainmentSource: Current Population Reports: Educational Attainment in the United States: 2003. Census

- 12. A study at HarvardRimer and Arenson (2004) report that Harvard University’s African Americans population is eight percent, but two-thirds of these students are West Indian and African immigrants or the children of these immigrants (this number also includes bi-racial children, but to a lesser degree)Source:Rimer, S., & Arenson, K. W. (June 24th,2004). Top Colleges Take More Blacks, But Which Ones? The New York Times.

- 13. Massey, Mooney, Torres and Charles (2007)“Black Immigrants and Black Natives Attending Selective Colleges and Universities in the United States.” Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Freshmen (NLSF), the article looked at a sample of 747 Black students who were of native origin, and 281 who were of immigrant origin, “yielding an overall immigrant percentage of 27 percent” (p.243)

- 14. Academic Achievement and Identity DevelopmentAmong black high school students, positive and realistic views of one’s ethnic identity are linked to:Higher rates of high school completion Higher rates of enrollment in 2 and 4-year institutionsSource:Chavous, T. M., Bernat, D. H., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Caldwell, C. H., Kohn-Wood, L., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2003). Racial Identity and Academic Attainment Among African American Adolescents. Child Development, 74(4), 1076-1090.

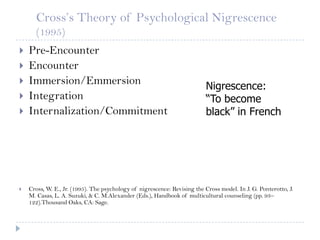

- 16. Cross’s Theory of Psychological Nigrescence(1995)Pre-EncounterEncounterImmersion/EmmersionIntegrationInternalization/CommitmentCross, W. E., Jr. (1995). The psychology of nigrescence: Revising the Cross model. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M.Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 93–122).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Nigrescence: “To become black” in French

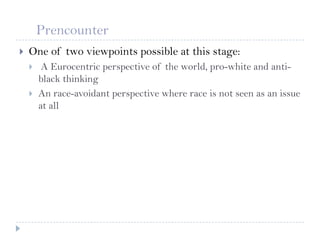

- 17. PrencounterOne of two viewpoints possible at this stage: A Eurocentric perspective of the world, pro-white and anti-black thinkingAn race-avoidant perspective where race is not seen as an issue at all

- 18. EncounterInvolves an event or series of events that create dissonance for the individual, causing them to look at their previous world view more critically Events that trigger movement to this stage may be: Stark and traumatic, such as being called a racial slur or being denied access to something because of raceGradual and positive, such as being a part of an identity-based student group or reading an influential book on a black historical figure, such as Malcolm X.

- 19. Immersion/EmmersionAt this stage, the individual begins to immerse themselves in all things related to black and African cultures and avoid anything EurocentricOne’s blackness at this stage is based on outward appearances,and is insecure

- 20. IntergrationThe exclusive engagement in black/African culture is leveled, and the individual begins to integrate their previous identity into their new worldview

- 21. Internalization/CommittmentIndividuals at this stage have reached another level of their feelings of internalization. Not only are they comfortable of their blackness on an individual level, but they are able to translate these feelings into commitment to a larger Black community and/or an even larger group of marginalized people, racially or otherwise.

- 22. Cross’s Model in S. African ContextHocoy (1999) sought to apply Cross’s (1995) theory to a sample of South AfricansThe author chose South Africa because of the high salience of race, similar to the experience of African AmericansThe history of separation and discrimination based on race was shared as well (e.g. Plessey vs. Ferguson, Jim Crow Laws in the U.S., Apartheid in South Africa)

- 23. Cross’s Model in S. African Context:PreencounterHocoy found that the preencounter stage was present in the majority of the people that participated in the studyThe people in this sample who talked about being at this stage made statements such as “all that was White was good and beautiful . . . [and] all that was Black was bad and ugly,” and in which “Whites were superior.” (p.140)

- 24. Cross’s Model in S. African Context: EncounterStudents in the study talk about experiencing an incident that triggered an encounter stage in which they began to experience dissonance about themselves and their understanding of race. Hocoy states:One technikon student remembers a drastic shift in her worldview when she was confronted with a landlord who refused to rent the place to her because she was Black, despite being in a post apartheid South Africa. Another student remembers being beaten because a shop owner (wrongly) accused him of stealing, and another time in which he ran for his life as he was chased by attack dogs, which were sent by their White owners ‘to have a laugh’ at him. (pp.140-141)

- 25. Cross’s Model in S. African Context: Immersion/EmmersionAlmost all of the students in the study have said that they experienced a stage where they abandoned their Eurocentric worldview in favor of one that validates their identityThe people in his study described liberating themselves from “mental slavery (p.141)” and embracing their African heritage. This process was two-fold, as some people in the study also described having “fantasies of vengeance (p.141)” against White people

- 26. Cross’s Model in S. African Context: IntegrationSome participants described entering these stages, where they began to view White people as being no better or worse than Black peopleParticipants in the study made statements such as, "“only love can transform your enemy, [whereas] hate multiplies hate.” These participants demonstrated a more relaxed calm with regard to their identity; their Blackness had been internalized and they are now able to view life on other dimensions

- 27. Cross’s Model in S. African Context: Internalization/CommittementBlack South Africans that participated in this study, “displayed a continuing and lifelong commitment to the development of other Blacks” (p.142). One technikon counselor would spend her weekends in the townships providing workshops and counseling and in. This may be an indication that even for more acculturated South Africans that their communal nature of their heritage has survived.(p. 143)

- 28. Identity Development for CaribbeansSecond-generation Afro-Caribbeans had significantly higher internalization status attitudes than first-generation Afro-Caribbeans. Generational status and ethnic identity were not relatedEthnic identity does not block the development of racial identitySource:Hall, S. P., & Carter, R. T. (2006). The Relationship Between Racial Identity, Ethnic Identity, and Perceptions of Racial Discrimination in an Afro-Caribbean Descent Sample. Journal of Black Psychology, 32(2), 155-175.

- 29. Literature on cultural factorsPhelps, Taylor and Gerard (2001): Native African Americans has significantly higher levels of mistrust for other racial groups than immigrant African AmericansWaters (2001) and Kamya (1997): Immigrant African Americans have different ways of defining their ethnic identitySource: Kamya, H. A. (1997). African Immigrants in the United States: The Challenge for Research and Practice. Social Work, 42(2), 154-165.Phelps, R. E., Taylor, J. D., & Gerard, P. A. (2001). Cultural mistrust, ethnic identity, racial identity, and self-esteem among ethnically diverse Black university students. Journal of Counseling & Development, 79(2), 209-216.Waters, M. C. (2001). Black identities: West Indian immigrant dreams and American realities (1st Harvard University Press pbk. ed.). New York Cambridge, Mass.: Russell Sage Foundation ; Harvard University Press.

- 30. ReferencesBureau, U. S. C. Educational Attainment. from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/educ-attn.htmlChavous, T. M., Bernat, D. H., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Caldwell, C. H., Kohn-Wood, L., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2003). Racial Identity and Academic Attainment Among African American Adolescents. Child Development, 74(4), 1076-1090.Cross, W. E., Jr. (1995). The psychology of nigrescence: Revising the Cross model. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M.Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 93–122).Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Hall, S. P., & Carter, R. T. (2006). The Relationship Between Racial Identity, Ethnic Identity, and Perceptions of Racial Discrimination in an Afro-Caribbean Descent Sample. Journal of Black Psychology, 32(2), 155-175.Hocoy, D. (1999). The Validity of Cross's Model of Black Racial Identity Development in the South African Context. Journal of Black Psychology, 25(2), 131-151.Logan, J. R., & Deane, G. (2003). Black diversity in metropolitan America: Lewis Mumford Center, University at Albany, State University of New York.Garrod, A., Ward, J. V., Robinson, T. L., & Kilkenny, R. (Eds.). (1999). Souls looking back : life stories of growing up Black. New York: RoutledgeMassey, D. S., Mooney, M., Torress, K. C., & Charles, C. Z. (2007). Black Immigrants and Black Natives Attending Selective Colleges and Universities in the United States. American Journal of Education, 113.Rimer, S., & Arenson, K. W. (June 24th, 2004). Top Colleges Take More Blacks, But Which Ones? The New York Times.

![Cross’s Model in S. African Context:PreencounterHocoy found that the preencounter stage was present in the majority of the people that participated in the studyThe people in this sample who talked about being at this stage made statements such as “all that was White was good and beautiful . . . [and] all that was Black was bad and ugly,” and in which “Whites were superior.” (p.140)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/blackidentityducom-12632229117598-phpapp02/85/Variations-of-Black-Identity-23-320.jpg)

![Cross’s Model in S. African Context: IntegrationSome participants described entering these stages, where they began to view White people as being no better or worse than Black peopleParticipants in the study made statements such as, "“only love can transform your enemy, [whereas] hate multiplies hate.” These participants demonstrated a more relaxed calm with regard to their identity; their Blackness had been internalized and they are now able to view life on other dimensions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/blackidentityducom-12632229117598-phpapp02/85/Variations-of-Black-Identity-26-320.jpg)