1 of 28

Downloaded 123 times

Recommended

06 random drift

06 random driftIndranil Bhattacharjee

Ã˝

Five factors drive evolution in populations: mutation, migration, genetic drift, natural selection, and nonrandom mating. Genetic drift is the change in allele frequencies that occurs due to random sampling error in small populations. It can cause alleles to be lost or fixed in a population by chance alone, independent of adaptive effects. The rate of genetic drift is influenced by population size, with smaller populations experiencing stronger drift effects due to increased sampling error. Effective population size is often much smaller than actual population size due to factors like unequal sex ratios. Genetic drift reduces genetic diversity over time and can cause maladaptive evolution if drift is stronger than selection.Epigenomics gyanika

Epigenomics gyanikagyanikashukla

Ã˝

The document discusses epigenetics and epigenomics in plants, describing the main epigenetic modifications including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs. It reviews several ongoing research projects applying epigenomics to improve crop traits and stress resistance in important crops like wheat, rice, and maize. Going forward, further research is needed to better understand how epigenetic changes influence plant development and physiology, their degree of heritability, and how epigenomics can be used to enhance crop breeding.Hardy weinberg supplement

Hardy weinberg supplementPratheep Sandrasaigaran

Ã˝

The slide discuss on briefly on the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and how does the Law of Population Genetics are accounted in a population.New Generation Sequencing Technologies: an overview

New Generation Sequencing Technologies: an overviewPaolo Dametto

Ã˝

The document provides a history of DNA sequencing technologies. It begins with the discovery of DNA's structure in 1953 and the development of recombinant DNA technology in the 1970s. First generation Sanger sequencing produced short reads over 1,000 years to sequence the human genome. Next generation sequencing (NGS) platforms since 2005 have dramatically reduced costs while increasing throughput. NGS methods like Roche/454 pyrosequencing, Illumina/Solexa sequencing by synthesis, SOLiD ligation sequencing, and single-molecule real-time sequencing by Pacific Biosciences now enable large-scale genome and transcriptome analysis.Forces changing gene frequency

Forces changing gene frequencySyedShaanz

Ã˝

This document discusses genetic processes that can change gene frequencies in populations. There are two main types:

1. Systematic processes like migration, mutation, and selection that tend to change gene frequencies predictably in amount and direction. They act in both large and small populations.

2. Dispersive processes that arise in small populations from random sampling effects. They are predictable in amount but not direction and only act in small populations. Random genetic drift is a main dispersive process.BIOL335: Genetic selection

BIOL335: Genetic selectionPaul Gardner

Ã˝

This document discusses various methods for measuring genetic selection in genomes. It examines comparing rates of synonymous and non-synonymous mutations to identify regions under negative or positive selection. Another method looks for extremely conserved elements or rapidly evolving regions across species. Analyzing population variation data through measures like Tajima's D or GWAS can also reveal selective sweeps. Transposon-free and INDEL-free regions may also indicate genetic selection.SNP Genotyping Technologies

SNP Genotyping TechnologiesSivamaniBalasubramaniam

Ã˝

Techniques of SNP Genotyping can be summarized as follows:

There are several techniques for genotyping SNPs including hybridization methods, enzyme-based methods, and other methods based on physical properties of DNA. Popular hybridization methods include DASH, molecular beacons, and gene chip arrays. Common enzyme-based techniques are RFLP, Invader assay, and oligonucleotide ligation assay. Other physical property-based methods include SSCP, TGGE, and pyrosequencing. Each method has its own pros and cons related to factors like speed, cost, and accuracy. Choosing the appropriate SNP genotyping technique depends on the number of SNPs needed to be analyzed and sample size.Snp genotyping

Snp genotypingshivendra kumar

Ã˝

This document summarizes Shivendra Kumar's class presentation on SNP genotyping using KASP. It introduces SNP genotyping and the KASP platform. It describes using KASP to genotype a wheat mapping population derived from a cross between an introgression line containing stripe rust resistance genes and a susceptible cultivar. KASP markers were developed and used to map the resistance genes. One candidate resistance gene was identified and further analyzed through expression studies and development of a linked KASP marker. Recombinants were identified and confirmed through additional KASP genotyping.Introduction to NGS Variant Calling Analysis (UEB-UAT Bioinformatics Course -...

Introduction to NGS Variant Calling Analysis (UEB-UAT Bioinformatics Course -...VHIR Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca

Ã˝

Course: Bioinformatics for Biomedical Research (2014).

Session: 2.3- Introduction to NGS Variant Calling Analysis.

Statistics and Bioinformatisc Unit (UEB) & High Technology Unit (UAT) from Vall d'Hebron Research Institute (www.vhir.org), Barcelona.Population genetics basic concepts

Population genetics basic concepts Meena Barupal

Ã˝

Population genetics is the study of genetic variation within species. The key concepts are:

1) The Hardy-Weinberg principle states that allele and genotype frequencies in a population will remain constant from generation to generation if mating is random and other evolutionary forces are absent.

2) Founder effects occur when new populations are established by a small number of individuals, resulting in a loss of genetic variation compared to the original population.

3) Factors like non-random mating, genetic drift, migration, mutation, and natural selection can cause changes in allele frequencies over time, known as microevolution.GWAS

GWASCheryl Miner

Ã˝

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) technology has been a primary method for identifying the genes responsible for diseases and other traits for the past ten years. GWAS continues to be highly relevant as a scientific method. Over 2,000 human GWAS reports now appear in scientific journals. Our free eBook aims to explain the basic steps and concepts to complete a GWAS experiment.Snapgene

SnapgeneManish Thakur

Ã˝

SnapGene is software that allows users to visualize and annotate DNA sequences. It can be used to plan cloning experiments and PCR strategies through features like restriction enzyme mapping and primer design. SnapGene provides customizable views of sequences and their annotations. It aims to help researchers fully document their molecular biology work to save time and money.Ngs introduction

Ngs introductionAlagar Suresh

Ã˝

This document discusses the history and evolution of DNA sequencing technologies. It begins with early manual sequencing methods developed in the 1970s by Sanger and others. Automated Sanger sequencing and the sequencing of larger genomes followed in the 1980s-1990s. Next generation sequencing (NGS) methods were developed starting in 1996 and became commercially available in 2005, enabling massively parallel sequencing. NGS platforms such as 454, Illumina, and SOLiD are discussed. Third generation real-time sequencing methods such as PacBio and nanopore sequencing are also introduced, providing longer read lengths. The document compares key parameters of different sequencing methods such as read length, accuracy, throughput, cost and advantages/disadvantages.Next generation sequencing technologies for crop improvement

Next generation sequencing technologies for crop improvementanjaligoud

Ã˝

different Next generation sequencing technologies from past to present and their utilisation for crop improvement programmesGenetic polymorphism

Genetic polymorphismClaude Nangwat

Ã˝

Genetic and environmental factors are the two keys that make human phenotype variations. When the genomic DNA sequences on equivalent chromosomes of any two individuals are compared, there is substantial variation in the sequence at many points throughout the genome. The term polymorphism was originally used to describe variations in shape and form that distinguish normal individuals within a species from each other. These days, geneticists use the term genetic polymorphisms to describe the inter-individual, functionally silent differences in DNA sequence that make each human genome unique. In order to better understand the phenomenon of genetic polymorphism, an emphasis has been laid on the structures and functions of nucleotides, genes and nucleic acids, including their relationship with polymorphism.

Polymorphism can be caused by factors such as mutation, which is defined as a permanent transmissible change in DNA sequence. Mutations are classified based on where they occur somatic and germ line mutations) and the length of the nucleotide sequences they affect (gene-level and chromosomal mutations). The various types of polymorphisms include; single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), small-scale insertions/deletions, polymorphic repetitive elements, microsatellite variation and haplotypes.

Variations in DNA sequences may have a major impact on how human beings respond to disease, bacteria, viruses, toxins, chemicals, drugs, and other therapies. Many clinical phenotypes observed in diseases seem to have considerable genetic components.

Determining genetic polymorphism can be based on morphological, biochemical, and molecular types of information. However, molecular markers have advantages over other kinds, where they show genetic differences on a more detailed level without interferences from environmental factors, and where they involve techniques that provide fast results detailing genetic diversity. Some of the techniques used in studying polymorphisms include; PCR based techniques and techniques involving DNA based markers.

Key words: Genetic polymorphism, effects in a population,

Next generation sequencing

Next generation sequencingTapish Goel

Ã˝

this presentation cover all the types of major sequencing platforms of past present and the ones which are recently developed and not tested much.NIDA FATIMA REAL TIME PCR PPT.pptx

NIDA FATIMA REAL TIME PCR PPT.pptxNidaFatima452469

Ã˝

Real-time PCR allows for the quantification of PCR products in real time during the amplification process. It involves the use of fluorescent dyes or probes that increase in fluorescence as more PCR products are generated. Common fluorescent dyes used include SYBR Green and various hydrolysis probes like TaqMan probes. Real-time PCR provides advantages over conventional PCR such as higher sensitivity, quantification capabilities, and automation. It has various applications including disease diagnosis, gene expression analysis, and SNP genotyping.Snp

SnpDr. sreeremya S

Ã˝

SNPs are found in

coding and (mostly) noncoding regions.

Occur with a very high frequency

about 1 in 1000 bases to 1 in 100 to 300 bases.

The abundance of SNPs and the ease with which they can be measured make these genetic variations significant.

SNPs close to particular gene acts as a marker for that gene.

SNPs in coding regions may alter the protein structure made by that coding region.

A SNP is defined as a single base change in a DNA sequence that occurs in a significant proportion (more than 1 percent) of a large population. Sequence genomes of a large number of people

Compare the base sequences to discover SNPs.

Generate a single map of the human genome containing all possible SNPs => SNP maps

Sequence based Markers

Sequence based Markerssukruthaa

Ã˝

The document discusses various DNA and RNA sequencing methods and technologies. It begins with an overview of sequencing-based markers like DNA sequencing, RNA sequencing, SNPs, epigenetic markers, and omics. The document then provides more details on the history and development of sequencing technologies, including early methods like Sanger and Maxam-Gilbert sequencing. It discusses next generation sequencing platforms like MPSS, 454 pyrosequencing, Illumina, Ion Torrent, ABI-SOLiD, and their approaches. The document concludes with an overview of third generation long-read sequencing technologies like SMRT and nanopore sequencing.2016. daisuke tsugama. next generation sequencing (ngs) for plant research

2016. daisuke tsugama. next generation sequencing (ngs) for plant researchFOODCROPS

Ã˝

This document provides an overview of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for plant research. It discusses the main NGS platforms, data analysis procedures including assembly, mapping, and applications such as RNA-seq, genome sequencing, RAD-seq, MutMap, and QTL-seq. The document aims to explain what NGS is, typical analysis workflows, and how NGS can be applied to questions in plant research.Epi519 Gwas Talk

Epi519 Gwas Talkjoshbis

Ã˝

A lecture for UW EPI 519 providing background for genome-wide association studies, a few examples of recent papers in the CVD GWAS literature, and some lessons and new directions. The talk was originally given in 2008 (in collaboration with a colleagure), this version has been updated slightly for 2010 and includes references for further reading.

Some of the typefaces may have been mangled on conversion; the file download should be more reliable. Protein characterization

Protein characterization Creative BioMart

Ã˝

Creative BioMart has more than 20 years of experience in protein characterization. We have extensive experience in developing and establishing protein identification methods to help our customers generate the data they need to obtain the level of product identification required for regulatory submission. These characterization services are also part of our stability and product launch support services, where we provide critical identity, purity, and performance measurements.

Introduction to NGS

Introduction to NGScursoNGS

Ã˝

NGS has enabled high-throughput genome sequencing and analysis, changing genomic research. Technologies like Roche 454, Solexa/Illumina, and SOLiD allow massively parallel sequencing of genomes. NGS has applications in de novo genome sequencing, resequencing, RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, methylation analysis, and more. It provides advantages over microarrays like detecting novel transcripts, splicing variants, and sequence variations. NGS data requires processing including quality control, mapping, and variant identification to realize its full potential to revolutionize genomic research and medicine.A Journey Through The History Of DNA Sequencing

A Journey Through The History Of DNA Sequencing Eurofins Genomics Germany GmbH

Ã˝

The history of DNA sequencing. Let’s take a journey from the first isolation of DNA to next generation sequencing (NGS). Read more.Ftt1033 7 population genetics-2013

Ftt1033 7 population genetics-2013Rione Drevale

Ã˝

Here are the solutions to the try these problems:

1. a) T allele frequency = (88/125) + (1/2)*(37/125) = 0.72

t allele frequency = 1 - 0.72 = 0.28

b) TT genotype frequency = 0.72^2 = 0.52

Tt genotype frequency = 2*0.72*0.28 = 0.48

tt genotype frequency = 0.28^2 = 0.08

2. p = 200/300 = 0.667

q = 1 - p = 0.333

3. a) Recessive allele frequency = ‚àö(1/2500) = 0.02

bComparative Genomic Hybridization

Comparative Genomic HybridizationAhmed Ghobashi

Ã˝

Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) is a molecular cytogenetic technique that compares the DNA of a test sample to a reference sample to detect copy number variations without cell culturing. It involves labelling the tumor and normal DNA with different fluorescent dyes, mixing them, and hybridizing them to normal chromosomes to detect losses or gains of genetic material in the tumor DNA through fluorescence ratios. While CGH can detect events over 10-20 Mb, array CGH uses genomic fragments as targets and can detect changes as small as 5-10 kb, making it a faster and more sensitive technique. Array CGH is commonly used in cancer research and diagnosis of genetic disorders.Ngs ppt

Ngs pptArcha Dave

Ã˝

This document provides an overview of next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. It discusses the history and evolution of DNA sequencing, from early manual methods developed by Sanger to modern high-throughput NGS approaches. Key NGS methods described include Illumina sequencing by synthesis, Ion Torrent semiconductor sequencing, 454 pyrosequencing, and SOLiD ligation sequencing. Compared to Sanger, NGS allows massively parallel sequencing of many samples at lower cost and higher throughput. While NGS has advanced biological research, each method still has advantages and limitations related to read length, accuracy, and cost.More Related Content

What's hot (20)

Introduction to NGS Variant Calling Analysis (UEB-UAT Bioinformatics Course -...

Introduction to NGS Variant Calling Analysis (UEB-UAT Bioinformatics Course -...VHIR Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca

Ã˝

Course: Bioinformatics for Biomedical Research (2014).

Session: 2.3- Introduction to NGS Variant Calling Analysis.

Statistics and Bioinformatisc Unit (UEB) & High Technology Unit (UAT) from Vall d'Hebron Research Institute (www.vhir.org), Barcelona.Population genetics basic concepts

Population genetics basic concepts Meena Barupal

Ã˝

Population genetics is the study of genetic variation within species. The key concepts are:

1) The Hardy-Weinberg principle states that allele and genotype frequencies in a population will remain constant from generation to generation if mating is random and other evolutionary forces are absent.

2) Founder effects occur when new populations are established by a small number of individuals, resulting in a loss of genetic variation compared to the original population.

3) Factors like non-random mating, genetic drift, migration, mutation, and natural selection can cause changes in allele frequencies over time, known as microevolution.GWAS

GWASCheryl Miner

Ã˝

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) technology has been a primary method for identifying the genes responsible for diseases and other traits for the past ten years. GWAS continues to be highly relevant as a scientific method. Over 2,000 human GWAS reports now appear in scientific journals. Our free eBook aims to explain the basic steps and concepts to complete a GWAS experiment.Snapgene

SnapgeneManish Thakur

Ã˝

SnapGene is software that allows users to visualize and annotate DNA sequences. It can be used to plan cloning experiments and PCR strategies through features like restriction enzyme mapping and primer design. SnapGene provides customizable views of sequences and their annotations. It aims to help researchers fully document their molecular biology work to save time and money.Ngs introduction

Ngs introductionAlagar Suresh

Ã˝

This document discusses the history and evolution of DNA sequencing technologies. It begins with early manual sequencing methods developed in the 1970s by Sanger and others. Automated Sanger sequencing and the sequencing of larger genomes followed in the 1980s-1990s. Next generation sequencing (NGS) methods were developed starting in 1996 and became commercially available in 2005, enabling massively parallel sequencing. NGS platforms such as 454, Illumina, and SOLiD are discussed. Third generation real-time sequencing methods such as PacBio and nanopore sequencing are also introduced, providing longer read lengths. The document compares key parameters of different sequencing methods such as read length, accuracy, throughput, cost and advantages/disadvantages.Next generation sequencing technologies for crop improvement

Next generation sequencing technologies for crop improvementanjaligoud

Ã˝

different Next generation sequencing technologies from past to present and their utilisation for crop improvement programmesGenetic polymorphism

Genetic polymorphismClaude Nangwat

Ã˝

Genetic and environmental factors are the two keys that make human phenotype variations. When the genomic DNA sequences on equivalent chromosomes of any two individuals are compared, there is substantial variation in the sequence at many points throughout the genome. The term polymorphism was originally used to describe variations in shape and form that distinguish normal individuals within a species from each other. These days, geneticists use the term genetic polymorphisms to describe the inter-individual, functionally silent differences in DNA sequence that make each human genome unique. In order to better understand the phenomenon of genetic polymorphism, an emphasis has been laid on the structures and functions of nucleotides, genes and nucleic acids, including their relationship with polymorphism.

Polymorphism can be caused by factors such as mutation, which is defined as a permanent transmissible change in DNA sequence. Mutations are classified based on where they occur somatic and germ line mutations) and the length of the nucleotide sequences they affect (gene-level and chromosomal mutations). The various types of polymorphisms include; single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), small-scale insertions/deletions, polymorphic repetitive elements, microsatellite variation and haplotypes.

Variations in DNA sequences may have a major impact on how human beings respond to disease, bacteria, viruses, toxins, chemicals, drugs, and other therapies. Many clinical phenotypes observed in diseases seem to have considerable genetic components.

Determining genetic polymorphism can be based on morphological, biochemical, and molecular types of information. However, molecular markers have advantages over other kinds, where they show genetic differences on a more detailed level without interferences from environmental factors, and where they involve techniques that provide fast results detailing genetic diversity. Some of the techniques used in studying polymorphisms include; PCR based techniques and techniques involving DNA based markers.

Key words: Genetic polymorphism, effects in a population,

Next generation sequencing

Next generation sequencingTapish Goel

Ã˝

this presentation cover all the types of major sequencing platforms of past present and the ones which are recently developed and not tested much.NIDA FATIMA REAL TIME PCR PPT.pptx

NIDA FATIMA REAL TIME PCR PPT.pptxNidaFatima452469

Ã˝

Real-time PCR allows for the quantification of PCR products in real time during the amplification process. It involves the use of fluorescent dyes or probes that increase in fluorescence as more PCR products are generated. Common fluorescent dyes used include SYBR Green and various hydrolysis probes like TaqMan probes. Real-time PCR provides advantages over conventional PCR such as higher sensitivity, quantification capabilities, and automation. It has various applications including disease diagnosis, gene expression analysis, and SNP genotyping.Snp

SnpDr. sreeremya S

Ã˝

SNPs are found in

coding and (mostly) noncoding regions.

Occur with a very high frequency

about 1 in 1000 bases to 1 in 100 to 300 bases.

The abundance of SNPs and the ease with which they can be measured make these genetic variations significant.

SNPs close to particular gene acts as a marker for that gene.

SNPs in coding regions may alter the protein structure made by that coding region.

A SNP is defined as a single base change in a DNA sequence that occurs in a significant proportion (more than 1 percent) of a large population. Sequence genomes of a large number of people

Compare the base sequences to discover SNPs.

Generate a single map of the human genome containing all possible SNPs => SNP maps

Sequence based Markers

Sequence based Markerssukruthaa

Ã˝

The document discusses various DNA and RNA sequencing methods and technologies. It begins with an overview of sequencing-based markers like DNA sequencing, RNA sequencing, SNPs, epigenetic markers, and omics. The document then provides more details on the history and development of sequencing technologies, including early methods like Sanger and Maxam-Gilbert sequencing. It discusses next generation sequencing platforms like MPSS, 454 pyrosequencing, Illumina, Ion Torrent, ABI-SOLiD, and their approaches. The document concludes with an overview of third generation long-read sequencing technologies like SMRT and nanopore sequencing.2016. daisuke tsugama. next generation sequencing (ngs) for plant research

2016. daisuke tsugama. next generation sequencing (ngs) for plant researchFOODCROPS

Ã˝

This document provides an overview of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for plant research. It discusses the main NGS platforms, data analysis procedures including assembly, mapping, and applications such as RNA-seq, genome sequencing, RAD-seq, MutMap, and QTL-seq. The document aims to explain what NGS is, typical analysis workflows, and how NGS can be applied to questions in plant research.Epi519 Gwas Talk

Epi519 Gwas Talkjoshbis

Ã˝

A lecture for UW EPI 519 providing background for genome-wide association studies, a few examples of recent papers in the CVD GWAS literature, and some lessons and new directions. The talk was originally given in 2008 (in collaboration with a colleagure), this version has been updated slightly for 2010 and includes references for further reading.

Some of the typefaces may have been mangled on conversion; the file download should be more reliable. Protein characterization

Protein characterization Creative BioMart

Ã˝

Creative BioMart has more than 20 years of experience in protein characterization. We have extensive experience in developing and establishing protein identification methods to help our customers generate the data they need to obtain the level of product identification required for regulatory submission. These characterization services are also part of our stability and product launch support services, where we provide critical identity, purity, and performance measurements.

Introduction to NGS

Introduction to NGScursoNGS

Ã˝

NGS has enabled high-throughput genome sequencing and analysis, changing genomic research. Technologies like Roche 454, Solexa/Illumina, and SOLiD allow massively parallel sequencing of genomes. NGS has applications in de novo genome sequencing, resequencing, RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, methylation analysis, and more. It provides advantages over microarrays like detecting novel transcripts, splicing variants, and sequence variations. NGS data requires processing including quality control, mapping, and variant identification to realize its full potential to revolutionize genomic research and medicine.A Journey Through The History Of DNA Sequencing

A Journey Through The History Of DNA Sequencing Eurofins Genomics Germany GmbH

Ã˝

The history of DNA sequencing. Let’s take a journey from the first isolation of DNA to next generation sequencing (NGS). Read more.Ftt1033 7 population genetics-2013

Ftt1033 7 population genetics-2013Rione Drevale

Ã˝

Here are the solutions to the try these problems:

1. a) T allele frequency = (88/125) + (1/2)*(37/125) = 0.72

t allele frequency = 1 - 0.72 = 0.28

b) TT genotype frequency = 0.72^2 = 0.52

Tt genotype frequency = 2*0.72*0.28 = 0.48

tt genotype frequency = 0.28^2 = 0.08

2. p = 200/300 = 0.667

q = 1 - p = 0.333

3. a) Recessive allele frequency = ‚àö(1/2500) = 0.02

bComparative Genomic Hybridization

Comparative Genomic HybridizationAhmed Ghobashi

Ã˝

Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) is a molecular cytogenetic technique that compares the DNA of a test sample to a reference sample to detect copy number variations without cell culturing. It involves labelling the tumor and normal DNA with different fluorescent dyes, mixing them, and hybridizing them to normal chromosomes to detect losses or gains of genetic material in the tumor DNA through fluorescence ratios. While CGH can detect events over 10-20 Mb, array CGH uses genomic fragments as targets and can detect changes as small as 5-10 kb, making it a faster and more sensitive technique. Array CGH is commonly used in cancer research and diagnosis of genetic disorders.Ngs ppt

Ngs pptArcha Dave

Ã˝

This document provides an overview of next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. It discusses the history and evolution of DNA sequencing, from early manual methods developed by Sanger to modern high-throughput NGS approaches. Key NGS methods described include Illumina sequencing by synthesis, Ion Torrent semiconductor sequencing, 454 pyrosequencing, and SOLiD ligation sequencing. Compared to Sanger, NGS allows massively parallel sequencing of many samples at lower cost and higher throughput. While NGS has advanced biological research, each method still has advantages and limitations related to read length, accuracy, and cost.Introduction to NGS Variant Calling Analysis (UEB-UAT Bioinformatics Course -...

Introduction to NGS Variant Calling Analysis (UEB-UAT Bioinformatics Course -...VHIR Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca

Ã˝

Viewers also liked (17)

Barbujani abt lecture

Barbujani abt lectureGenetica, Ferrara University, Italy

Ã˝

A summary of human evolutionary studies dealing with the failure of racial classificationLisbon genome diversity

Lisbon genome diversityGenetica, Ferrara University, Italy

Ã˝

1. The human genome is very similar to the chimpanzee genome, with individual genetic diversity among humans being the lowest of all primates.

2. While population differences among humans are also relatively low, genetic studies show inconsistent clustering of genotypes across genes and loci.

3. Models of human migration out of Africa best explain observed genetic patterns, with gradients of diversity correlated with distance from Africa.Barbujani leicester

Barbujani leicesterGenetica, Ferrara University, Italy

Ã˝

1. The document discusses three main questions regarding human evolutionary genetics: the debate between hybridization models vs. the Southern dispersal route out of Africa, the coevolution of cultural and biological diversity, and challenges to the persistence of racial paradigms given genomic data.

2. Regarding the first question, the author notes several problems with hybridization hypotheses and presents evidence supporting an earlier dispersal of modern humans out of Africa via a Southern route, avoiding contact with Neanderthals.

3. For the second question, the author reviews evidence that increases in brain size did not necessarily correlate with genes associated with cognitive functions, and that cultural and linguistic changes likely evolved in parallel with biological changes.

4.Genpop10coal e abc

Genpop10coal e abcGenetica, Ferrara University, Italy

Ã˝

Introduction to coalescent theory and Approximate bayesian Computation (ABC)Human genetic diversity. ESHG Barcelona

Human genetic diversity. ESHG BarcelonaGenetica, Ferrara University, Italy

Ã˝

This document summarizes research on human genetic population structure and diversity. The key points are:

- 85% of human genetic variation exists within populations, 10% among continental groups, and 5% among populations within the same continent.

- Clustering analyses of genetic data yield inconsistent groupings depending on the traits or markers used, and populations form a continuous gradient without clear boundaries.

- The patterns of genetic diversity are consistent with an origin of modern humans in Africa followed by serial founder effects during dispersal, around 56,000 years ago.Comparing genes across linguistic families

Comparing genes across linguistic familiesGenetica, Ferrara University, Italy

Ã˝

1. The document compares genetic and linguistic diversity in Europe and finds some correlations between the two.

2. Structural features of languages may provide a better basis for comparison than vocabulary. Principal component analysis of genetic and linguistic data show some similarities in clustering.

3. Recent population mixing can account for some inconsistencies between the genetic and linguistic patterns. Overall, geography, genetics, and language are interrelated but influenced by separate evolutionary processes over long time periods.Similar to Gen pop4ld (20)

More from Genetica, Ferrara University, Italy (15)

08 genomica

08 genomicaGenetica, Ferrara University, Italy

Ã˝

Outline of methods for genomic analysis - Human genome diversityPerché non possiamo non dirci africani. Otto cose da ricordare sulla biodiver...

Perché non possiamo non dirci africani. Otto cose da ricordare sulla biodiver...Genetica, Ferrara University, Italy

Ã˝

Perché alle Olimpiadi le gare di sprint le vincono sempre atleti caraibici, le maratone gli africani dell'est, che però nel nuoto non combinano niente? Non sarà che ci sono differenze razziali? La risposta, ancora una volta, è no.Perché non possiamo non dirci africani. Otto cose da ricordare sulla biodiver...

Perché non possiamo non dirci africani. Otto cose da ricordare sulla biodiver...Genetica, Ferrara University, Italy

Ã˝

Gen pop4ld

- 1. Genetica di popolazioni 4: Linkage disequilibrium

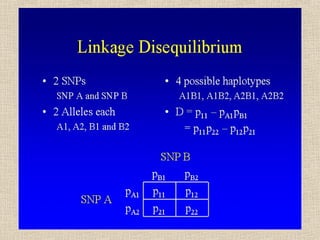

- 2. Programma del corso 1. Diversità genetica 2. Equilibrio di Hardy-Weinberg 3. Inbreeding 4. Linkage disequilibrium 5. Mutazione 6. Deriva genetica 7. Flusso genico e varianze genetiche 8. Selezione 9. Mantenimento dei polimorfismi e teoria neutrale 10. Introduzione alla teoria coalescente 11. Struttura e storia della popolazione umana + Lettura critica di articoli

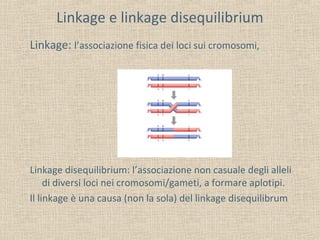

- 3. Linkage e linkage disequilibrium Linkage: l’associazione fisica dei loci sui cromosomi, Linkage disequilibrium: l’associazione non casuale degli alleli di diversi loci nei cromosomi/gameti, a formare aplotipi. Il linkage è una causa (non la sola) del linkage disequilibrum

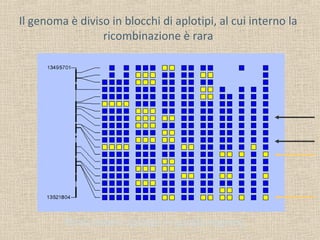

- 5. Il genoma è diviso in blocchi di aplotipi, al cui interno la ricombinazione è rara Nove diversi aplotipi in questa regione

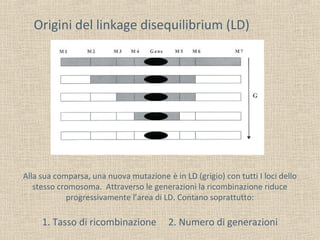

- 6. Origini del linkage disequilibrium (LD) Alla sua comparsa, una nuova mutazione è in LD (grigio) con tutti I loci dello stesso cromosoma. Attraverso le generazioni la ricombinazione riduce progressivamente l’area di LD. Contano soprattutto: 1. Tasso di ricombinazione 2. Numero di generazioni

- 7. Quindi: Equilibrio di Hardy-Weinberg e linkage disequilibrium • Basta una generazione di accoppiamento casuale per raggiungere l’equilibrio di HW a un locus • Se si studiano più loci, possono essere necessarie parecchie generazioni perché si raggiunga anche un linkage equilibrium, cioé perché gli alleli siano associati casualmente nei gameti

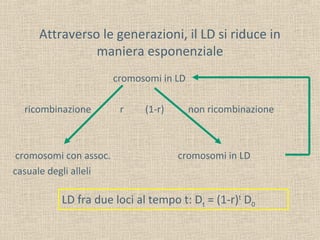

- 8. Attraverso le generazioni, il LD si riduce in maniera esponenziale cromosomi in LD ricombinazione cromosomi con assoc. casuale degli alleli r (1-r) non ricombinazione cromosomi in LD LD fra due loci al tempo t: Dt = (1-r)t D0

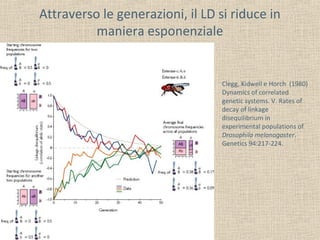

- 9. Attraverso le generazioni, il LD si riduce in maniera esponenziale Clegg, Kidwell e Horch (1980) Dynamics of correlated genetic systems. V. Rates of decay of linkage disequilibrium in experimental populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 94:217-224.

- 10. Vediamo se ci siamo capiti Perché il LD declina più rapidamente del previsto? Perché nell’esperimento indicato dalla linea blu alla fine si ottiene un LD opposto a quello di partenza?

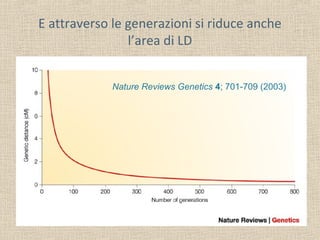

- 11. E attraverso le generazioni si riduce anche l’area di LD Nature Reviews Genetics 4; 701-709 (2003)

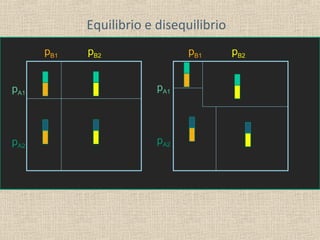

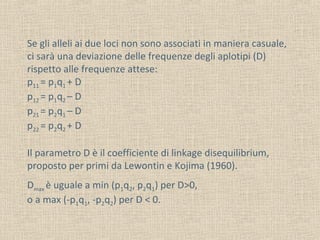

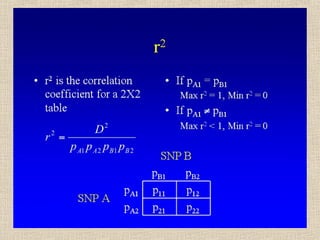

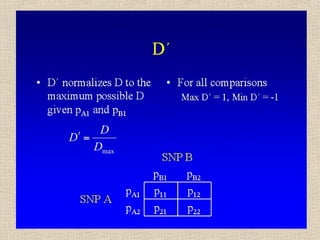

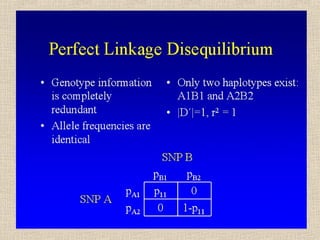

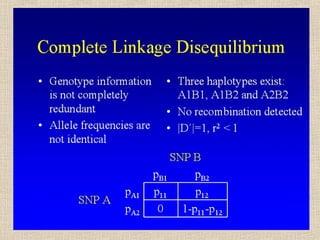

- 12. Se gli alleli ai due loci non sono associati in maniera casuale, ci sarà una deviazione delle frequenze degli aplotipi (D) rispetto alle frequenze attese: p11 = p1q1 + D p12 = p1q2 – D p21 = p2q1 – D p22 = p2q2 + D Il parametro D è il coefficiente di linkage disequilibrium, proposto per primi da Lewontin e Kojima (1960). Dmax è uguale a min (p1q2, p2q1) per D>0, o a max (-p1q1, -p2q2) per D < 0.

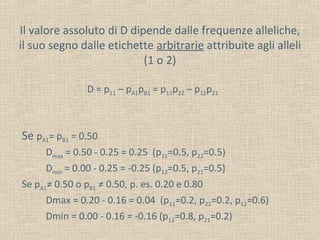

- 14. Il valore assoluto di D dipende dalle frequenze alleliche, il suo segno dalle etichette arbitrarie attribuite agli alleli (1 o 2) D = p11 – pA1pB1 = p11p22 – p12p21 Se pA1= pB1 = 0.50 Dmax = 0.50 - 0.25 = 0.25 (p11=0.5, p22=0.5) Dmin = 0.00 - 0.25 = -0.25 (p12=0.5, p21=0.5) Se pA1≠ 0.50 o pB1 ≠ 0.50, p. es. 0.20 e 0.80 Dmax = 0.20 - 0.16 = 0.04 (p11=0.2, p22=0.2, p12=0.6) Dmin = 0.00 - 0.16 = -0.16 (p12=0.8, p21=0.2)

- 19. Un sito web che calcola LD http://www.evotutor.org/EvoGen/EG4A.html

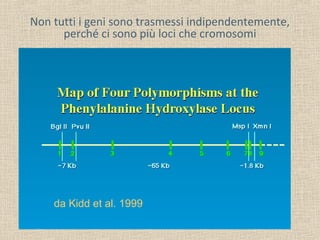

- 20. Non tutti i geni sono trasmessi indipendentemente, perché ci sono più loci che cromosomi da Kidd et al. 1999

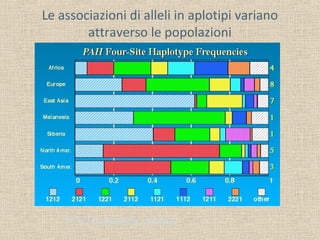

- 21. Le associazioni di alleli in aplotipi variano attraverso le popolazioni 24 = 16 possibili aplotipi

- 22. I livelli di linkage disequilibrium variano attraverso le popolazioni

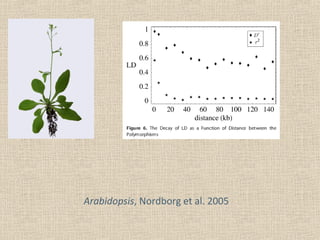

- 23. Arabidopsis, Nordborg et al. 2005

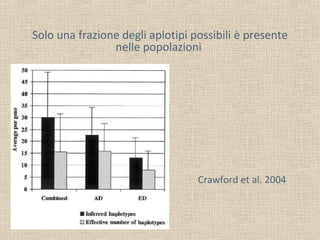

- 24. Solo una frazione degli aplotipi possibili è presente nelle popolazioni Crawford et al. 2004

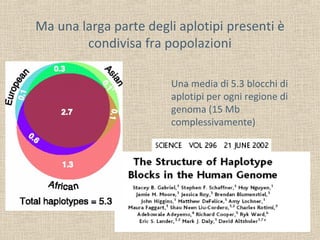

- 25. Ma una larga parte degli aplotipi presenti è condivisa fra popolazioni Una media di 5.3 blocchi di aplotipi per ogni regione di genoma (15 Mb complessivamente)

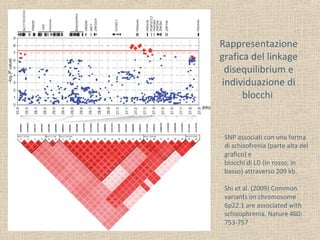

- 26. Rappresentazione grafica del linkage disequilibrium e individuazione di blocchi SNP associati con una forma di schizofrenia (parte alta del grafico) e blocchi di LD (in rosso, in basso) attraverso 209 kb. Shi et al. (2009) Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature 460: 753-757

- 27. Una review non recentissima, ma ancora buona

- 28. Sintesi • Due loci sono in linkage equilibrium se le frequenze genotipiche a un locus sono indipendenti da quelle all’altro locus • Il linkage disequilibrium è causato dalla mutazione e ridotto dalla ricombinazione • Basta una generazione di accoppiamento casuale per raggiungere l’equilibrio di Hardy-Weinberg, ma non il LD • Si misura il LD confrontando frequenze genotipiche osservate e attese a due loci, tramite le statistiche r, D e D’