1 of 15

Download to read offline

Recommended

Types of Arguments (1).pptx

Types of Arguments (1).pptxKlodjanaSkendaj

╠²

If there is something that would be considered difficult by most of the students but even young researchers, that would be to clearly define an argument and also manage to convey it without sounding judgemental or racist.Informal╠²FallaciesEnterline╠²Design╠²Services╠²LLCiStockThinkst.docx

Informal╠²FallaciesEnterline╠²Design╠²Services╠²LLCiStockThinkst.docxdirkrplav

╠²

Informal╠²Fallacies

Enterline╠²Design╠²Services╠²LLC/iStock/Thinkstock

Learning╠²Objectives

After╠²reading╠²this╠²chapter,╠²you╠²should╠²be╠²able╠²to:

1. Describe╠²the╠²various╠²fallacies╠²of╠²support,╠²their╠²origins,╠²and╠²circumstances╠²in╠²which╠²specific╠²arguments╠²may╠²not╠²be╠²fallacious.

2. Describe╠²the╠²various╠²fallacies╠²of╠²relevance,╠²their╠²origins,╠²and╠²circumstances╠²in╠²which╠²specific╠²arguments╠²may╠²not╠²be╠²fallacious.

3. Describe╠²the╠²various╠²fallacies╠²of╠²clarity,╠²their╠²origins,╠²and╠²circumstances╠²in╠²which╠²specific╠²arguments╠²may╠²not╠²be╠²fallacious.

We╠²can╠²conceive╠²of╠²logic╠²as╠²providing╠²us╠²with╠²the╠²best╠²tools╠²for╠²seeking╠²truth.╠²If╠²our╠²goal╠²is╠²to╠²seek╠²truth,╠²then╠²we╠²must╠²be╠²clear╠²that╠²the╠²task╠²isnot╠²limited╠²to╠²the╠²formation╠²of╠²true╠²beliefs╠²based╠²on╠²a╠²solid╠²logical╠²foundation,╠²for╠²the╠²task╠²also╠²involves╠²learning╠²to╠²avoid╠²forming╠²falsebeliefs.╠²Therefore,╠²just╠²as╠²it╠²is╠²important╠²to╠²learn╠²to╠²employ╠²good╠²reasoning,╠²it╠²is╠²also╠²important╠²to╠²learn╠²to╠²avoid╠²bad╠²reasoning.

Toward╠²this╠²end,╠²this╠²chapter╠²will╠²focus╠²on╠²fallacies.╠²Fallacies╠²are╠²errors╠²in╠²reasoning;╠²more╠²specifically,╠²they╠²are╠²common╠²patterns╠²ofreasoning╠²with╠²a╠²high╠²likelihood╠²of╠²leading╠²to╠²false╠²conclusions.╠²Logical╠²fallacies╠²often╠²seem╠²like╠²good╠²reasoning╠²because╠²they╠²resembleperfectly╠²legitimate╠²argument╠²forms.╠²For╠²example,╠²the╠²following╠²is╠²a╠²perfectly╠²valid╠²argument:

If╠²you╠²live╠²in╠²Paris,╠²then╠²you╠²live╠²in╠²France.

You╠²live╠²in╠²Paris.

Therefore,╠²you╠²live╠²in╠²France.

Assuming╠²that╠²both╠²of╠²the╠²premises╠²are╠²true,╠²it╠²logically╠²follows╠²that╠²the╠²conclusion╠²must╠²be╠²true.╠²The╠²following╠²argument╠²is╠²very╠²similar:

If╠²you╠²live╠²in╠²Paris,╠²then╠²you╠²live╠²in╠²France.

You╠²live╠²in╠²France.

Therefore,╠²you╠²live╠²in╠²Paris.

This╠²second╠²argument,╠²however,╠²is╠²invalid;╠²there╠²are╠²plenty╠²of╠²other╠²places╠²to╠²live╠²in╠²France.╠²This╠²is╠²a╠²common╠²formal╠²fallacy╠²known╠²asaffirming╠²the╠²consequent.╠²Chapter╠²4╠²discussed╠²how╠²this╠²fallacy╠²was╠²based╠²on╠²an╠²incorrect╠²logical╠²form.╠²This╠²chapter╠²will╠²focus╠²on╠²informalfallacies,╠²fallacies╠²whose╠²errors╠²are╠²not╠²so╠²much╠²a╠²matter╠²of╠²form╠²but╠²of╠²content.╠²The╠²rest╠²of╠²this╠²chapter╠²will╠²cover╠²some╠²of╠²the╠²most╠²commonand╠²important╠²fallacies,╠²with╠²definitions╠²and╠²examples.╠²Learning╠²about╠²fallacies╠²can╠²be╠²a╠²lot╠²of╠²fun,╠²but╠²be╠²warned:╠²Once╠²you╠²begin╠²noticingfallacies,╠²you╠²may╠²start╠²to╠²see╠²them╠²everywhere.

Before╠²we╠²start,╠²it╠²is╠²worth╠²noting╠²a╠²few╠²things.╠²First,╠²there╠²are╠²many,╠²many╠²fallacies.╠²This╠²chapter╠²will╠²consider╠²only╠²a╠²sampling╠²of╠²some╠²of╠²themost╠²well-known╠²fallacies.╠²Second,╠²there╠²is╠²a╠²lot╠²of╠²overlap╠²between╠²fallacies.╠²Reasonable╠²people╠²can╠²interpret╠²the╠²same╠²errors╠²as╠²differentfallacies.╠²Focus╠²on╠²trying╠²to╠²understand╠²both╠²interpretations╠²rather╠²than╠²on╠²insisting╠²that╠²only╠²one╠²can╠²be╠²right.╠²Third,╠²different╠²philosophersoften╠²have╠²different╠²terminology╠²for╠²the╠²same╠²fallacies╠²and╠²make╠²different╠²distinctions╠²among╠²them.╠²Therefore,╠²you╠²may╠²find╠²that╠²others╠²usedifferent╠²terminology╠²for╠²the╠²fallacies╠²that╠²we╠²will╠²learn╠²about╠²in╠²this╠²chapter.╠²Not╠²to╠²worryŌĆöit╠²is╠²the╠²ideas╠²here╠²that╠²are╠²most╠²important:╠²Ourgoal╠²is╠²to╠²learn╠²to╠²identi.Logic, fallacies, arguments and categorical statements.

Logic, fallacies, arguments and categorical statements.madandamoses1

╠²

This topic introduces you to logic, fallacies, categorical statements. The knowledge will enable you to analyze statements and make logical decisions.Chapter 9Practicing Effective CriticismThe principles of cha.docx

Chapter 9Practicing Effective CriticismThe principles of cha.docxchristinemaritza

╠²

Chapter 9

Practicing Effective Criticism

The principles of charity and accuracy govern the interpretation of argumentsŌĆöthey help you decide what the argument actually is. But once you have figured out what the argument is, you will want to evaluate it. In general, evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of arguments or other works is known as criticism. In everyday language, criticism is often assumed to be negativeŌĆöto criticize something is to say what is wrong with it. In the case of argumentation, however, criticism means to provide a more general analysis and evaluation of both the strengths and weaknesses of an argument. This section will focus on what constitutes good criticism and how you can criticize in a productive manner. Understanding how to properly critique an argument will also help you make your own arguments more effective.

When criticizing arguments, it is important to note both the strengths and weaknesses of an argument. Very few arguments are so bad that they have nothing at all to recommend them. Likewise, very few arguments are so perfect that they cannot be improved. Focusing only on an argumentŌĆÖs weaknesses or only on its strengths can make you seem biased. By noting both, you will not only be seen as less biased, you will also gain a better appreciation of the true state of the argument.

As we have seen, logical arguments are composed of premises and conclusions and the relation of inference between these. If an argument fails to establish its conclusion, then the problem might lie with one of the premises or with the inference drawn. So objections to arguments are mostly objections to premises or to inferences. A handy way of remembering this comes by way of the philosophical lore that all objections reduce to either ŌĆ£Oh yeah?ŌĆØ or ŌĆ£So what?ŌĆØ (Sturgeon, 1986).

Oh Yeah? Criticizing Premises

The ŌĆ£Oh yeah?ŌĆØ objection is made against a premise. A response of ŌĆ£Oh yeah?ŌĆØ means that the responder disagrees with what has been said, so it is an objection that a premise is either false or insufficiently supported.

Of course, if you are going to object to a premise, you really need to do more than just say, ŌĆ£Oh yeah?ŌĆØ At the very least, you should be prepared to say why you disagree with the premise. Whoever presented the argument has put the premise forward as true, and if all you can do is simply gainsay the person, then the discussion is not going to progress much. You need to support your objection with reasons for doubting the premise. The following is a list of questions that will help you not only methodically criticize arguments but also appreciate why your arguments receive negative criticism.

Is it central to the argument? The first thing to consider in questioning a premise is whether it is central to the argument. In other words, you should ask, ŌĆ£What would happen to the argument if the premise were wrong?ŌĆØ As noted in Chapter 5, inductive arguments can often remain fairly strong even if some of their premises turn ...Persuasive Writing

Persuasive Writingkarabeal

╠²

Persuasive writing aims to influence the audience's thoughts or actions by taking a stance for or against an issue. There are three main ways to persuade others: appealing to reason with evidence and logic, appealing to emotions with vivid examples and imagery, and appealing to one's character or credibility. When crafting a persuasive argument, it is important to address counterarguments, ensure evidence is from reliable sources, and anticipate objections in order to strengthen one's position.How to Make an Argument

How to Make an ArgumentLaura McKenzie

╠²

This lesson gives the basics of how to make an argument. It has lots of examples and fun pictures for students. It isBasic Attributes Of Questions

Basic Attributes Of Questionsrajendraamin

╠²

Effective survey questions have three key attributes: focus, brevity, and clarity. Questions should focus on a single, specific topic to get the most useful information. They should also be as brief as possible to avoid confusion and ensure respondents can easily understand and answer the question. Finally, the meaning of each question must be completely clear so all respondents interpret it the same way. Using precise, unambiguous wording and dichotomies can help achieve clarity.2397Informal FallaciesEnterline Design Services LLCiS.docx

2397Informal FallaciesEnterline Design Services LLCiS.docxvickeryr87

╠²

239

7Informal Fallacies

Enterline Design Services LLC/iStock/Thinkstock

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Describe the various fallacies of support, their origins, and circumstances in which specific

arguments may not be fallacious.

2. Describe the various fallacies of relevance, their origins, and circumstances in which

specific arguments may not be fallacious.

3. Describe the various fallacies of clarity, their origins, and circumstances in which specific

arguments may not be fallacious.

har85668_07_c07_239-278.indd 239 4/9/15 11:30 AM

┬® 2015 Bridgepoint Education, Inc. All rights reserved. Not for resale or redistribution.

We can conceive of logic as providing us with the best tools for seeking truth. If our goal is to

seek truth, then we must be clear that the task is not limited to the formation of true beliefs

based on a solid logical foundation, for the task also involves learning to avoid forming false

beliefs. Therefore, just as it is important to learn to employ good reasoning, it is also impor-

tant to learn to avoid bad reasoning.

Toward this end, this chapter will focus on fallacies. Fallacies are errors in reasoning; more

specifically, they are common patterns of reasoning with a high likelihood of leading to false

conclusions. Logical fallacies often seem like good reasoning because they resemble perfectly

legitimate argument forms. For example, the following is a perfectly valid argument:

If you live in Paris, then you live in France.

You live in Paris.

Therefore, you live in France.

Assuming that both of the premises are true, it logically follows that the conclusion must be

true. The following argument is very similar:

If you live in Paris, then you live in France.

You live in France.

Therefore, you live in Paris.

This second argument, however, is invalid; there are plenty of other places to live in France.

This is a common formal fallacy known as affirming the consequent. Chapter 4 discussed how

this fallacy was based on an incorrect logical form. This chapter will focus on informal falla-

cies, fallacies whose errors are not so much a matter of form but of content. The rest of this

chapter will cover some of the most common and important fallacies, with definitions and

examples. Learning about fallacies can be a lot of fun, but be warned: Once you begin noticing

fallacies, you may start to see them everywhere.

Before we start, it is worth noting a few things. First, there are many, many fallacies. This

chapter will consider only a sampling of some of the most well-known fallacies. Second, there

is a lot of overlap between fallacies. Reasonable people can interpret the same errors as dif-

ferent fallacies. Focus on trying to understand both interpretations rather than on insisting

that only one can be right. Third, different philosophers often have different terminology for

the same fallacies and make different distinctions among them. Theref.Human Person to the Philosophy-Q1-W2-3.pptx

Human Person to the Philosophy-Q1-W2-3.pptxpaulasolomon03

╠²

Lesson 2 in the Introduction to the Philosophy6a

6aHariz Mustafa

╠²

This document provides examples of logical fallacies discussed in Chapter 6 about fallacies of insufficient evidence. It analyzes arguments that commit the fallacies of appeal to ignorance and hasty generalization by failing to provide sufficient evidence to support their conclusions. Another argument uses a slippery slope fallacy in suggesting that watching cartoons will inevitably lead children to become toy-obsessed and out of control without proving the intermediate steps. The document demonstrates how to identify conclusions, analyze evidence used to support them, and determine if the reasoning commits a logical fallacy.The Point of the PaperYour paper is acritical evaluati.docx

The Point of the PaperYour paper is acritical evaluati.docxgabrielaj9

╠²

The Point of the Paper

Your paper is a

critical evaluation of the argument

that someone (you or someone else) gives in support of his or her position on this problem.

It is NOT a discussion of the conclusion, or of the second premise.

Common ProblemsReally a paper ŌĆ£pro-and-conŌĆØ the conclusionDid not evaluate the argumentOnly discussed premise two, reallyJustified Premise One, then abandoned itDid not try hard enough to understand what the theory is and how it worksJustifications that simply restate the argument in more wordsSAY WHAT YOU ARE WRITING ABOUT!!

For your introduction, describe and explain the problem that gives rise to the argument you are discussing. DO NOT explain the argument, summarize the argument, or repeat the argument.

Explain what the problem is that you are trying to solve

(or that the person whose argument you are discussing is trying to solve). Discuss why this particular subject is a problem, give a little history to set up the problem, etc. This section is usually two or three paragraphs.

Position ŌĆō one sentence!At the end of your introduction, it is natural to point out that there is a position that you (or someone else) takes on the problem. For example, if you are going to discuss your argument against the teaching of values in our schools, you would assert here that you are against it. On the other hand, if you are going to discuss William Bennett's argument in favor of such teaching, you would point out here that he is in favor of it. The point here is that your paper is about an argument that supports some position on the problem you have outlined in the introduction. State that position here. You should note two important things: the position stated here should be exactly the conclusion of the argument in the next section, and this is not the place to express your opinion. You may, in fact, disagree with the position defended by the argument that your paper is about, and it is fine to point that out here, but do so in one sentence only. For example, you might say: "Bennett's position on this subject is that values should be taught in schools. I am, however, opposed." This part of the paper is normally one or two sentences long.

ARGUMENTImmediately following the position statement you should present the argument that supports the position (either yours or someone else's). It should be presented with numbered premises and a conclusion that is also numbered. There should be a horizontal line separating the premises from the conclusion. For example:(1) If the teaching of values in schools will revive America's flagging morality, then values should be taught in schools.(2) The teaching of values in schools will revive America's flagging morality.(3) Therefore values should be taught in schools.

NOTE: THE CONCLUSION IS THE POSITION!!

Justification I ŌĆō 1 of Top 3 partsFirst, you should defend the validity of your argument. If your argument is an immediately recognizable form, you may say si.Persuasive speech

Persuasive speechlaineyindia

╠²

This document provides guidance on how to write a persuasive speech or argument. It discusses identifying a topic and position, including 3 reasons to support the argument, and writing a conclusion. It also provides examples of persuasive techniques to use, such as asking questions, using facts and statistics, and repetition. Sample persuasive words and phrases are given to use in a speech, along with guidance on how to structure the introduction, body, and conclusion of a persuasive argument.Extra credit speech

Extra credit speechburkeeny

╠²

The document discusses critical thinking and how to evaluate claims. It explains that critical thinkers rely on evidence rather than general truths to make their arguments. A continuum of certainty measures the validity of claims from 0% to 100% validity. When assessing a claim, one should determine if the data provided sufficiently supports the claim, understand how the data relates to the claim, consider other perspectives, and ask questions before accepting a position. The document provides an exercise asking readers to think through scenarios to test their critical thinking abilities.PowerPoint Textbook. Validity and Truth-2-1-1.pptx

PowerPoint Textbook. Validity and Truth-2-1-1.pptxUsamaHassan88

╠²

This document discusses evaluating the validity of arguments. It explains that for an argument to be valid, the premises must logically support and prove the conclusion. If the premises are true, they should make the conclusion true as well. Invalid arguments have conclusions that are not logically supported by the premises. The document uses examples to illustrate valid and invalid arguments. It emphasizes that validity assesses an argument's structure and logical connection between premises and conclusion, not whether the premises are factually true.Chapter 3

Chapter 3scrasnow

╠²

The document discusses different types of arguments and how to evaluate them. It defines deductive and inductive arguments. Deductive arguments aim to provide conclusive support for a conclusion, while inductive arguments provide probable but not conclusive support. An argument is valid if the conclusion must be true if the premises are true, and sound if it is also valid and has true premises. An inductive argument is strong if the premises make the conclusion highly probable, and cogent if it is also strong and has true premises. The document outlines four steps to judge arguments and discusses common argument patterns like modus ponens, modus tollens, and disjunctive syllogism.Poor Reasoning and Fallacies Cheat Sheet Appeal to the Pe.docx

Poor Reasoning and Fallacies Cheat Sheet Appeal to the Pe.docxharrisonhoward80223

╠²

Poor Reasoning and Fallacies Cheat Sheet

Appeal to the People (Bandwagon) - Claiming that something is true just because many people

believe it is. Example: Everybody buys this product, so it must be the best one.

Faulty Appeal to Authority - Using research without naming the source, such as, "Many researchers

say..." or answering questions one is not qualified to answer. Example: I asked my dentist if he thought

this mole was cancerous. He said ŌĆ£NoŌĆØ so I do not need to get it checked out.

Proof by Lack of Evidence (Burden of Proof) - Asserting something is true just because there is no

evidence it's false. Example: UFOŌĆÖs exist because no one has ever been able to prove they donŌĆÖt.

Innuendo ŌĆō Making a claim without actually making the claim. Example:

Non Sequitur - It doesn't follow logically. Samantha lives in a large building; therefore she must have a

large home.

Fake Dilemma (Black and White) ŌĆō Presenting two alternative states as the only possibilities, when in

fact there are more. Example: "You are either for the U.S. or against the U.S." doesn't allow for neutral

countries.

Naturalistic Fallacy (Appeal to Nature) - Making the argument because something is ŌĆ£naturalŌĆØ, it is

therefore valid, good or the way itŌĆÖs supposed to be. Example: This product uses all natural ingredients

therefore itŌĆÖs the only one on the market you should buy.

Circular Reasoning (Begging the Question) ŌĆō Using the statement to prove the conclusion and the

conclusion to prove the statement. Example: The word of Zorbo the Great is flawless and perfect. We know this

because it says so in The Great and Infallible Book of Zorbo's Best and Most Truest Things that are Definitely True and

Should Not Ever Be Questioned.

Overgeneralization ŌĆō Asserting something is an entire class of things when it may not be true for all

members of the class. Example: Beth is a Psychology student and shy is shy, therefore all psychology

students are shy.

False Analogy (Slippery Slope) ŌĆō Making a false or misleading analogy. Example: Colin Closet asserts

that if we allow same-sex couples to marry, then the next thing we know we'll be allowing people to marry their

parents, their cars and even monkeys.

Jumping to Conclusions ŌĆō Drawing conclusions with little evidence. Example: My son is crying, you

must have taken his toy.

Being Unrealistic ŌĆō Using only information in an unrealistic manner. Example: The candidates just all

graduated from collegeŌĆ” therefore they should not take a job for less than 6 figures.

Verbal Fallacies (Ambiguity) ŌĆō Accenting, omitting, or misusing certain words to influence or mislead

the reader or listener. Example: After the team lost, Susan became mad. (upset, angry, insane, happyŌĆ”

who knows)

Using only information that supports your argument (Texas Sharpshooter) - Example: Research

says a glass of wine a day is good for my heart. So drinking is good for my heart!

Source: Jesse Ri.Validity

Validitydyeakel

╠²

1) An argument is valid if its premises guarantee the truth of its conclusion, while a strong argument makes the conclusion likely if the premises are true.

2) An argument is valid if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

3) Validity depends only on the logical form of the argument, not the truth of the premises. Valid arguments can have false premises and conclusions.EAPP Position Paper Powerpoint Presentation

EAPP Position Paper Powerpoint Presentationevafecampanado1

╠²

This document provides guidance on developing logical arguments supported by evidence. It begins by explaining the importance of justifying positions with logic rather than personal opinions alone. The objectives are then outlined as defending a position with reasonable arguments and cited evidence, identifying logical fallacies, and evaluating the authenticity of sources. Key terms are defined, including "stand", "claims", "evidence", and "fallacies". Common logical fallacies are explained such as false dilemma, appeal to ignorance, and slippery slope. Criteria for evaluating source authenticity and validity are presented, including relevance, authority of the author, date of publication, accuracy of information, and source location. The document advises avoiding logical fallacies and carefully evaluating sources used toSkimming and scanning

Skimming and scanningEnglish Online Inc.

╠²

Skimming and scanning are reading techniques used to read something fast. Skimming involves reading quickly to get the general idea, while scanning means reading quickly to find specific facts. Examples of when to skim include news articles and websites, while examples of when to scan include schedules and receipts. When skimming, readers should read the title, topic sentences, subtitles, and last paragraph. Transition words are used to connect ideas and show relationships between sentences like cause and effect, contrast, similarity, and time or place. Practicing identifying the correct transition for a given context can improve reading comprehension.Categorical syllogism

Categorical syllogismNoel Jopson

╠²

The document discusses categorical syllogisms and logical fallacies. It defines a categorical syllogism as having two premises and one conclusion, where each proposition is in one of four forms: A, E, I, or O. It explains the terms, premises, and rules of syllogisms. It then discusses formal fallacies as errors of logical form and informal fallacies as errors of language. Examples are provided of fallacies of ambiguity, relevance, and presumption.EOI - C2 Science and technology - 23.pdf

EOI - C2 Science and technology - 23.pdfPaulina611888

╠²

This monologue discusses current and potential future applications of artificial intelligence, threats and risks related to AI, and its impact on the job market. It expresses optimism about AI's potential while acknowledging challenges regarding its regulation. The monologue concludes that with proper oversight, AI can greatly benefit humanity.4 Mistakes in Reasoning The World of Fallaciesboy at chalkboar.docx

4 Mistakes in Reasoning The World of Fallaciesboy at chalkboar.docxgilbertkpeters11344

╠²

4 Mistakes in Reasoning: The World of Fallacies

boy at chalkboard, puzzled at two math equations, 2+2=4 and 3+3=7

Have you ever heard of Plato, Aristotle, Socrates? Morons!

ŌĆöVizzini, The Princess Bride

So far we have looked at how to construct arguments and how to evaluate them. We've seen that arguments are constructed from sentences, with some sentences providing reasons, or premises, for another sentence, the conclusion. The purpose of arguments is to provide support for a conclusion. In a valid deductive argument, we must accept the conclusion as true if we accept the premises as true. A sound deductive argument is valid, and the premises are taken to be true. Inductive arguments, in contrast, are evaluated on a continuous scale from very strong to very weak: the stronger the inductive argument, the more likely the conclusion, given the premises.

What We Will Be Exploring

We will look at mistakes in reasoning, known as fallacies.

We will examine how these kinds of mistakes occur.

We will see that errors in reasoning can take place because of the structure of the argument.

We will discover that different errors in reasoning arise due to using language illegitimately, requiring close attention be paid to that language.

Generally, we want our arguments to be "good" argumentsŌĆösound deductive arguments and strong inductive arguments. Unfortunately, arguments often look good when they are not. Such arguments are said to commit a fallacy, a mistake in reasoning. Wide ranges of fallacies have been identified, but we will look at only some of the most common ones. When trying to construct a good argument, it is important to be able to identify what bad arguments look like. Then we can avoid making these mistakes ourselves and prevent others from trying to convince us of something on the basis of bad reasoning!

4.1

What Is a Fallacy?

image

The French village of Roussillon at sunrise. Roussillon is in Vaucluse, Provence. It would be a fallacy to assume that because someone lives in France, he or she lives in Paris.

Most simply, a fallacy is an error in reasoning. It is different from simply being mistaken, however. For instance, if someone were to say that "2 + 3 = 6," that would be a mistake, but it would not be a fallacy. Fallacies involve inferences, the move from one sentence (or a set of sentences) to another. Here's an example:

If I live in Paris, then I live in France.

I live in France.

Therefore,

I live in Paris.

Here, we have two premises and a conclusion. The first sentence is a conditional, and we can accept it as true. Let's assume the second sentence is also true. But even if those two premises were true, the conclusion would not be true. While it may be true that if I live in Paris then I live in France, and it may be true that I live in France, it does not follow that I live in Paris, because I could live in any number of other places in France. Thus, the inference from the .1Paper #1 Topic (Capital Punishment)Argument┬Ę If A Then B.docx

1Paper #1 Topic (Capital Punishment)Argument┬Ę If A Then B.docxRAJU852744

╠²

1

Paper #1 Topic (Capital Punishment)Argument

┬Ę If A Then B

┬Ę If capital punishment is an appropriate expression of the anger society feels about horrible crimes, and it is simply what such criminals deserve then, capital punishment is morally right.

┬Ę A

┬Ę capital punishment is an appropriate expression of the anger society feels about horrible crimes, and it is simply what such criminals deserve.

┬Ę Therefore, B

┬Ę Therefore, capital punishment is morally right.

The Point of the Paper

Your paper is a

critical evaluation of the argument

that someone (you or someone else) gives in support of his or her position on this problem.

It is NOT a discussion of the conclusion, or of the second premise.

Common ProblemsReally a paper ŌĆ£pro-and-conŌĆØ the conclusionDid not evaluate the argumentOnly discussed premise two, reallyJustified Premise One, then abandoned itDid not try hard enough to understand what the theory is and how it worksJustifications that simply restate the argument in more wordsSAY WHAT YOU ARE WRITING ABOUT!!

For your introduction, describe and explain the problem that gives rise to the argument you are discussing. DO NOT explain the argument, summarize the argument, or repeat the argument.

Explain what the problem is that you are trying to solve

(or that the person whose argument you are discussing is trying to solve). Discuss why this particular subject is a problem, give a little history to set up the problem, etc. This section is usually two or three paragraphs.

Position ŌĆō one sentence!At the end of your introduction, it is natural to point out that there is a position that you (or someone else) takes on the problem. For example, if you are going to discuss your argument against the teaching of values in our schools, you would assert here that you are against it. On the other hand, if you are going to discuss William Bennett's argument in favor of such teaching, you would point out here that he is in favor of it. The point here is that your paper is about an argument that supports some position on the problem you have outlined in the introduction. State that position here. You should note two important things: the position stated here should be exactly the conclusion of the argument in the next section, and this is not the place to express your opinion. You may, in fact, disagree with the position defended by the argument that your paper is about, and it is fine to point that out here, but do so in one sentence only. For example, you might say: "Bennett's position on this subject is that values should be taught in schools. I am, however, opposed." This part of the paper is normally one or two sentences long.

ARGUMENTImmediately following the position statement you should present the argument that supports the position (either yours or someone else's). It should be presented with numbered premises and a conclusion that is also numbered. There should be a horizontal line separating the premises from the con.Best Woodworking Classes Near Me Today..

Best Woodworking Classes Near Me Today..John A. Elewa

╠²

Welcome to our comprehensive guide on getting started with woodworking in 2025. Whether you're a complete novice or looking to refine your skills, this presentation will provide valuable insights into the world of woodworking.

Woodworking is a rewarding craft that combines creativity, skill, and practicality. For beginners wondering how to start woodworking, we'll cover essential steps like acquiring basic tools, setting up a workspace, and choosing your first projects. We'll explore easy woodworking projects that are perfect for building confidence and developing fundamental techniques.

For those seeking structured learning, we'll discuss the benefits of woodworking classes near you, including options from popular providers like Rockler Woodworking. These classes offer hands-on experience and expert guidance to accelerate your learning.

We'll also delve into the must-have woodworking tools for beginners and how to use them safely and effectively. As you progress, we'll introduce more advanced woodworking projects to challenge and expand your skills.

Finally, for those interested in turning their hobby into a side hustle, we'll highlight woodworking projects that sell well in today's market.More Related Content

Similar to Deductive-and-Inductive-Argument.. logic (20)

Persuasive Writing

Persuasive Writingkarabeal

╠²

Persuasive writing aims to influence the audience's thoughts or actions by taking a stance for or against an issue. There are three main ways to persuade others: appealing to reason with evidence and logic, appealing to emotions with vivid examples and imagery, and appealing to one's character or credibility. When crafting a persuasive argument, it is important to address counterarguments, ensure evidence is from reliable sources, and anticipate objections in order to strengthen one's position.How to Make an Argument

How to Make an ArgumentLaura McKenzie

╠²

This lesson gives the basics of how to make an argument. It has lots of examples and fun pictures for students. It isBasic Attributes Of Questions

Basic Attributes Of Questionsrajendraamin

╠²

Effective survey questions have three key attributes: focus, brevity, and clarity. Questions should focus on a single, specific topic to get the most useful information. They should also be as brief as possible to avoid confusion and ensure respondents can easily understand and answer the question. Finally, the meaning of each question must be completely clear so all respondents interpret it the same way. Using precise, unambiguous wording and dichotomies can help achieve clarity.2397Informal FallaciesEnterline Design Services LLCiS.docx

2397Informal FallaciesEnterline Design Services LLCiS.docxvickeryr87

╠²

239

7Informal Fallacies

Enterline Design Services LLC/iStock/Thinkstock

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Describe the various fallacies of support, their origins, and circumstances in which specific

arguments may not be fallacious.

2. Describe the various fallacies of relevance, their origins, and circumstances in which

specific arguments may not be fallacious.

3. Describe the various fallacies of clarity, their origins, and circumstances in which specific

arguments may not be fallacious.

har85668_07_c07_239-278.indd 239 4/9/15 11:30 AM

┬® 2015 Bridgepoint Education, Inc. All rights reserved. Not for resale or redistribution.

We can conceive of logic as providing us with the best tools for seeking truth. If our goal is to

seek truth, then we must be clear that the task is not limited to the formation of true beliefs

based on a solid logical foundation, for the task also involves learning to avoid forming false

beliefs. Therefore, just as it is important to learn to employ good reasoning, it is also impor-

tant to learn to avoid bad reasoning.

Toward this end, this chapter will focus on fallacies. Fallacies are errors in reasoning; more

specifically, they are common patterns of reasoning with a high likelihood of leading to false

conclusions. Logical fallacies often seem like good reasoning because they resemble perfectly

legitimate argument forms. For example, the following is a perfectly valid argument:

If you live in Paris, then you live in France.

You live in Paris.

Therefore, you live in France.

Assuming that both of the premises are true, it logically follows that the conclusion must be

true. The following argument is very similar:

If you live in Paris, then you live in France.

You live in France.

Therefore, you live in Paris.

This second argument, however, is invalid; there are plenty of other places to live in France.

This is a common formal fallacy known as affirming the consequent. Chapter 4 discussed how

this fallacy was based on an incorrect logical form. This chapter will focus on informal falla-

cies, fallacies whose errors are not so much a matter of form but of content. The rest of this

chapter will cover some of the most common and important fallacies, with definitions and

examples. Learning about fallacies can be a lot of fun, but be warned: Once you begin noticing

fallacies, you may start to see them everywhere.

Before we start, it is worth noting a few things. First, there are many, many fallacies. This

chapter will consider only a sampling of some of the most well-known fallacies. Second, there

is a lot of overlap between fallacies. Reasonable people can interpret the same errors as dif-

ferent fallacies. Focus on trying to understand both interpretations rather than on insisting

that only one can be right. Third, different philosophers often have different terminology for

the same fallacies and make different distinctions among them. Theref.Human Person to the Philosophy-Q1-W2-3.pptx

Human Person to the Philosophy-Q1-W2-3.pptxpaulasolomon03

╠²

Lesson 2 in the Introduction to the Philosophy6a

6aHariz Mustafa

╠²

This document provides examples of logical fallacies discussed in Chapter 6 about fallacies of insufficient evidence. It analyzes arguments that commit the fallacies of appeal to ignorance and hasty generalization by failing to provide sufficient evidence to support their conclusions. Another argument uses a slippery slope fallacy in suggesting that watching cartoons will inevitably lead children to become toy-obsessed and out of control without proving the intermediate steps. The document demonstrates how to identify conclusions, analyze evidence used to support them, and determine if the reasoning commits a logical fallacy.The Point of the PaperYour paper is acritical evaluati.docx

The Point of the PaperYour paper is acritical evaluati.docxgabrielaj9

╠²

The Point of the Paper

Your paper is a

critical evaluation of the argument

that someone (you or someone else) gives in support of his or her position on this problem.

It is NOT a discussion of the conclusion, or of the second premise.

Common ProblemsReally a paper ŌĆ£pro-and-conŌĆØ the conclusionDid not evaluate the argumentOnly discussed premise two, reallyJustified Premise One, then abandoned itDid not try hard enough to understand what the theory is and how it worksJustifications that simply restate the argument in more wordsSAY WHAT YOU ARE WRITING ABOUT!!

For your introduction, describe and explain the problem that gives rise to the argument you are discussing. DO NOT explain the argument, summarize the argument, or repeat the argument.

Explain what the problem is that you are trying to solve

(or that the person whose argument you are discussing is trying to solve). Discuss why this particular subject is a problem, give a little history to set up the problem, etc. This section is usually two or three paragraphs.

Position ŌĆō one sentence!At the end of your introduction, it is natural to point out that there is a position that you (or someone else) takes on the problem. For example, if you are going to discuss your argument against the teaching of values in our schools, you would assert here that you are against it. On the other hand, if you are going to discuss William Bennett's argument in favor of such teaching, you would point out here that he is in favor of it. The point here is that your paper is about an argument that supports some position on the problem you have outlined in the introduction. State that position here. You should note two important things: the position stated here should be exactly the conclusion of the argument in the next section, and this is not the place to express your opinion. You may, in fact, disagree with the position defended by the argument that your paper is about, and it is fine to point that out here, but do so in one sentence only. For example, you might say: "Bennett's position on this subject is that values should be taught in schools. I am, however, opposed." This part of the paper is normally one or two sentences long.

ARGUMENTImmediately following the position statement you should present the argument that supports the position (either yours or someone else's). It should be presented with numbered premises and a conclusion that is also numbered. There should be a horizontal line separating the premises from the conclusion. For example:(1) If the teaching of values in schools will revive America's flagging morality, then values should be taught in schools.(2) The teaching of values in schools will revive America's flagging morality.(3) Therefore values should be taught in schools.

NOTE: THE CONCLUSION IS THE POSITION!!

Justification I ŌĆō 1 of Top 3 partsFirst, you should defend the validity of your argument. If your argument is an immediately recognizable form, you may say si.Persuasive speech

Persuasive speechlaineyindia

╠²

This document provides guidance on how to write a persuasive speech or argument. It discusses identifying a topic and position, including 3 reasons to support the argument, and writing a conclusion. It also provides examples of persuasive techniques to use, such as asking questions, using facts and statistics, and repetition. Sample persuasive words and phrases are given to use in a speech, along with guidance on how to structure the introduction, body, and conclusion of a persuasive argument.Extra credit speech

Extra credit speechburkeeny

╠²

The document discusses critical thinking and how to evaluate claims. It explains that critical thinkers rely on evidence rather than general truths to make their arguments. A continuum of certainty measures the validity of claims from 0% to 100% validity. When assessing a claim, one should determine if the data provided sufficiently supports the claim, understand how the data relates to the claim, consider other perspectives, and ask questions before accepting a position. The document provides an exercise asking readers to think through scenarios to test their critical thinking abilities.PowerPoint Textbook. Validity and Truth-2-1-1.pptx

PowerPoint Textbook. Validity and Truth-2-1-1.pptxUsamaHassan88

╠²

This document discusses evaluating the validity of arguments. It explains that for an argument to be valid, the premises must logically support and prove the conclusion. If the premises are true, they should make the conclusion true as well. Invalid arguments have conclusions that are not logically supported by the premises. The document uses examples to illustrate valid and invalid arguments. It emphasizes that validity assesses an argument's structure and logical connection between premises and conclusion, not whether the premises are factually true.Chapter 3

Chapter 3scrasnow

╠²

The document discusses different types of arguments and how to evaluate them. It defines deductive and inductive arguments. Deductive arguments aim to provide conclusive support for a conclusion, while inductive arguments provide probable but not conclusive support. An argument is valid if the conclusion must be true if the premises are true, and sound if it is also valid and has true premises. An inductive argument is strong if the premises make the conclusion highly probable, and cogent if it is also strong and has true premises. The document outlines four steps to judge arguments and discusses common argument patterns like modus ponens, modus tollens, and disjunctive syllogism.Poor Reasoning and Fallacies Cheat Sheet Appeal to the Pe.docx

Poor Reasoning and Fallacies Cheat Sheet Appeal to the Pe.docxharrisonhoward80223

╠²

Poor Reasoning and Fallacies Cheat Sheet

Appeal to the People (Bandwagon) - Claiming that something is true just because many people

believe it is. Example: Everybody buys this product, so it must be the best one.

Faulty Appeal to Authority - Using research without naming the source, such as, "Many researchers

say..." or answering questions one is not qualified to answer. Example: I asked my dentist if he thought

this mole was cancerous. He said ŌĆ£NoŌĆØ so I do not need to get it checked out.

Proof by Lack of Evidence (Burden of Proof) - Asserting something is true just because there is no

evidence it's false. Example: UFOŌĆÖs exist because no one has ever been able to prove they donŌĆÖt.

Innuendo ŌĆō Making a claim without actually making the claim. Example:

Non Sequitur - It doesn't follow logically. Samantha lives in a large building; therefore she must have a

large home.

Fake Dilemma (Black and White) ŌĆō Presenting two alternative states as the only possibilities, when in

fact there are more. Example: "You are either for the U.S. or against the U.S." doesn't allow for neutral

countries.

Naturalistic Fallacy (Appeal to Nature) - Making the argument because something is ŌĆ£naturalŌĆØ, it is

therefore valid, good or the way itŌĆÖs supposed to be. Example: This product uses all natural ingredients

therefore itŌĆÖs the only one on the market you should buy.

Circular Reasoning (Begging the Question) ŌĆō Using the statement to prove the conclusion and the

conclusion to prove the statement. Example: The word of Zorbo the Great is flawless and perfect. We know this

because it says so in The Great and Infallible Book of Zorbo's Best and Most Truest Things that are Definitely True and

Should Not Ever Be Questioned.

Overgeneralization ŌĆō Asserting something is an entire class of things when it may not be true for all

members of the class. Example: Beth is a Psychology student and shy is shy, therefore all psychology

students are shy.

False Analogy (Slippery Slope) ŌĆō Making a false or misleading analogy. Example: Colin Closet asserts

that if we allow same-sex couples to marry, then the next thing we know we'll be allowing people to marry their

parents, their cars and even monkeys.

Jumping to Conclusions ŌĆō Drawing conclusions with little evidence. Example: My son is crying, you

must have taken his toy.

Being Unrealistic ŌĆō Using only information in an unrealistic manner. Example: The candidates just all

graduated from collegeŌĆ” therefore they should not take a job for less than 6 figures.

Verbal Fallacies (Ambiguity) ŌĆō Accenting, omitting, or misusing certain words to influence or mislead

the reader or listener. Example: After the team lost, Susan became mad. (upset, angry, insane, happyŌĆ”

who knows)

Using only information that supports your argument (Texas Sharpshooter) - Example: Research

says a glass of wine a day is good for my heart. So drinking is good for my heart!

Source: Jesse Ri.Validity

Validitydyeakel

╠²

1) An argument is valid if its premises guarantee the truth of its conclusion, while a strong argument makes the conclusion likely if the premises are true.

2) An argument is valid if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

3) Validity depends only on the logical form of the argument, not the truth of the premises. Valid arguments can have false premises and conclusions.EAPP Position Paper Powerpoint Presentation

EAPP Position Paper Powerpoint Presentationevafecampanado1

╠²

This document provides guidance on developing logical arguments supported by evidence. It begins by explaining the importance of justifying positions with logic rather than personal opinions alone. The objectives are then outlined as defending a position with reasonable arguments and cited evidence, identifying logical fallacies, and evaluating the authenticity of sources. Key terms are defined, including "stand", "claims", "evidence", and "fallacies". Common logical fallacies are explained such as false dilemma, appeal to ignorance, and slippery slope. Criteria for evaluating source authenticity and validity are presented, including relevance, authority of the author, date of publication, accuracy of information, and source location. The document advises avoiding logical fallacies and carefully evaluating sources used toSkimming and scanning

Skimming and scanningEnglish Online Inc.

╠²

Skimming and scanning are reading techniques used to read something fast. Skimming involves reading quickly to get the general idea, while scanning means reading quickly to find specific facts. Examples of when to skim include news articles and websites, while examples of when to scan include schedules and receipts. When skimming, readers should read the title, topic sentences, subtitles, and last paragraph. Transition words are used to connect ideas and show relationships between sentences like cause and effect, contrast, similarity, and time or place. Practicing identifying the correct transition for a given context can improve reading comprehension.Categorical syllogism

Categorical syllogismNoel Jopson

╠²

The document discusses categorical syllogisms and logical fallacies. It defines a categorical syllogism as having two premises and one conclusion, where each proposition is in one of four forms: A, E, I, or O. It explains the terms, premises, and rules of syllogisms. It then discusses formal fallacies as errors of logical form and informal fallacies as errors of language. Examples are provided of fallacies of ambiguity, relevance, and presumption.EOI - C2 Science and technology - 23.pdf

EOI - C2 Science and technology - 23.pdfPaulina611888

╠²

This monologue discusses current and potential future applications of artificial intelligence, threats and risks related to AI, and its impact on the job market. It expresses optimism about AI's potential while acknowledging challenges regarding its regulation. The monologue concludes that with proper oversight, AI can greatly benefit humanity.4 Mistakes in Reasoning The World of Fallaciesboy at chalkboar.docx

4 Mistakes in Reasoning The World of Fallaciesboy at chalkboar.docxgilbertkpeters11344

╠²

4 Mistakes in Reasoning: The World of Fallacies

boy at chalkboard, puzzled at two math equations, 2+2=4 and 3+3=7

Have you ever heard of Plato, Aristotle, Socrates? Morons!

ŌĆöVizzini, The Princess Bride

So far we have looked at how to construct arguments and how to evaluate them. We've seen that arguments are constructed from sentences, with some sentences providing reasons, or premises, for another sentence, the conclusion. The purpose of arguments is to provide support for a conclusion. In a valid deductive argument, we must accept the conclusion as true if we accept the premises as true. A sound deductive argument is valid, and the premises are taken to be true. Inductive arguments, in contrast, are evaluated on a continuous scale from very strong to very weak: the stronger the inductive argument, the more likely the conclusion, given the premises.

What We Will Be Exploring

We will look at mistakes in reasoning, known as fallacies.

We will examine how these kinds of mistakes occur.

We will see that errors in reasoning can take place because of the structure of the argument.

We will discover that different errors in reasoning arise due to using language illegitimately, requiring close attention be paid to that language.

Generally, we want our arguments to be "good" argumentsŌĆösound deductive arguments and strong inductive arguments. Unfortunately, arguments often look good when they are not. Such arguments are said to commit a fallacy, a mistake in reasoning. Wide ranges of fallacies have been identified, but we will look at only some of the most common ones. When trying to construct a good argument, it is important to be able to identify what bad arguments look like. Then we can avoid making these mistakes ourselves and prevent others from trying to convince us of something on the basis of bad reasoning!

4.1

What Is a Fallacy?

image

The French village of Roussillon at sunrise. Roussillon is in Vaucluse, Provence. It would be a fallacy to assume that because someone lives in France, he or she lives in Paris.

Most simply, a fallacy is an error in reasoning. It is different from simply being mistaken, however. For instance, if someone were to say that "2 + 3 = 6," that would be a mistake, but it would not be a fallacy. Fallacies involve inferences, the move from one sentence (or a set of sentences) to another. Here's an example:

If I live in Paris, then I live in France.

I live in France.

Therefore,

I live in Paris.

Here, we have two premises and a conclusion. The first sentence is a conditional, and we can accept it as true. Let's assume the second sentence is also true. But even if those two premises were true, the conclusion would not be true. While it may be true that if I live in Paris then I live in France, and it may be true that I live in France, it does not follow that I live in Paris, because I could live in any number of other places in France. Thus, the inference from the .1Paper #1 Topic (Capital Punishment)Argument┬Ę If A Then B.docx

1Paper #1 Topic (Capital Punishment)Argument┬Ę If A Then B.docxRAJU852744

╠²

1

Paper #1 Topic (Capital Punishment)Argument

┬Ę If A Then B

┬Ę If capital punishment is an appropriate expression of the anger society feels about horrible crimes, and it is simply what such criminals deserve then, capital punishment is morally right.

┬Ę A

┬Ę capital punishment is an appropriate expression of the anger society feels about horrible crimes, and it is simply what such criminals deserve.

┬Ę Therefore, B

┬Ę Therefore, capital punishment is morally right.

The Point of the Paper

Your paper is a

critical evaluation of the argument

that someone (you or someone else) gives in support of his or her position on this problem.

It is NOT a discussion of the conclusion, or of the second premise.

Common ProblemsReally a paper ŌĆ£pro-and-conŌĆØ the conclusionDid not evaluate the argumentOnly discussed premise two, reallyJustified Premise One, then abandoned itDid not try hard enough to understand what the theory is and how it worksJustifications that simply restate the argument in more wordsSAY WHAT YOU ARE WRITING ABOUT!!

For your introduction, describe and explain the problem that gives rise to the argument you are discussing. DO NOT explain the argument, summarize the argument, or repeat the argument.

Explain what the problem is that you are trying to solve

(or that the person whose argument you are discussing is trying to solve). Discuss why this particular subject is a problem, give a little history to set up the problem, etc. This section is usually two or three paragraphs.

Position ŌĆō one sentence!At the end of your introduction, it is natural to point out that there is a position that you (or someone else) takes on the problem. For example, if you are going to discuss your argument against the teaching of values in our schools, you would assert here that you are against it. On the other hand, if you are going to discuss William Bennett's argument in favor of such teaching, you would point out here that he is in favor of it. The point here is that your paper is about an argument that supports some position on the problem you have outlined in the introduction. State that position here. You should note two important things: the position stated here should be exactly the conclusion of the argument in the next section, and this is not the place to express your opinion. You may, in fact, disagree with the position defended by the argument that your paper is about, and it is fine to point that out here, but do so in one sentence only. For example, you might say: "Bennett's position on this subject is that values should be taught in schools. I am, however, opposed." This part of the paper is normally one or two sentences long.

ARGUMENTImmediately following the position statement you should present the argument that supports the position (either yours or someone else's). It should be presented with numbered premises and a conclusion that is also numbered. There should be a horizontal line separating the premises from the con.Recently uploaded (13)

Best Woodworking Classes Near Me Today..

Best Woodworking Classes Near Me Today..John A. Elewa

╠²

Welcome to our comprehensive guide on getting started with woodworking in 2025. Whether you're a complete novice or looking to refine your skills, this presentation will provide valuable insights into the world of woodworking.

Woodworking is a rewarding craft that combines creativity, skill, and practicality. For beginners wondering how to start woodworking, we'll cover essential steps like acquiring basic tools, setting up a workspace, and choosing your first projects. We'll explore easy woodworking projects that are perfect for building confidence and developing fundamental techniques.

For those seeking structured learning, we'll discuss the benefits of woodworking classes near you, including options from popular providers like Rockler Woodworking. These classes offer hands-on experience and expert guidance to accelerate your learning.

We'll also delve into the must-have woodworking tools for beginners and how to use them safely and effectively. As you progress, we'll introduce more advanced woodworking projects to challenge and expand your skills.

Finally, for those interested in turning their hobby into a side hustle, we'll highlight woodworking projects that sell well in today's market.L 6 Method to Fulfill Basic Human Aspirations v2.ppt

L 6 Method to Fulfill Basic Human Aspirations v2.pptAkashV75

╠²

Methods to fulfill basic human aspirationsDEVELOPING AN AUTHENTIC PERFORMANCE TASK.pptx

DEVELOPING AN AUTHENTIC PERFORMANCE TASK.pptxwaqasulbari560

╠²

Managing stress is essential for overall well-being. Effective coping strategies include deep breathing, exercise, meditation, healthy eating, and sufficient sleep. Engaging in hobbies, socializing, and maintaining a positive mindset also help. Time management and setting realistic goals reduce stress.Getting Things Done:ŌĆ©ŌĆ©personal productivity management ŌĆ©from the perspective ...

Getting Things Done:ŌĆ©ŌĆ©personal productivity management ŌĆ©from the perspective ...kiteracer

╠²

Introduction

Summary of the GTD method

Cognitive foundations of knowledge work

Cognitive paradigms applied to GTD

Further research about GTD (brainstorming)

Collaborative GTD

GTD and happiness.

Etc.cognitive-restructuring-for-self-growth.pptx

cognitive-restructuring-for-self-growth.pptxStrengthsTheatre

╠²

Regular practice of these cognitive restructuring techniques leads to a lasting, positive transformation of your mental landscape. For personality development classes, visit - sanjeevdatta.comVictim to Victory: A Survival Guide to Personal Injury

Victim to Victory: A Survival Guide to Personal Injurynewbrunswick1

╠²

"This book is a powerful resource for anyone who has been injured and seeks to understand their rights.

Whether itŌĆÖs a car crash caused by a drunk driver, a slip and fall at work, or any other unforeseen incident, anyone can suddenly find themselves needing to navigate the complex world of personal injury. Whether you've suffered a personal injury or simply want to be prepared, this book will equip you with the knowledge and confidence to face the unexpected. DonŌĆÖt wait until itŌĆÖs too lateŌĆöunderstand your rights and how to protect them now.

Your journey to understanding justice begins here."Developing-a-Positive-Mindset-for-Success

Developing-a-Positive-Mindset-for-Successoziasrondonc

╠²

A positive mindset is a powerful tool for achieving success in both personal and professional life. This presentation explores the psychology behind positive thinking, practical strategies to shift your mindset, and how cultivating resilience, gratitude, and self-discipline can help you overcome challenges and reach your goals. Learn how to reframe negative thoughts, develop confidence, and maintain motivation to create lasting success.Self_Development_Presentation.pptxdsfvndjsfvnjkdsfvnjdksfnvkjdsvndfsv

Self_Development_Presentation.pptxdsfvndjsfvnjkdsfvnjdksfnvkjdsvndfsvRakshitAwasthi1

╠²

dsfjnvkjsdfnvjksdnvjkdsfvnjdksfvBuilding-Emotional-Resilience-How-to-Handle-Lifes-Challenges

Building-Emotional-Resilience-How-to-Handle-Lifes-Challengesoziasrondonc

╠²

In this presentation, we explore the concept of emotional resilience and its vital role in handling lifeŌĆÖs challenges. Learn practical strategies for building emotional strength, coping with stress, and overcoming setbacks. Discover how resilience can improve mental health, boost well-being, and help you thrive in difficult situations. Perfect for anyone looking to develop a resilient mindset and approach life with confidence, regardless of the obstacles they face.Deductive-and-Inductive-Argument.. logic

- 1. Analysis of Statements/ Deductive and Inductive Arguments Mr. Zandro Jade Q. Albo Faculty, School of Arts and Sciences

- 2. You know that all sentences are grammatically classified into five main types. These are: 1. Interrogative sentence - When you ask a question like: What time is it? And alternatively, What is my grade in Philo I? You know that you are using an interrogative sentence. 2. Imperative sentence - when you issue commands like Shut the door! and, Put out the fire! You know you are using an imperative sentence. 3. Exclamatory sentence - when you are surprised and utter What a game! or, when you express pleasure and say This is good! You know you are using an exclamatory sentence. 4. Expletive sentence - But if you are daydreaming and you express a desire or a wish like: I hope my business succeed! or I hope to finish my PhD in philosophy! These are expletive sentences. 5. Declarative Sentence - Later

- 3. Let us quote from Wittgenstein again: But how many kinds of sentences are there? Say assertion, question, and command? --- There are countless kinds: countless different kinds of use of what we call symbols, words, and sentences. And the multiplicity is not something fixed, given once and for all, but new types of language, new language games, as we may say come into existence, and others become obsolete and get forgotten ŌĆ” the term language-game is meant to bring into prominence the fact that speaking of language is part of an activity, or a form of life.

- 4. Let us now focus our attention on one very important use of language, namely, using a sentence to assert a knowledge claim. The linguistic bearer of knowledge claims is often called a proposition or a statement in the current linguistic convention. Let us describe this language game. You know that interrogative, imperative, exclamatory and expletive sentences are merely uttered. We do not quarrel about their truth because they have no truth value. When you issue a command Shut the door! the command is neither true nor false; and even if the command is not obeyed, the command is not falsified. Similarly, when you exclaim What a game! you have not said anything true or false because you have not made a knowledge claim. These types of sentences have no truth-values because nothing was asserted and nothing was denied.

- 5. The case is quite different when you use a declarative sentence to assert of deny something in the world that can be either true of false. In this case, you have used a declarative sentence to assert a knowledge claim. And you know that the linguistic bearer of a knowledge claim is either the proposition or statement. This use of a declarative sentence to assert a knowledge claim is very important not only in Logic but in Epistemology as well. declarative sentence - is a statement of something Argument- where not talking about raising your voice and verbal battle with each other. A connected series of statements or reasons intended to establish a position or a conclusion.

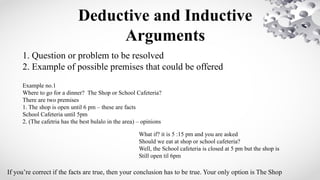

- 6. Deductive and Inductive Arguments 1. Question or problem to be resolved 2. Example of possible premises that could be offered Example no.1 Where to go for a dinner? The Shop or School Cafeteria? There are two premises 1. The shop is open until 6 pm ŌĆō these are facts School Cafeteria until 5pm 2. (The cafetria has the best bulalo in the area) ŌĆō opinions What if? it is 5 :15 pm and you are asked Should we eat at shop or school cafeteria? Well, the School cafeteria is closed at 5 pm but the shop is Still open til 6pm If youŌĆÖre correct if the facts are true, then your conclusion has to be true. Your only option is The Shop

- 7. AN ARGUMENT IN WHICH THE CONCLUSION NECESSARILY FOLLOWS THE PREMISES, IF THE PREMISES ARE TRUE, THEN THE CONCLUSION IS ALSO TRUE- THIS IS A DEDUCTIVE ARGUMENT.

- 8. What if the case is this it is only 4 pm Should we eat at the shop or school cafeteria? The shop is slightly ok? But the school cafeteria has the best bulalo food In this case the decision to go to school cafeteria cannot be true, the conclusion does not logically follow from the premises, you simply gave an option ŌĆ”

- 9. AN ARGUMENT IN WHICH THE ACCEPTANCE OF THE CONCLUSION DEPENDS ON THE STRENGTH OF THE PREMISES IN WHICH THE PREMISES DO NOT PROVE BUT MERELY SUPPORT THE CONCLUSION IS A INDUCTIVE ARGUMENT

- 10. Example no. 2 How many classes to take? Next semester There are two premises: 1. Twelve units is cost 8,000, fifteen is 8,700 pesos ŌĆō these are facts 2. (Taking more classes every semester will get you done faster) ŌĆōopinions

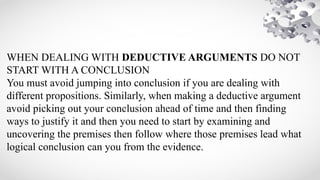

- 11. WHEN DEALING WITH DEDUCTIVE ARGUMENTS DO NOT START WITH A CONCLUSION You must avoid jumping into conclusion if you are dealing with different propositions. Similarly, when making a deductive argument avoid picking out your conclusion ahead of time and then finding ways to justify it and then you need to start by examining and uncovering the premises then follow where those premises lead what logical conclusion can you from the evidence.

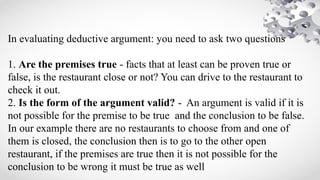

- 12. In evaluating deductive argument: you need to ask two questions 1. Are the premises true - facts that at least can be proven true or false, is the restaurant close or not? You can drive to the restaurant to check it out. 2. Is the form of the argument valid? - An argument is valid if it is not possible for the premise to be true and the conclusion to be false. In our example there are no restaurants to choose from and one of them is closed, the conclusion then is to go to the other open restaurant, if the premises are true then it is not possible for the conclusion to be wrong it must be true as well

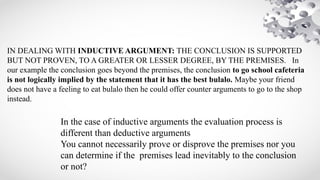

- 13. IN DEALING WITH INDUCTIVE ARGUMENT: THE CONCLUSION IS SUPPORTED BUT NOT PROVEN, TO A GREATER OR LESSER DEGREE, BY THE PREMISES. In our example the conclusion goes beyond the premises, the conclusion to go school cafeteria is not logically implied by the statement that it has the best bulalo. Maybe your friend does not have a feeling to eat bulalo then he could offer counter arguments to go to the shop instead. In the case of inductive arguments the evaluation process is different than deductive arguments You cannot necessarily prove or disprove the premises nor you can determine if the premises lead inevitably to the conclusion or not?

- 14. In evaluating inductive arguments you should ask the questions: 1. Are the premises true or at least acceptable?- You may find premises that are not necessarily assessed. Rather than facts you will often have matters of opinion. The assertion that the cafeteria is the best bulalo is a matter of opinion over which people may disagree. In this case consider if the premise is acceptable as reasonable. 2. Are the premises relevant to the issue at hand? Next is you need to decide whether that premise in this case the opinion that the cafeteria has the best bulalo is relevant.Is the premise related to the issue at hand? Here it does seem relevant to consider the reputation of the restaurant in deciding where to eat. However, if some says we should eat to cafeteria because there are chicks, you might question whether that reason is relevant to the issue at hand. 3. Is the premise sufficient to justify the conclusion? Is the opinion that the Cafeteria has the best bulalo really enough to base the decision on? Are there other things you might want to consider, you may ask. How long will it wait for the table? Or how good is the service?

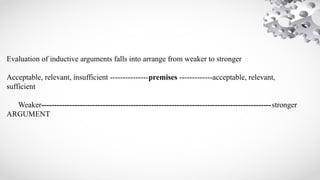

- 15. Evaluation of inductive arguments falls into arrange from weaker to stronger Acceptable, relevant, insufficient ---------------premises -------------acceptable, relevant, sufficient Weaker------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------stronger ARGUMENT